Dante Gabriel Rossetti

VOL. I.

Â

Â

Â

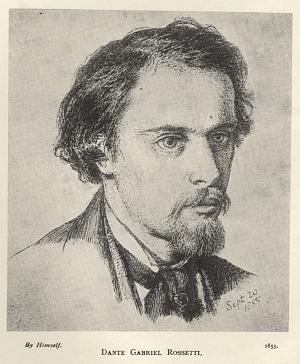

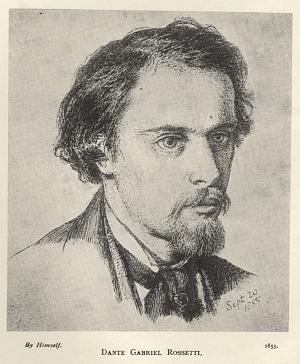

By Himself. 1855.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Figure: Self-portrait. Three-quarter view, head and shoulders, facing

right. Date in lower right corner, Sept 20, 1855.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

HIS FAMILY-LETTERS

WITH A MEMOIR

BY

WILLIAM MICHAEL ROSSETTI

VOL I.

AMS PRESS

NEW YORK

Note: The call number is written in pencil at the top of the page.

Â

Reprinted from the edition of 1895, London

First AMS EDITION published 1970

Manufactured in the United States of America

International Standard Book Number:

Complete Set: 0â404â05434âX

Volume 1: 0â404â05435â8

Library of Congress Number: 70â130231

AMS PRESS INC.

New York, N.Y. 10003

Â

DEDICATED TO

MY FOUR CHILDREN

WITH A FATHER'S HOPE

THAT RELATIVES OF

DANTE AND CHRISTINA ROSSETTI

AND DESCENDANTS OF

GABRIELE AND FRANCES ROSSETTI

WILL UPHOLD THE CREDIT OF

THEIR PATRONYMIC..

Â

In his

Recollections of Dante Gabriel

Rossetti

(1882) Mr. Hall Caine has informed us: âIt was always known to be

Rossetti's wish that, if at any moment after his death it should appear

that the story of his life required to be written, the one friend who,

during many of his later years, knew him most intimately, and to whom he

unlocked the most sacred secrets of his heart, Mr. Theodore Watts,

should write it, unless indeed it were undertaken by his brother

William.â

Dante Rossetti died on 9 April 1882; and after the lapse of a few months I

decided to put his Family-Letters into shape for early publication. Mr. Watts

acquiesced in the wish which I then entertained, and which I should still

entertain, that he, rather than myself, should be the biographer, writing a

Memoir to accompany the Letters. Doubtless he saw reason for not producing his

Memoir so soon as I had been expecting it; therefore, after a rather long

interval of years, I resolved in July 1894 that the Letters must now come out,

and, as they could not be unlinked with a Memoir, that I myself would write it.

The result is before the reader. If he would have preferred a Memoir from Mr.

Watts, I sympathize with him, but the option had ceased to be mine. There are

several reasons why a brother neither is nor can be the best biographer. Feeling

this, I had always intended

not to write a Life of Dante Rossetti. But circumstances have

proved too strong for me, and I submit to their dictate.

Had the book been published towards 1883, the Letters would have extended

very little beyond those addressed to my Mother and to myself. There were then

also a couple to my Father, and a very few to my Sister Christina. I am now

enabled to add some to my Grandfather Gaetano Polidori, my Uncle Henry Francis

Polydore, my Aunt Charlotte, Lydia Polidori, and my Wife Lucy Madox Rossetti;

also some others to Christina which, as they contain expressions of approval

with regard to her writings, she had herself with-held. No letters to other

members of the family appear to be in existence, though several must have been

written.

The technical arrangement of the printed correspondence can easily be

understood. The letters are all thrown into a single sequence, according to the

order of date: they are lettered from A to H, for the persons respectively

addressed, and each sub-division is progressively numbered within its own

limits. In every case where a letter seems to require any explanatory note or

observation, I have supplied this in a few preliminary words. The dates, when

not written by my brother himself, were in most cases jotted down at the time by

the recipient: in a few instances, where this was omitted, the dates now given

are approximate. Addresses are also frequently inserted in like manner. I have

preserved (and must ask the reader to pardon my mentioning so minute a point)

one instance of each form of subscribed name; and have also reproduced the name

in other cases where it seems more apposite to do so. In contrary instances I

omit both the name and the words of subscription which precede it. Some other

Family-Letters exist, addressed to the same

persons; but these are such as even a brother cannot

suppose to be of any public interest. From those here collected some passages

are omitted which, on one ground or another, are considered to be unsuited for

printing; but on the whole I have been sparing of excisions. Of the items

admitted, several are indeed short and scrappy; I have not however included

anything which appears to me to be entirely uninteresting to persons interested

in Dante Rossetti. Some letters, otherwise slight, fix the date of a picture or

poem; others show some trait of character, or contain some pointed or diverting

expression.

The letters, such as they are, shall be left to speak mainly for

themselves. Their language is constantly unadorned, often colloquial; the tone

of mind in them, concentrated; the feeling, while solid and sincere, uneffusive.

Their subject-matter is very generally personal to the writer, without

discursiveness of outlook, or eloquent or picturesque description; yet the

spirit is not egotistical or self-assertive. If I am wrong in these opinions,

the reader will decide the point for himself.

My brother was a rapid letter-writer, and on occasion a very prompt one,

but not negligent or haphazard. He always wrote to the point, without

amplification, or any effort after the major or minor graces of diction or

rhetoric. Multitudes of his letters must still presumably be extant in private

hands: a representative collection of them might be found to confirm the

impression which I should like to ensue from the present seriesâthat

as a correspondent he was straight-forward, pleasant, and noticeably free from

any calculated self-display. âDisinvoltoâ would be the Italian word.

Some persons may approve, others will disapprove, of the publication of

these Family-Letters. I print them because the doing so commends itself to my

own mind. At a very

childish age I was familiar with the old apologue of

the Man and his Son and the Donkey: it impressed me as equally true and

practical. I have always been conscious that opinions will be as numerous as

readers, and prefer to suit the opinions of those who happen to agree with

myself.

Recently I have had a painful reason for realizing to myself a very

pleasurable factâthat of the high estimation in which my brother,

himself no less than his work, is now publicly held, some thirteen years after

he passed away. The death of my beloved sister Christina, on 29 December 1894,

called forth a flood of not undeserved but assuredly very fervent praise; and in

the eulogies of her were intermixed many warm tributes to my

brotherâI might say, without a dissentient voice.

As regards my Memoir, I, having large knowledge and numerous materials,

have not consulted a single person except Christina, who, during the earlier

weeks of my undertaking, gave me orally the benefit of many reminiscences

relating chiefly to years of childhood, and often kept me right upon details as

to which I should have stumbled. On her bed of pain and rapidly approaching

death she preserved a singularly clear recollection of olden facts, and was

cheered in going over them with me.

Some readers of the Memoir may be inclined to ask meâ

âHave you told everything, of a substantial kind, that you know about

your deceased brother?ââMy answer shall be given

beforehand, and without disguise: âNo; I have told what I choose to

tell, and have left untold what I do not choose to tell; if you want more, be

pleased to consult some other informant.â

One word in conclusion. In case the present book should find favour with

the public, I should be disposed to rummage

among my ample stock of materials, and produce a

number of details relating not only to my brother, but also to other members or

connexions of the family. But at the age of sixty-five a man finds the horizon

of his work narrowed, and rapidly narrowing; and possibly this will not be.

St. Edmund's Terrace, London.

April 1895.

Â

-

I.

BIRTH.

Dante Rossetti's birth in London, 1828âHis

Godfathers. . . 3

-

II.

PARENTAGE.

Gabriele (Father of Dante) RossettiâHis birth in

VastoâHis Parents and BrothersâHis drawings,

studies, and writings, in Italyâ His political lyrics and

exileâMalta and John Hookham Frereâ Life in

LondonâHis deathâHis character, opinions, person,

etc.â His writings in England on Dante,

etc.âCarducci's opinion of his poetryâThe

centenary of his birth, VastoâDescriptions of him by Bell

Scott and Frederic StephensâMrs. Gabriele Rossetti, her life,

character, and personâSome versicles of hers. . . 3

-

III.

RELATIVES.

Dante Rossetti's Great-grandfathersâHis maternal

Grandfather, Gaetano Polidori, Secretary to Alfieri, and Italian teacher

in Londonâ Anecdotes of the French Revolution and of

AlfieriâPolidori's person, character, and

writingsâMrs. PolidoriâHer Father, William

PierceâConnexions of the Pierce family, Mrs. Bray,

etc.âMrs. Polidori's closing

yearsâHer sister and childrenâ Dr. John William

Polidori and his writingsâTeodorico

Pietrocola-RossettiâExtinction of the Rossetti family in

Vastoâ Instances of longevity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . 24

-

IV.

