Included Text

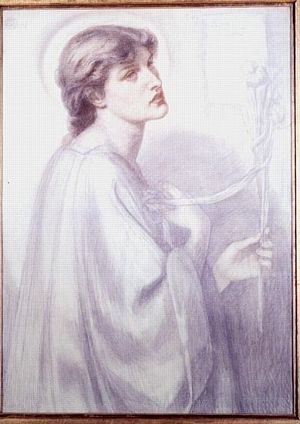

Aspice Lilias

Note: This is inscribed on a ribbon that extends from the lily, which it enwraps, to the lady's right hand, which rests near her

shoulder.

Sancta Lilias

Note: This is inscribed on a plaque at upper right.

Scholarly Commentary

Introduction

The picture is at least as important for its technical features as it is for its thematic relation to the central Rossettian subject of the emparadised or Beatricean woman.

DGR uses the picture to set in play a series of contradictions, as Surtees' general remark about the work suggests: “Head finished in red chalk, the rest of the figure sketched” (153). Is the work finished or isn't it? The head is carefully articulated and modelled whereas the hands are not only schematically drawn, their coloring is flat and marmoreal. And yet it is by no means clear that this differential signals an unfinished picture. On the contrary, the way the hands are drawn reflects the iris as well as the plaque that bears the faint but distinctive words “Sancta Lilias” and all possess, or are possessed by, the substance of the light with which they are structurally associated (see below).

Other related contradictions appear everywhere. In the Tate Gallery's Sancta Lilias , the iconic field supplies the woman's hair with some of its gold. Here the gold of the halo picks up some of the brown of the woman's hair, as if some part of her materiality had been absorbed into the transcendental order. One notes as well that the shadow cast by the figure echoes certain flesh tones from the neck and face. Furthermore, the structure of the picture's shadows is not logically arranged. A natural light source appears to have created the shadow that organizes itself on the right behind the woman, but the hands—in particular the left hand, which realistically ought to be in shadow— seem to emanate their own light, like the lady's face. The light in the upper part of the picture is clearly not generated by the “realistic” light source outside and in front of the picture, but is rather a function of the emblematic forms that define the deepest plane, the halo and the plaque (or is it some kind of window?). Thus the woman's physical person is drawn into a relation with halo and plaque as a light source that can oppose the fall of the natural light in which she stands.

The space of the picture is similarly arranged. The woman stands about forty degrees to the picture plane, while the plaque at the rear plane, inscribed with words, declares that its plane and the picture plane are parallel. When DGR then forces the illusion that the circle of the halo and the rectangle of the plaque stand on the same plane, the implicit narrative of the portrait gets distorted, like the space of the picture in general. For the halo appears to possess an independent spatial existence, as if the lady's head had been arbitrarily placed in it (rather than as if her face and head emanated an aureole). The flatness of the halo is all the more striking because of the angle of the lady's head, which turns across the angle of her body.

The picture is at once finished and unfinished, natural and non-natural. As such, its formal characteristics articulate its central thematic concerns.

Production History

The date on the picture does not explain the circumstances that led DGR to do it in 1879. Returning at such a late date to the subject he had handled so elaborately in The Blessed Damozel and