CHILDHOOD.

The four children of Gabriele RossettiâHouses in

Charlotte Streetâ Dante Rossetti and his Sister

MariaâWalks about London, etc.â Pet

animalsâSights and entertainments in

LondonâSinging, card-playing, illness, etc.âFirst

attempt at drawing, and resolve to be a painterâTheatrical

and other prints. . . . . . . . . . 36

-

V.

ACQUAINTANCES IN CHILDHOOD.

The Potters and other British friendsâNumerous

Italian friends of Gabriele RossettiâPistrucci, Sangiovanni,

etc.âProtestantizing ItaliansâMazzini and

PanizziâTalks on politicsâJohn Stuart Mill on

Continental and English Life . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

-

VI.

CHILDISH BOOK-READING AND SCRIBBLING.

Dante Rossetti's early trainingâThe Bible, Shakespear, Göthe, Walter Scott,

etc.âChildish drawings from

Henry VI.âRossetti's opinion of Scott's novels,

1871âBooks of prints and the National Gallery

âDante's poems read later onâChildish drama,

The Slave

, etc.â Childish drawingsâDante Rossetti

fortunate in his family surroundings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . 57

-

VII.

SCHOOL.

Dante Rossetti's first school, Mr. Paul's,

1836âSchool-life not favourable to his

characterâTo King's College School, 1837âThe

Cayley brothersâWhat Dante Rossetti learnedâHis

various Masters, including John Sell Cotman the painterâMr.

Caine's account of Rossetti's school-life discussedâParallel

with Edgar Poe's

school-lifeâSchool-fellowsâSchool-exercise on

China, and Christina Rossetti's verses thereon . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . 68

-

VIII.

HOME-LIFE DURING SCHOOLâSIR HUGH THE

HERON.

Polidori's country-house at Holmer Green, and his house in

Londonâ Accident with a chiselâBoyish

drawings from the IliadâDante Rossetti reads Byron, Dickens,

Brigand Tales, French novels, etc. âHe writes a prose tale,

Roderick and Rosalba

, and a ballad-poem,

Sir Hugh the Heron

, which is privately printed, also

William and Marie

â His note on

Hugh Heron

âBoyish drawingsâStudies German under Dr.

HeimannâIntimacy with the Heimann family . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

-

IX.

STUDY FOR THE PAINTING PROFESSIONâCARY'S AND

THE R.A.

Dante Rossetti leaves school, 1842, and goes to Cary's Drawing

AcademyâHis American friend, Thomas Doughty, and his family

âCharley Ware, and his portrait-groupâBailey's

Festus, and verses

The AtheistâStudies and habits at Cary'sâSonnets from

the Italian, and Bouts-rimés sonnetsâThe

Westminster Hall cartoon-competitionsâProceeds to the R.A.

antique school, 1846 âDisinclination to any obligatory study

or workâMillais, Holman Hunt, StephensâThe

Ghiberti GatesâHunt on Rossetti's appearance and

demeanourâA fellow-student's reminiscenceâ

Rossetti's immethodical habitsâTheatre-going . . . . . . . .

. . . . 88

-

X.

STUDENT-LIFEâSKETCHING, READING, AND

WRITING.

Rossetti's early sketches influenced by

GavarniâLithographed playing-cards, etc.âDesigns

to Christina Rossetti's

Verses, 1847âHis first uncompleted oil-picture,

Retro me Sathana

âReads Shelley, Charles Wells, Maturin, Thackeray, etc.,

and with great predilection BrowningâNo solid

readingâHis prose tale,

Sorrentino

, 1843âTranslations from the German,

The Nibelungenlied

,

Henry the Leper

, etc.âTranslations from the

Vita Nuova, and

Early Italian PoetsâTennyson's opinion of theseâThe printed

opinions of Swinburne and PlacciâWrites

The Blessed Damozel

, 1847âAdmiration of Edgar PoeâOther poems,

My Sister's Sleep

,

Ave

,

Dante at Verona

,

Jenny

, etc.âThe unpublished Ballad,

Jan van Hunks

, now begun, and finished on his deathbed â

Political burlesque poem,

unprintedâPurchase of the MS. book by

BlakeâRossetti's work, towards 1862, on Gilchrist's

Life of Blake

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .97

-

XI.

FRIENDS TOWARDS 1847.

Major Calder Campbell, Alexander Munro, William Bell

ScottâMeets Ebenezer JonesâRossetti's first letter

to Scott, 1847âObservations on his poemsâRossetti

sends

The Blessed Damozel

, and other

Songs of the Art Catholic

, to ScottâHis turn of mind in religious

mattersâScott's first visitâRossetti writes to

Browning about

Pauline, and knows him afterwards . . . . . . . . . . . 110

-

XII.

MADOX BROWN, HOLMAN HUNT, MILLAIS.

Letter to Madox Brown, 1848, asking to be allowed to study

painting under himâRossetti's relation to the course of study

at the R.A.â Details about Brown, and his first call on

RossettiâRossetti set to still-life painting,

etc.âHe calls on Hunt, and consults him as to further

painting-workâHis design of

Gretchen in the Church

â The Cyclographic SocietyâOpinions of

Millais and Hunt on the

Gretchen

âRossetti's indifference to perspective, in which

Stephens gives him some lessonsâForwards some poems to Leigh

Hunt, who (letter quoted) praises them, but dissuades him from trusting

to literature as a professionâ

Head of

Gaetano Polidori

, June 1848 âRossetti adopts

Holman Hunt's advice as to painting, and shares a studio with him in

Cleveland StreetâStephens's description of itâHunt

takes Rossetti round to Millais in Gower Street. 115

-

XIII.

THE PRÃRAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD.

Lasinio's engravings from the pictures in the Campo Santo of

Pisa lead on directly to the Præraphaelite movement,

1848âRemarks on Millais, Hunt, and Rossetti, in this

connexionâThe British school of painting in 1848, and the

term PræraphaeliteâThe three inventors of the

movement equally concerned in bringing it to bearâRossetti's

letter to Chesneau on this pointâTheir close attention to

detail subsidiary to other objects in the movementâ Madox

Brown's relation to the BrotherhoodâFour other members of

itâDetails as to Woolner, Collinson, Stephens, and

myselfâGreat intimacy among the P.R.B.'s.âHunt on

Rossetti's literary attainmentsâThe aims of the Brotherhood

discussedâ Not a religious movement, nor directly promoted by

Ruskinâ Rossetti, in later life, disliked the term

PræraphaeliteâDiary of the P.R.B. kept by me as

SecretaryâDefaced by Dante Rossetti

âDetails from this Diary as to

election of Deverell, etc.âThe P.R.B., as an organization,

dropped in January 1851âChristina's sonnet

The P.R.B.ââThe Queen of the

PræraphaelitesââRules adopted

1851âThe pictures of Millais, Hunt, and Rossetti, exhibited

in 1849âRossetti's

Girlhood of Mary Virgin

âThree sonnets of his bearing on the

movementâHis

portrait of Gabriele Rossetti, 1848 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

-

XIV.

FIRST EXHIBITED PICTURE, 1849.

Rossetti sends

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin

to the Free Exhibitionâ The works of the

Præraphaelites favourably received by critics and others in

1849, but very adversely afterwardsâThe

Athenæum

notice of Rossetti's first picture quotedâSale of the

picture, and its general successâTreatment in this book of

his pictures etc. in later years, and reference to another book,

Dante Gabriel Rossetti as Designer and

Writer

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

-

XV.

THE GERM.

Rossetti bent upon starting a magazine, July

1849âProposed titles and publisherâHe writes the

prose story

Hand and Soul

â Meeting at his studio, and choice of the title

The Germ

âContents of No. 1, and its saleâNos. 3 and 4

appear under the title

Art and Poetry

âNotices of the magazineâDebt upon its

issueâ Anecdotes relating to

Hand and Soul

âRossetti makes

an etching

(destroyed)

for this story, and begins another story

An Autopsychology

(or

St. Agnes of Intercession

)âHis various contributions to the

magazineâ Verses by John L. Tupper on its expiry . . 149

-

XVI.

PAINTINGS AND WRITINGS, 1849-53.

Trip with Holman Hunt to Paris and BelgiumâPaintings

and DesignsâRossetti's attainments in draughtsmanship,

etc.âDetails as to

Ecce Ancilla Domini

âPress-criticism of this picture, and other

Præraphaelite works of 1850âExtract from the

Athenæum

âThe Queen and Millais's

Carpenter's Shop

âDetails as to

Giotto painting Dante's Portrait

,

Head of Holman Hunt,

Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the

Pharisee

, and

Found

â

Discussion as to the statement that

Found

is an illustration of Bell Scott's poem

RosabellâRossetti's

sonnet to Woolner in AustraliaâCollinson's picture of

St. Elizabeth of Hungary â Sketching-club

proposed in 1854âPoems,

Dante at Verona

,

Burden of Nineveh

,

Sister Helen

, etc.âRossetti desultory in youth, and sometimes at

odds with his FatherâHe drops writing poetry,

1852âProject of his becoming a telegraphist on the

railwayâNotion of renting No. 16 Cheyne WalkâHis

studios in Newman Street and Red Lion SquareâBrown paints

Rossetti's head as ChaucerâRossetti settles in Chambers in

Chatham Place, 1852 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

-

XVII.

MISS SIDDAL.

Rossetti falls in love with Miss Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal,

1850â Walter H. Deverell first sees her as assistant in a

bonnet-shopâ Her appearanceâDeverell gets her to

sit for the head of Viola in

his picture

from

Twelfth NightâShe also sits to Hunt and MillaisâHer

familyâShe sits to Rossetti for

Rossovestita

, and a

subject from the

Vita Nuova, and many other paintingsâAn engagement between Miss

Siddal and Rossetti dating towards 1851âHer tone in

conversation, etc.âHer paintings and verses

âSwinburne's estimate of her quoted, also her poem

A Year and a DayâHer extreme ill-healthâShe is introduced to

the Howitt familyâRossetti as a loverâDeath of

Deverell, 1854 Â Â Â 171

-

XVIII.

JOHN RUSKIN.

Ruskin not connected with the Præraphaelite movement

when first startedâIn 1851 Patmore suggests to him to write

something on the subject, and he sends a letter to the

TimesâIn 1853 MacCracken calls his attention to Rossetti, and

Ruskin praises two of his water-coloursâRuskin calls on

Rossetti, April 1854âTheir intimacy begins, partly

interrupted by the death of Gabriele Rossetti, and the absence of Dante

Rossetti at Hastings, and of Ruskin abroadâAffectionate and

free-spoken relations between Ruskin and RossettiâMadox

Brown's dislike of Ruskin, who becomes the chief purchaser for a while

of Rossetti's worksâ Rossetti ceases to

exhibitâRuskin's opinion of Rossetti after his

deceaseâExtracts from Ruskin's letters, 1854-7âHis

high regard

Note: In section xx,

âMorteâ should read

âMortâ

for Miss SiddalâHe settles on her

£150 a year, taking her paintings in

proportionâCessation of this arrangement, 1857â

She goes abroad with Mrs. Kincaid, 1855, returning

1856âDecline of her healthâMy own acquaintance

with RuskinâRossetti admires him as a

lecturerâLetters from Rossetti to MacCracken, Extract . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178

-

XIX.

WORK IN 1854-5-6.

Water-colours from Dante, etc.â

Paolo and Francesca

,

Passover in Holy Family

,

Head of Browning

,

Dante's Dream

, Designs from Tennyson, etc.â

The Seed of David

, Triptych in Llandaff CathedralâGeneral characteristics

of Rossetti's style at this periodâ Troubles with the

Tennyson designs, and Tennyson's own views of themâSketches

of

Tennyson reading MaudâThe Seddons and the Triptychâ

The Blue Closet

, water-colour, and William Morrisâ

The Wedding of St. George

âJames Smetham, and his remarks hereon . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187

-

XX.

OXFORD MEN AND WORKâBURNE-JONES, MORRIS,

SWINBURNE

.

Friends of Rossetti between 1847 and

1855âBurne-Jones calls upon him, June 1856, and is advised by

Rossetti to adopt painting as a professionâAfterwards

Rossetti knows Morris and Swinburne âThe architect of the

Oxford Museum, Woodward, invites Rossetti in 1855 to undertake some

decorative work thereâHe does not do this, but in 1857 begins

painting in the Union Debating- Hall from the

Morte d' ArthurâMorris co-operatesâDetails as to the

Union-workâIn 1856 Rossetti

publishes

The Burden of Nineveh

and some other poems in the

Oxford and Cambridge Magazine

âRuskin on

The Burden of Nineveh

âOther painters in the Union HallâUltimate

spoiling of the workâSwinburne's introduction to

RossettiâRossetti and his friends see in Oxford Miss Burden,

who becomes Mrs. Morris, and from whom Rossetti paints many

headsâThe Præraphaelite Exhibition in Russell

Place, 1857âMiss Siddal's ill-health takes Rossetti to Bath,

etc. âProposal, not carried out, for a

âCollege,â in which he and other artists would

settleâMiss Siddal's dissentâHunt's statement as

to an âoffenceâ by Rossetti . . . .

. . 193

-

XXI.

WORK IN 1858-59.

Water-colour of

Mary in the House of John

, oil-picture

Bocca Baciata

, etc.âBell Scott's reference to the sitter for

Bocca Baciata

âMiss HerbertâPoems,

Love's Nocturn

, and

The Song of the Bower

â The Hogarth Club, 1858, and paintings there exhibited

. . 202

-

XXII.

MARRIAGE.

Reasons for postponing marriageâMr. Plint and other

purchasers of Rossetti's picturesâExtreme ill-health of Miss

Siddal at Hastings, April 1860âMarriage, 23

MayâWedding-trip to ParisâEnlargement of

Rossetti's view of pictorial artâHis designs in Paris,

How They Met Themselves

, etc.âHe returns with his wife to the Chambers,

afterwards enlarged, in Chatham Place . . . 204

-

XXIII.

MARRIED LIFE.

Bell Scott on Rossetti's unsuitableness for married

lifeâRemarks hereonâMrs. Rossetti intimate with

the Brown, Morris, and Burne-Jones familiesâRuskin on

drawings made by Rossetti from herâRossetti's intimacy with

Swinburneâalso with Meredith, Sandys, Gilchrist,

etc.âDeath of Gilchrist, 1861âMrs. Madox Brown's

offer to help during his illnessâMrs. Rossetti's infirm

health, and birth of a stillborn infantâDeath of Mrs. H. T.

Wells âRossetti speaks of â

getting awfully

fat and torpidâ . . . 208

-

XXIV.

WORK IN 1860-61â

THE EARLY

ITALIAN POETSâTHE

MORRIS FIRM.

Death of Plint, and embarrassment ensuing to Rossetti,

1860âThe Plint saleâWater-colours of

Lucrezia Borgia

and of Swinburne, design of

Cassandra

, oil-picture of

Fair Rosamund

, etc.âPreparations for publishing

The Early Italian Poets

âOpinions of Ruskin and PatmoreâPublished by

Smith and Elder, with some subsidizing from RuskinâFavourable

reception of the book, and result of its saleâProposed

etchings to it not producedâRossetti

shows some original poems to Ruskin, with a

view, unsuccessful, to publication in

The Cornhill MagazineâHe announces a volume,

Dante at Verona and other Poems

, not actually publishedâ Foundation in 1860 of the

firm, Morris, Marshall, Falkner, & Co. âSeven

members, including RossettiâDetails as to Webb, Marshall, and

FalknerâMoney ventured on the firmâGood-fellowship

of Rossetti and his partnersâMethods of business, more

especially of Morris as leading partner and managerâ

Warrington TaylorâRossetti's designs for stained glass, etc.

213

-

XXV.

DEATH OF MRS. DANTE ROSSETTI.

Her illness, phthisis and neuralgiaâThe last

painting for which she satâ10 February 1862, she dines at an

hotel with her husband and SwinburneâMy contemporary note as

to her death next morning from taking over-much laudanumâDr.

John Marshallâ Newspaper-paragraph, showing inquest, and

verdict of accidental deathâRossetti's sorrow and

agitationâRuskin calls, and exhibits a change in religious

opinionâThe funeralâRossetti consigns to the

coffin his book of MS. poemsâCaine's account of this incident

âRossetti's letter to Mrs. Gilchrist on his wife's death . .

. 220

-

XXVI.

SETTLING IN CHEYNE WALK.

Rossetti resolves to leave Chatham Place, and proposes to

combine with his family and Swinburne in getting a new

houseâHe fixes on No. 16 Cheyne WalkâRelinquishes

the proposal as to the familyâHis water-colour,

Girl at a Lattice

, and

crayon-head of his

Mother

âTakes chambers provisionally, 59 Lincoln's Inn

FieldsâNew arrangement for Cheyne Walk, Dante Rossetti as

tenant, with Swinburne, Meredith, and myself, as sub-tenantsâ

Condition of Cheyne Walk in 1862âCaine's account of the house

in 1880âFurther details as to the drawing-room

etc.âTaking possession of the house, October

1862âRossetti not constantly melancholy after his wife's

deathâMeredith and Swinburne as sub-tenants for the first two

or three yearsâMeredith's opinion of

RossettiâExtracts from letters from Ruskin and Burne-Jones,

1862âRossetti makes acquaintance with Whistler and

Legrosâ His art-assistant KnewstubâAdvance in

Rossetti's professional income . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . 227

-

XXVII.

WORK FROM 1862

TO 1868.

Oil-pictures,

Joan of Arc

,

Beata Beatrix

,

The Beloved

,

Lilith

,

Venus Verticordia

,

Sibylla Palmifera

,

Monna Vanna

,

Mrs. Morris

, etc. âWater-colours,

Paolo and Francesca

,

Return of Tibullus to Delia

,

Tristram and Yseult

, etc.âDesigns,

Michael Scott's Wooing

,

Aurea Catena

, etc.âDetails as to most of these works, also

Helen of Troy

,

Aurelia

,

The Boat of Love

,

The Blue Bower

,

Il Ramoscello

,

La Pia

,

Heart of the Night

,

Washing Hands

,

Socrates taught to Dance by Aspasia

,

Aspecta Medusa

âErroneous impression that Rossetti painted only from

Mrs. MorrisâOther sitters named, Christina Rossetti, Lizzie

Rossetti, Mrs. Hannay, Mrs. Beyer, Mrs. Hâ, Miss Wilding,

Miss Mackenzie, Keomi, Ellen Smith, Miss Graham, Mrs. Stillman, Mrs.

Sumner, etc.âRemarks on Mrs. Morris as his

typeâHis letter to the

Athenæum

as to his being a painter in oilsâShields on Rossetti's

use of compressed chalkâPurchasers of his works, Leathart,

Rae, Graham, Leyland, Valpy, Mitchell, Craven, Lord Mount-Temple,

Colonel Gillum, Trist, Gambart, Fairfax MurrayâInsufficiency

of Rossetti's studio, and its ultimate alterationâDunn

succeeds Knewstub as his art-assistantâLarge income made by

Rossetti in 1865 and other yearsâHis friendly relations with

purchasersâHis work 1862-3, in connexion with Gilchrist's

Life of Blake

. . . 238

-

XXVIII.

INCIDENTS, 1862

TO 1868.

Rossetti's animals at Cheyne WalkâHis notions about

ghostsâThe wombat, woodchuck, and zebuâAttempts to

communicate with his deceased wife by table-turningâThe

Burlington and other ClubsâThe

Bab BalladsâRossetti houses Sandys for a while, and George

ChapmanâOther friendsâCharles Augustus Howell, who

becomes Ruskin's secretaryâBell Scott and Woolnerâ

Intimacy with Ruskin comes to an endâExtracts from Ruskin's

letters in 1865âRossetti collects works of decorative art,

especially blue china and Japanese printsâBuys a picture by

Botticelli    251

-

XXIX.

BEGINNINGS OF ILL-HEALTHâPENKILL CASTLE.

Rossetti generally healthy in youthâ1866, a

complaint requiring surgical treatmentâ1867, insomnia, and

failure of eyesightâ

Doctors consultedâTrip to

Warwickshire in 1868, and stay at Penkill Castle, Ayrshire, with Miss

Boyd, Miss Losh, and Bell ScottâThe Leeds Exhibition of

ArtâLoan made by Miss Losh âReturn to Cheyne Walk,

and details as to eyesightâResumes art-work in December . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264

-

XXX.

PREPARATIONS FOR PUBLISHING POEMS.

Rossetti re-visits Penkill, 1869âUrged, in 1868, by

Scott to âlive for his poetryââSonnets

previously published in 1868, others in 1869âEstimate for

printingâPoems written at Penkill, 1869 âAlleged

impulse towards suicideâFancy about a

chaffinchââA curiously ferocious

lookââPoems printed, not for immediate

publicationâThe unburying of the MS. deposited in his wife's

coffinâArrangement with Ellis as

publisherâRossetti's combination of self-reliance and

self-mistrustâHe is anxious to secure a favourable critical

reception of the

Poems

at starting âExtracts on this point from my Diary and

from Scott's book âRossetti's habits as to

drinkingâDeath of Michael Halliday âAcquaintance

with Nettleship, Hake, and HuefferâHake's estimate of

Rossetti's character . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 270

-

XXXI.

ART-WORK FROM 1869

TO SUMMER 1872.

Oil-pictures of

Pandora

,

Mariana

,

Dante's Dream

,

Veronica Veronese

, etc.âWater-colour of

Michael Scott

âDesigns of

Penelope

, Dr. Hake, etc.âDetails as to some of these works,

especially

Dante's Dream

âW. A. Turner becomes a purchaser . . . 282

-

XXXII.

THE POEMS, 1870â

CHLORALâKELMSCOTT MANOR-HOUSE.

The

Poems forthcomingâSojourn at ScalandsâRossetti's

American friend Stillman, who recommends chloral as a

soporificâRossetti's excess in chloral-dosing, washed down by

whiskey, and the bad effects resultingâPublication of the

Poems

, April 1870âRapid saleâSwinburne's review,

extractsâOther reviews,

The Catholic World, etc.âLetters from acquaintancesâAdverse

criticism in

Blackwood's Magazine, coolly received by RossettiâRepublica-

tion of the Italian translations as

Dante and his Circle

, 1873âRossetti in 1871 at Kelmscott Manor-house, which

he shares with the Morris familyâPhilip Bourke Marston and

Edmund Gosse on RossettiâTurguenieffâPoems written

at Kelmscott . . . 285

-

XXXIII.

THE FLESHLY SCHOOL OF POETRY.

Robert Buchanan, as Thomas Maitland, publishes in the

Contemporary Review

an attack thus

entitled

on Rossetti's

Poems

, October 1871 âHis previous attack on Swinburne, 1866,

and my

Criticismâ Review of my edition of Shelley, 1870â

The Fleshly School enlarged and

re-issued as a pamphletâExtracts from

itâRossetti not much troubled by the

review-articleâA dinner at Bell Scott's âRossetti

replies, publishing, in the

Athenæum

,

The Stealthy School of Criticism

, and writing a pamphlet, which is withheldâ Aggravated

imputations in the pamphlet form of

The Fleshly SchoolâBuchanan's retractation, 1881-2,

extractsâSummary of the factsâQuilter's article

The Art of Rossetti, 1883, extract    293

-

XXXIV

HYPOCHONDRIA AND ILLNESS.

Dividing line in Rossetti's life, spring 1872âHe is

perturbed by

The Fleshly School of Poetry in its book-form, and has fancies of a conspiracy against

himâOther adverse critiquesâEvidences of mental

unsettlement on 2 JuneâBrowning regarded with suspicion

âRossetti not insane, but affected by hypochondria, resulting

largely from chloralâPhysical delusionsâMr.

Marshall and Dr. MaudsleyâExtract from the

Memoirs of Eighty Years, written by Dr. Hake, who takes Rossetti off to his house at

Roehampton âScott's remarksâAttempt at suicide by

laudanum on the night of 8 JuneâMistake as to serous

apoplexyâI fetch my Mother and Sister Maria, Christina being

illâBrown calls-in Marshall, who, along with Hake, saves

Rossetti's lifeâMental disturbance continues, and Rossetti

moves into Brown's house, followed by three houses in

PerthshireâHemiplegiaâRossetti's companions in

PerthshireâExtracts from Scott and HakeâResumption

of painting, and gradual recoveryâSurgical

treatmentâMoney-affairs âSale of the collection of

china, and removal of pictures to Scott's house . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 303

-

XXXV.

STAY AND WORK AT KELMSCOTT, 1872-4â

THEODORE

WATTS.

Rossetti, with George Hake, returns from Scotland, and

re-settles at Kelmscott Manor-houseâHis health and spirits at

first good, afterwards re-injured by chloralâPersonal

detailsâKnows Theodore Watts as a lawyer, and soon as an

intimate literary and personal friendâFixes upon Howell as

his professional agentâ Advantages accruing from this

connexionâJ. R. Parsons, Howell's partnerâRossetti

paints

Proserpine

, also

La Ghirlandata

,

The Bower Maiden

,

The Blessed Damozel

,

Dante's Dream

(smaller replica),

The Roman Widow

âRe-publishes

Dante and his Circle

âNonsense-versesâRecurrence of gloomy

fanciesâScott's cheque for £200âQuarrel

with anglersâRossetti leaves Kelmscott in July 1874, and

never returns thither . . . . . . . . . . . . 321

-

XXXVI.

LONDON AND ELSEWHERE, 1874-8.

Discussion of Bell Scott's statements about Rossetti's

seclusion, his desertion by old friends, George Hake, Browning, his new

friends, his want of candourâRossetti's condition of health

and mental toneâTheodore WattsâRossetti goes to

Aldwick Lodge, Bognor âLibel-case, Buchanan,

v. TaylorâGoes to BroadlandsâThe

Mount-Temples and Mrs.

SumnerââDeafeningâ of Rossetti's

studioâMesmerismâSurgical operation, as narrated

by Wattsâ Stay at Hunter's ForestallâDisappearance

of lettersâDetails as to chloralâBrown ceases to

see Rossetti for some monthsâ Renewal of lease in Cheyne

WalkâDeath of Oliver Brown, and Rossetti's impression as to

his posthumous writingsâDeath of Maria F. Rossetti . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 331

-

XXXVII.

INCIDENTS AND TRANSACTIONS, 1874-81â

HALL CAINE.

Dissolution of the Partnership, Morris, Marshall, Falkner,

& Co., 1874 âRossetti obtains possession of the

portrait of him painted by G. F. Watts, R.A.âHe drops his

connexion with Howell, 1876, and the reasons for

thisâDrawings falsely attributed to Rossetti

âFluctuations in his incomeâFunds for the families

of James Hannay and J. L. Tupper, and exertions to benefit James Smetham

âDeclines to exhibit in the Grosvenor Gallery,

1877âAn exception, for the benefit of an art-institution, to

his system of not

exhibitingâUnfounded report as

to a visit from the Princess LouiseâRossetti's correspondence

with Hall Caine begins, 1879 âExtract from Caine's

Recollections

as to his first visit to Rossetti, 1880âReference to

various details given by Caine as to Rossetti's opinions,

etc.âHis view debated as to Rossetti's natural irresolution

and melancholyâFriends who arranged to visit Rossetti from

day to dayâContinued activity in painting, along with poetry,

and the re-edition of Gilchrist's

Life of Blake . . . . 346

-

XXXVIII.

PAINTINGS AND POEMS, 1874-81.

Pictures of

The Blessed Damozel

,

Dante's Dream

(replica),

La Pia

,

La Bella Mano

,

Venus Astarte

,

The Sea-spell

,

Mnemosyne

,

Beata Beatrix

(finished by Madox Brown),

A Vision of Fiammetta

,

La Donna della Finestra

,

The Daydream

âDesigns of

The Sphinx

,

The Spirit of the Rainbow

,

Perlascura

,

Desdemona's Death-song

,

Sancta Lilias

,

The Sonnet

âWater-colour,

Bruna Brunelleschi

â Details as to

The Sea-spell

,

Vision of Fiammetta

,

Daydream

âScott's narrative as to

The Sphinx

âDetails as to

Desdemona's Death-song

and

Bruna Brunelleschi

â

Haydon's Etching of

Hamlet and Ophelia

âCaine's account as to how Rossetti resumed poetical

composition towards 1878â

Sonnet on CyprusâOther Sonnetsâ The historical ballads,

The White Ship

and

The King's Tragedy

â The

Beryl-songs in

Rose Mary

. . . . . . . . . . . 362

-

XXXIX.

DANTE'S DREAMâBALLADS AND SONNETS.

In July 1881 Hall Caine becomes an inmate of Rossetti's

houseâHis somewhat trying position thereâDunn

leaves the houseâ

Dante's Dream

returned to Rossetti, at his own wish, by Valpy, who is to receive

other works in exchangeâCaine suggests to the authorities of

the Walker Gallery, Liverpool, the purchase of this

pictureâAlderman Samuelson favours the

proposalâMr. R. and his proceedings in the same

matterâPurchase carried out for £1,650, September

1881âRecognition by Rossetti of the friendliness of Caine and

SamuelsonâTransactions with Valpy and GrahamâMarch

1881, Rossetti contemplates bringing out a new volume,

Ballads and Sonnets

, and re-issuing, in a modified form, the

Poems

of 1870âPublishing-arrangements, and rapid sale of

Ballads and Sonnets

in OctoberâProposed ballads on

Joan of Arc,

Abraham Lincoln, and

Alexander III. of

Scotland

âCritics favourable to the new

volumeâRossetti derives little pleasure from these successes

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 369

-

XL.

CUMBERLAND AND LONDONâFINAL ILLNESS.

Rossetti's state of health: blood-spitting, etc.âHe

goes with Caine to the Vale of St. John, Keswick, September

1881âReturns worse than he

wentââAbsolution for my sinsâ: Scott's

narrative, and observations on Rossetti's opinions upon

religionâPaintings:

Salutation of Beatrice

, duplicates of

Proserpine

and of

Joan of Arc

,

Donna della Finestra

âVisit from Dr. and Philip Marstonâ

Quasi-paralytic attack and discontinuance of chloralâAccount

by Caine, and extracts from my DiaryâScott and Morris on the

same subjectâThe Medical Resident Henry Maudsley, and the

Nurse Mrs. AbreyâRossetti, with Caine and Miss Caine, goes to

Birchington-on-SeaâScott's remarks on Rossetti's later

yearsâ Miss Caine's reminiscences . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . 375

-

XLI.

BIRCHINGTON-ON-SEA.

Birchington and Westcliff BungalowâRossetti's

condition thereâHe is joined by his Mother and

SisterâOther friendsâPaintings of

Proserpine

and of

Joan of Arc

, and sketches of his Father [

sketch 1] for VastoâBallad of

Jan van Hunks

, and

Sonnets on

The Sphinx

â Novel-readingâCorrespondence with Joseph

Knight and Ernest ChesneauâExtracts from Mrs. Rossetti's

Diary . . . . 390

-

XLII.

DEATH AND FUNERAL.

My visit to Birchington, 1 April 1882âExtracts from

my Diary, showing Dante's very grave condition of

healthâExtracts from Mrs. Rossetti's Diary, 4 to 9

AprilâRossetti's death, 9 AprilâMy memorandum of

itâHis willâArrival of Lucy Rossetti and Charlotte

PolidoriâThe funeral, further extracts from Mrs. Rossetti's

Diary, and letter from Judge LushingtonâThe tombstone,

stained-glass window, and monument in Cheyne Walk

395

-

XLIII.

PERSONAL DETAILSâEXTRACTS.

Rossetti's characterâCanon Dixon's

statementâRemarks by Knight, Patmore, and

WattsâHis appearanceâHis feeling as to the

beauties of NatureâHis views on

politicsâVarious remarks of his on fine art, literature, and

other matters, along with observations by Hunt, Caine, Sharp, Oliver

Brown, and myself . . 404

-

XLIV.

ROSSETTI AS PAINTER AND POETâEXTRACTS.

Decision not to offer my own criticism on this

matterâExtracts: upon Fine Art, Leighton, Royal Scottish

Academy, Hunt, Stephens, Quilter, Ruskin, Smetham, Shields, Hake, Rod,

Mourey, Sartorio âUpon Literature, Swinburne, Watts, Caine,

Forman, Knight, Hueffer, Sharp, Mrs. Wood, Patmore, Myers, William

Morris, Pater, Madame Darmesteter, Skelton, Sarrazin,

Gamberaleâ other Translators and Critics named . . . . . .

423

Â

- I.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1855. By Himself .

Frontispiece

- II.

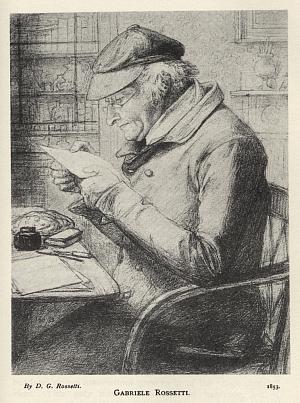

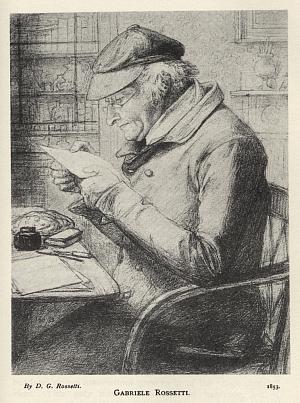

Gabriele Rossetti, 1853. By D. G. Rossetti .

To face p.

20

- III.

Gaetano Polidori, 1848. By D. G. Rossetti . ,, 123

- IV.

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal (Rossetti), 1854. By Herself . . . . . . . . . ,, 175

- V.

Christina G. Rossetti, 1848. By D. G. Rossetti ,, 342

Â

- Page xxi, line 12 from bottom,

for Morte read Mort

- ,, 14, line 11,

for dark-speaking

read

dark speaking

- ,, 54 ,, 8,

for Rufini

read Ruffini

- ,, 59 ,, 6,

for Fitz-Eustace

read De

Wilton

- ,, 119, lines 14, 15,

for I have not the least

recollection of what it was

read the

Study in

the manner of the Early Masters

- ,, 135, line 5,

for Fuhrich

read

Steinle

- ,, 166 ,, 11,

for never

read hardly

- ,, 199 ,, 17 etc.,

for I do not knowâ

etc. to end of paragraph, read These expressions occur in

a letter to Mr. Skelton

- ,, 235 ,, 19,

for the earlier days of 1864

read August 1863

- ,, 254 ,, 21,

for perhaps in 1863

read

in 1864

- ,, 274 ,, 17 etc.,

for I cannot sayâ

down to prominent among them

read Two of

these friends were Mr. Scott and Mr. Howell; perhaps also Mr. Henry Virtue

Tebbsâ

down to Doctors' Commons

- ,, 290 ,, 6 from bottom,

for forgot

read forget

- ,, 304 ,, 16,

for while

read wile

- ,, 336 ,, 22,

for public

read

published

- ,, 359 ,, 4 from bottom,

for latter

read former

- ,, 401 ,, 21,

for if not

read and

indeed

- ,, 409 ,, last,

for XXX

read IX

- ,, 418 ,, 17,

for lkely

read likely

- ,, 436 ,, 2,

for reputations

read

reputation,

- ,, ,, ,, 9,

for object

read

objects

MEMOIR

OF

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

BY

WILLIAM MICHAEL ROSSETTI.

- Be sure that Love ordained for souls more meek

- His roadside dells of rest.

Â

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti, commonly known as Dante

Gabriel Rossetti, was born on 12 May 1828, at No. 38 Charlotte Street,

Portland Place, London. This house is the last or most northerly

house, but one,

1 on the right-hand or eastern side of the street, as you turn into

it to the left, down Weymouth Street, out of Portland Place. Charlotte

Street, beyond No. 39, forms a

cul-de-sac. The infant was baptized at the neighbouring All Souls' Church,

Langham Place, as a member of the Church of England. From his father he

received the name Gabriel; from his godfather the name Charles; and from

poetical and literary associations the name Dante. His godfather was Mr.

Charles Lyell, of Kinnordy, Kirriemuir, Forfarshire; a keen votary of Dante

and Italian literature, a helpful friend to our father, and himself father

of the celebrated geologist, Sir Charles Lyell. Some living members of the

Lyell family continue to be well known to the present generation.

Transcribed Footnote (page 3):

1 No. 39 is now to the right hand of No. 38. It

appears to me that this was not the case when we lived in No. 38, but

that that was then the last house of all. The closed-up end of the

street has been wholly altered since my boyish days.

Â

Our parents were Gabriele Pasquale Giuseppe Rossetti

(always called Gabriele Rossetti), and Frances Mary Lavinia

Rossetti,

née Polidori; and, before proceeding further with my narrative, I

shall give some particulars about them, and about other members of the

family.

Gabriele Rossetti was born on 28 February 1783, in the city of Vasto,

named also (by a corruption from Longobard nomenclature) Vasto Ammone, in

the Province of Abruzzo Citeriore, on the Adriatic coast of the then Kingdom

of Naples. Vasto is a very ancient place, a municipal town of the Romans,

then designated Histonium. We are not boundâthough some

enthusiasts feel themselves permittedâ to believe that it was

founded by the Homeric hero Diomed: its patron saint is the Archangel

Michael. Gabriele was the youngest son of Nicola Rossetti, and his wife

Maria Francesca,

née Pietrocola. Nicola Rossetti was a Blacksmith,

of very moderate means;

1 a man of somewhat severe and irascible nature, whose death ensued

not long after the French-republican invasion of the Kingdom of Naples in

1799. The French put some affront upon himâI believe they gave

him a smart beating for failing or neglecting to furnish required

provisions; and, being unable to stomach this, or to resent it as he would

have liked, his health declined, and soon he was no more. His wife belonged

to a local family of fair credit: but, like other Italian women of that

period, she received no scholastic training; she could not write nor even

read. The name Rossetti might be translated into

âRuddykinsâ or âRedkinsâ as an

English

Transcribed Footnote (page 4):

1 A Vastese connexion of mine, Signor Giuseppe

Marchesani, favoured me, early in 1895, with a number of mortuary

and other inscriptions which he had composed to various members of

the family. I will give here the one relating to Nicola Rossetti,

who probably remains otherwise unrecorded, unless by some

âforlorn hic jacet.â Of course anything

written in a lapidary style reads less well in my English than in

Marchesani's Italian. âNicola Rossetti, Blacksmith

poor and honourable, lovingly sent in boyhood to their first

studies his sons, carefully nurtured in childhood. If Fortune

neglected him, provident Nature ultimately distinguished, in the

obscure Artizan, the well-graced Father, who, to the strokes of

his hammer on the battered anvil, sent forth the sonorous and

glorious echo, beyond remote Abruzzo, into Italy and other

lands.â

equivalent. My father used to say that the Rossetti

race was an offshoot of the Della Guardia family, well known and still

subsisting in Vasto; and that at some date or other certain children of the

Della Guardia stock were noted for florid complexion and reddish hair, and

thus got called âthe Rossetti,â in accordance with the

Italian hobby for nicknames, and that this name gradually stuck to them as a

patronymic.

Nicola and Maria Francesca Rossetti had a rather large family, four

sons and three daughters, and three of the sons earned distinction. There

was Domenico, who was versed (as a local historian records)

âin medical science, in civil and canonical law, and

in theology,â writing in Italian, Latin, French, and

to some extent Hebrew, and was âthe first among mortals

who daringly descended into the Grotto of Montecalvo near

Nice.â On this theme he wrote a poem in three cantos,

besides other poems (two volumes, printed in Parma) and prose: he was

besides an Improvisatore. Born in 1772, he

died comparatively young in 1816. There was also Andrea, the eldest brother,

who became a Canon of San Giuseppe in Vasto; and thirdly, Gabriele, whom I

may be excused for regarding as a more important writer than even the

polyglot Domenico. I might include, as showing that verse-writing ran in the

family, the fourth son, Antonio, who exercised the humble calling of a

wig-maker and barber: he likewise versified in an off-hand popular manner,

and was of some note to his fellow-townsmen.

Gabriele Rossetti came into the world well endowed for the arts. As it

turned out, he took to poetry and other forms of literature; but he might

equally have excelled in drawing or in vocal music. I have before me as I

write three MSS. containing specimens of his early skill as a draughtsman,

done when he was twenty years old or thereabouts. The drawings are

illustrations to poems (juvenile enough) of his own composition, and are

surprisingly precise and dainty in execution. One would have little

hesitation in calling them copper-engravings; but they are, in fact,

pen-designs done with sepia, which he himself extracted

from the cuttlefish or âcalamarello,â so dear to Neapolitan

gourmands. An ornamental headpiece, two decorative title- pages, and two

landscapes founded on traditions of Claude or Gaspar Poussin, are his own

inventions. One drawing is a group of two women after Mignard; and two or

three others may also be copies. From my earliest childhood I have looked

with astonishment on these performances as pieces of manipulation; and,

after a lifetime spent among artists, I hardly know what to put beside them

in their own limited line of attempt. Then, as to music, Gabriele had a

beautiful tenor-voice, sweet and sonorous in a high degree. It received no

regular cultivation, but was such that he was more than once urged to train

himself for the operatic stage âa mode of life, however, for

which he had no sort of inclination.

The local magnate was the Marchese del Vasto, of the great historic

house of D'Avalos, into which the famous Vittoria Colonna married. He was

feudal Lord of the Vastese, and they acknowledged themselves his

âvassals,â though this state of things, in the epoch

of a Robespierre and a Napoleon, was not destined to continue long. The

attention of the Marchese was soon called to the uncommon promise of his

growing-up vassal Gabriele Rossetti, and, after some well-conducted

schooling in Vasto, the youth was sent in 1804, under the patronage of this

nobleman, to study in the University of Naples. His education here was cut

short after a year and a month, and consequently had not a very wide range.

In middle life he read Latin with ease, and retained some remnant of

geometry and mathematics, but of Greek he had no knowledge. In French he was

well versed, speaking the language with great fluency and an amusing

assumption of the tone of a Frenchman. English he acquired by practice in

Malta and in this country, and could both read and talk it tolerably enough,

though he never did so when he had the option of Italian.

Rossetti was just twenty-three years of age when the Bourbon king,

Ferdinand I., was turned out of his continental

dominion, and had to retire into Sicily, and Joseph

Bonaparte reigned in his stead. With Ferdinand vanished the Marchese del

Vasto, who was his Court-Majordomo. Thus all the years of Rossetti's early

manhood were passed in association with a Napoleonic and not a Bourbon order

of ideas. As a sequel to his first volume of poems, published in 1807, he

obtained an appointment as librettist in the operatic theatre of San Carlo,

writing three or more opera-books, one of them named

Giulio Sabino. He was kept in hot water, however, by the exigencies of managers

and vocalists, and got transferred to the Curatorship of Ancient Marbles and

Bronzes in the Museum of Naples. He figured in the Academy of the Arcadi as

âFilidauro

Labidiense.â There used to be a catch,â

- âRossini,

Rossetti,

- Divini,

imperfettiâ;

but whether my father was ever linked with Rossini in any operatic

production I am unable to say. Rossetti was well received at the Court of

King Joachim (Murat), the successor of Joseph. I have heard him say that he

knew something of almost all the Bonapartes, except only the great Napoleon.

I possess a slight portrait of him done by the Princess Charlotte Bonaparte;

and another of the family, Lady Dudley Stuart, acted as godmother to his

daughter Christina. In my own time Prince Pierre Bonaparte (too notorious as

the homicide of Victor Noir) was frequently in our house; occasionally also

Prince Louis Napoleon, the unduly glorified and duly execrated Napoleon

III., of whom my father would emphatically declare that he could never trace

in him one grain (

neppure un' ombra) of Liberalism. King Joachim fell in 1815, and King Ferdinand was

restored to his capital city, Naples; a state of things not likely to be

much to the taste of Gabriele Rossettiâwho in 1813 had acted as

Secretary to that part of the provisional government, sent by Joachim to

Rome, which looked after public instruction and the fine arts. He did not,

however, under the

restored Bourbon, lose his post in the Museum. An

agitation ensued for a constitution similar to that which the Spaniards

established in 1819âthe secret society of the Carbonari, in which

Rossetti was a member of the General Assembly, being especially active in

this direction. In 1820 there was a military uprising, and Ferdinand had to

grant the constitution âprobably with a fixed intention of

revoking it at the first opportunity. Rossetti's ode to the Dawn of the

Constitution-day, âSei pur bella cogli astri sul

crineâ (âLovely art thou with stars in

hairâ), was in every Neapolitan mouth. In 1821 the king,

then sojourning in Austria, abolished the constitution, and suppressed it

with the aid of Austrian troops. Carbonarism was made a capital offence, and

the leading constitutionalists were denounced and proscribed, among them

Rossetti. He is said to have been viewed by the king with especial

abhorrence, partly because various writings, not really his, were attributed

to him, and partly because one of his lyrics contained the linesâ

- âI Sandi ed i

Luvelli

- Non son finiti

ancor,â

(Sands and Louvels are not yet extinct.) The reference, it will be

perceived, is to the political assassination of Kotzebue by Sand, and of the

Duc de Berri by Louvel, with a suggestion that a like fate might easily

befall King Ferdinand. Rossetti did not say that it

ought

to befall him; but the king was not inclined to take a good-natured view of

the matter, or to construe the phrase rather as a loyal warning than as an

incitement to a deed of blood. The peccant poet lay concealed in Naples for

three months, beginning in March 1821; finally the British admiral, Sir

Graham Moore, pressed by his generous wife who knew and liked Rossetti,

furnished him with a British uniform, got him off in a carriage to the

harbour, and shipped him to Malta. I have before me a printed proclamation

of King Ferdinandâ the original document, dated 28 September

1822âgranting an amnesty to persons concerned in the

revolutionary or

constitutional movement, with the exception of

thirteen men expressly named. My father is the thirteenth. In Malta he

remained about two years and a half, holding classes (as indeed he had

previously done in Naples) for instruction in the Latin and Italian

languages and literature, and most liberally befriended by the English poet

and diplomatist, John Hookham Frere, the translator of Aristophanes: their

amicable relations continued after distance had separated them. Deep indeed

were the affection and respect which Rossetti entertained for Frere. One of

my vivid reminiscences is of the day when the death of

Frere was announced to him,

1 in 1846. With tears in his half-sightless eyes and the passionate

fervour of a southern Italian, my father fell on his knees, and exclaimed,

âAnima bella, benedetta sii tu, dovunque

sei!â

2

Rossetti had long been a noted Improvisatore, as well as a poet in the accustomed way (he

continued to improvise to some extent for a while, even after coming to

London), and this, with his other gifts, made him popular in Maltese

society. After a while, however, he was harassed by the spies or other

emissaries of the Bourbon Government, which embittered his position so much

that he resolved to have done with Malta, and settle in England. Here he

arrived in January or February 1824, and fixed himself in London. He soon

made acquaintance with the Polidori family, and a mutual attachment united

him in marriage with the second daughter, Frances Mary Lavinia, in April

1826. He subsisted by teaching Italian, and held perhaps the foremost place

in that vocation. In 1831 he was appointed Professor of Italian in King's

College, London. This professorship was not a sinecure; but the students

were few, and became fewer from about 1840 onwards, when the German language

began decidedly to supersede the Italian in public favour. My

Transcribed Footnote (page 9):

1 The person who announced it was Mr. Edward

Graham, the associate of Shelley in early youth. He had taken to the

musical profession, and was a man of uncommonly handsome presence:

his bodily were superior to his mental endowments.

Transcribed Footnote (page 9):

2 âNoble soul, blessed be thou

wherever thou art.â

father made at the best a very moderate income;

yet this sufficed for all the requirements of himself, and his wife and four

children, and no man could be more heartily contented with what he

gotâmore strenuous and cheerful in working for it, or more

willing âto cut his coatâ (he never

turned it) âaccording to his cloth.â The

British religion of âkeeping up appearancesâ was

unknownâthank Heavenâin my paternal home; my father

disregarded it from temperament and foreign way of thinking and living, and

my mother contemned it with modest or noble superiority. The tolerably

thriving condition of our household declined with my father's decline in

health, which began towards 1842: interruption of professional work, waning

employment, inability to take up such employment as offered, necessarily

ensued. In 1843 (having hitherto had uncommonly keen eyesight) he suddenly

lost one eye through amaurosis, and the other eye was greatly weakened and

in constant peril, though he was never bereft of sight totally. A real

tussle for the means of subsistence now arose, but by one method or other

all was tided over. Our scale of living, if somewhat more threadbare and

dingy, did not materially dwindle from its unassuming yet comfortable

average; and no butcher nor baker nor candlestick-maker ever had a claim

upon us for a sixpence unpaid. In his closing years my father had more than

one stroke of paralysis. Some of these were of a formidable kind; yet he got

over them to a substantial extent, lived on in a suffering state of body,

and with mental faculties weakened, though not impaired in any definite and

absolute way, and continued diligent in reading and writing almost to the

last day of his life. His sufferings, often severe, were borne with patience

and courage (he had an ample stock of both qualities), though not with that

unemotional calm which would have been foreign to his Italian nature. For

nearly a year before his death he lived, with his wife and daughter

Christina, at Frome Selwood in Somerset; but finally he returned to London,

and died at No. 166 Albany Street, Regent's Park, on 26 April 1854,

firm-minded and placid, and glad to be

released, in the presence of all his family. His

young cousin, Teodorico Pietrocola-Rossetti, was also there. He lies buried

in Highgate Cemetery.

Gabriele Rossetti was man of energetic and lively temperament, of warm

affections, sensitive to slight or rebuff, and well capable of repelling it,

devoted to his family and home, full of good-nature and good-humour, a

fervent patriot, honourable and aboveboard in all his dealings, and as

pleasant and inspiriting company as one could wish to meet. Though sensitive

as above stated, he was not in the least quarrelsome, and never began a

conflict about either literary or personal matters: this disposition he

transmitted to his son Dante Gabriel. For some years after settling in

London he went a good deal into society, and was welcomed in several houses.

This had diminished at the date of my earliest reminiscences, and soon it

had wholly ceased. He could tell an amusing story most

capitallyâI have hardly known his equal at that âwith

good dramatic âtake-offâ; and, though his ordinary

speech was, to the best of my judgment, very pure Italian, he could readily

throw himself back, when he liked, into the Neapolitan dialect, or the

Abruzzese, which is not a little provincial.

1 He always spoke Italian in the family, never English; and his

children from the earliest years, as well as his wife, answered in Italian.

Apart from domestic simplicity or sportiveness, his conversation was always

high-minded, implying a solid standard of public and private virtue: nothing

about it mean or sly or worldly, or tampering with principle. There was

indeed a certain tinge of self-opinion or self-applause in his temperament;

he rather liked âto ride the high

horseâ (as I have heard my brother phrase

Transcribed Footnote (page 11):

1 I possess two good books showing the dialect

of Vasto, sent to me by the courtesy of their authors: the

Vocabolario dell' Uso

Abruzzese

, by Gennaro Finamore, and the

Fujj' Ammesche, by

Luigi Anelli. The latter volume is a series of sonnets, which appear

to me highly excellent of their popular kind. When I say that the

Vastese words âFujj'

Ammescheâ represent the Italian words

âFoglie

Miste,â my English reader will be able to judge

whether Vastese is a pure or impure form of Italian.

it); but this was quite free from envy or

disparagement of others, and did no one any harm. Of what one calls

âpersonal vanityâ he had a plentiful lack, and was

indeed very careless (like many other Italians) in all matters of the outer

man. As a father he was most kind, and would often allow his four children

to litter and rollick about the room while he plodded through some laborious

matter of literary composition. He always retained, however, a perceptible

tone of the

patria potestas. Rossetti was a

splendid declaimer or reciter, with perfect elocution. He put his heart into

whatsoever he did. His MSS. are models of fine and minute penmanship, and

show enormous pains in the way of revision and recasting.

He was an ardent lover of liberty, in thought and in the constitution

of society. In religion he was mainly a free-thinker, strongly anti-papal

and anti-sacerdotal, but not inclined, in a Protestant country, to abjure

the faith of his fathers. He never attended any place of worship. Spite of

his free-thinking, he had the deepest respect for the moral and spiritual

aspects of the Christian religion, and in his later years might almost be

termed an unsectarian and undogmatic Christian. As a freethinker, he was

naturally exempt from popular superstitionsâdid not believe in

ghosts, second sight, etc.; and the same statement holds good of our mother.

In this respect Dante Gabriel, as soon as his mind got a little formed,

differed from his parents; being quite willing to entertain, in any given

case, the question whether a ghost or demon had made his appearance or not,

and having indeed a decided bias towards suspecting that he had. One point,

however, of popular superstition, or I should rather say of superstitious

habit, my father had not discarded. A fancy existed in the Abruzzi (I dare

say it still exists) that, if one steps over a child seated or lying on the

ground, the child's growth would be arrested; and I have more than once seen

my father divert his path to avoid stepping over any one of us. In politics

he belonged more to the party of constitutional monarchy than to that of

republicanism, but welcomed

anything that told for freedom. He always

advocated the

unity of Italy, long before that aspiration

was considered a very practical one; indeed, I have seen him described, on

good authority, as the

first apostle of unity, but am not

clear that his is strictly accurate.

In estimating Rossetti's work as a national or patriotic poet, and his

general attitude of mind in matters of politics, or of government in State

and Church, we should remember the conditions (already referred to) under

which his life had been passed. He was born under the feudal and despotic

system of the Neapolitan Bourbons; his youth witnessed the more open-minded

but still despotic Napoleonic rule; the Bourbon restoration brought-on a

constitution sworn to by the sovereign, who soon after perjured himself in

suppressing it; lifelong exile ensured to Rossetti and other

constitutionalists. Then he lived through many abortive insurrections

against the temporal and ecclesiastical dominators of Italy; through the

brilliant promise and the retrogression of Pope Pius IX. (whom at first he

acclaimed with unmeasured fervour); through the high deeds, glorious

prospects, and dolorous collapse, of the revolutionary years 1848-49, and

through the fuliginous beginnings of the Neapolitan King Bomba; followed by

a genuinely liberal government in Piedmont under Victor Emmanuel and Cavour,

by the

coup d'état of Napoleon

III., and by general stagnancy of political thought and act throughout

Europe. He died five years before 1859, which produced the alliance between

France and Piedmont, the expulsion of the Austrians from Lombardy, and the

commencement of the unification of Italy. When he died in 1854 the outlook

seemed extremely dark; yet heart and hope did not abate in him. The latest

letter of his which I have seen published was written in September or

October 1853, and contains this passage, equally strong-spirited and propheticâ

âThe

Arpa Evangelica . . . ought to find free circulation through all Italy. I do not

say the like of three other unpublished volumes, which all seethe with

love of country and hatred for tyrants. These

Note: In the first paragraph, âdark-speakingâ should read

âdark speakingâ.

await a better timeâwhich will come, be very

sure of it. The present fatal period will pass, and serves to whet the

universal desire. . . . Let us look to the future. Our tribulations,

dear madam, will not finish very soon, but finish they will at last.

Reason has awakened in all Europe, although her enemies are strong. We

shall pass various years in this state of degradation; then we shall

rouse up. I assuredly shall not see it, for day by day, nay hour by

hour, I expect the much-longed-for death; but

you will

see it.â

In person Gabriele Rossetti was rather below the middle height, and

full in flesh till his health failed; with a fine brow, a marked prominent

nose and large nostrils, dark-speaking eyes, pleasant mouth, engaging smile,

and genuine laugh. He indulged in gesticulation, not to any great extent,

but of course more than an Englishman. His hands were rather

smallânot a little spoiled by a life-long habit of munching his

nails. As to other personal habits, I may mention free snuff-taking without

any smoking; and a hearty appetite while health lasted, with more of

vegetable diet than Englishmen use. In his later years teeth and palate had

failed, and all viands âtasted like hay.â Fermented

liquors he only touched seldom and sparingly. He had liked the English beer,

but had to leave it off altogether in 1836, to avoid recurrent attacks of

gout. In fact, he liked most things Englishâthe national and

individual liberty, the constitution, the people and their moral tone,

though the British leaven of social Toryism was far from being to his taste.

He certainly preferred the English nation, on the whole, to the French, and

had a kind of prepossession against Frenchwomen, which he pushed to a

humorous over-plus in speechâsaying for instance that, if a

Frenchwoman and himself were to be the sole tenants of an otherwise

uninhabited island, the human race on that island would decidedly not be

prolonged into a second generation. My father also took very kindly to the

English coal-fires, and was an adept in keeping them up; he would jocularly

speak of âbuying his climate at the

coal-merchant's.â In all my earlier years I used

frequently to see my father come home in the dusk rather fagged with his

round of teaching, and after dining he would lie

down flat on the hearthrug close by the fire, and fall asleep for an hour or

two, snoring vigorously. Beside him would stand up our old familiar tabby

cat, poised on her haunches, and holding on by the fore-claws inserted into

the fender-wires, warming her furry front. Her attitude (I have never seen

any feline imitation of it) was peculiar, somewhat in the shape of a capital

Yââthe cat making the Yâ

was my father's phrase for this performance. She was the mother of a

numerous progeny; one of her daughtersâalso long an inmate of our

houseâwas a black-and-white cat named Zoe by my elder sister

Maria, who had a fancy for anything Greekish; but Zoe never made a Y.

Rossetti had produced a tolerable amount of verse in Italy, also the

descriptive account (which passes under the name of Cavalier Finati) of the

Naples Museum; but all his more solid and voluminous writing was done after

he had settled in London. The principal works are as follows:

1826â

Dante, Commedia (the

Inferno alone was

published), with a Commentary aiming to show that the poem is chiefly

political and anti-papal in its inner meaning. A great deal of controversy

was excited at the time by this work, and by others which succeeded it.

1832â

Lo Spirito Antipapale che

produsse la Riforma

(

The Anti-Papal Spirit which produced the

Reformation

), following up and extending the same line of thought. An

English translation was also published. 1833â

Iddio e l'Uomo,

Salterio

(

God and Man, a Psaltery), poems. The two

last-named books have the honour of being in the Pontifical

Index Librorum

Prohibitorum

, edition 1838, and perhaps others are there now.

1840â

Il Mistero dell' Amor

Platonico del Medio Evo

(

The Mysterious Platonic Love of the Middle Ages),

five volumes; a book of daring and elaborately ingenious speculation,

enforcing the analogy of many illustrious writers, as forming a secret

society of anti-Catholic thought, with the doctrines of Gnosticism and

Freemasonry (Rossetti was himself a Freemason). This book was printed and

prepared for publication, but was withheld

Note: Type damage obscures page number.

(partly at the instance of Mr. Frere) as likely to be

accounted rash and subversive. 1842â

La Beatrice di Dante, contending that Dante's Beatrice was a symbolic personage, not a

real woman. 1846â

Il Veggente in

Solitudine

(

The Seer in Solitude), a poem of patriotic aim,

in a discursive and rhapsodical form, embodying a good deal of autobiography

and of earlier material. It circulated largely though clandestinely in

Italy, and a medal of Rossetti was struck there in commemoration.

1847â

Versi (miscellaneous poems). 1852â

L'Arpa Evangelica (

The Evangelic Harp), religious poems.

As regards my father's writings on Dante and other

authorsâthe outcome of an immense amount of miscellaneous, often

curious and abstruse, readingâI may be allowed to say that I

regard his views and arguments as cogent, without being convincing. They

affect one more in beginning one of his books than in ending it. He

certainly made some mistakes, and urged some details to a wiredrawn or

futile extreme, and in especial he was not sufficiently master of the happy

instinct when to leave off, so that his longest and most important book, the

Mistero dell' Amor

Platonico

, becomes cumbrous with subsidiary matter. In his poems also he was

over-fond of amplifying and loading, being too unwilling to leave a

composition as it stood; though he wrote with great mastery and ease, and a

brilliant command of metre, rhythm, and melody. Many snatches of his verse

are forcible and moving in a high degree, and rouse a contagious enthusiasm.

He has left in MS. a versified account of his life, written between 1846 and

1851. It is not long, nor yet very short, and is about the completest as

well as the most authentic account that exists of his career. I should like

to translate it some day, and publish it in England.

To give some idea of Rossetti's poetry, I cannot do better than

extract here one of the remarks upon it made by the pre-eminent Italian poet

of our own day, Giosuè Carducci, in a selection from Rossetti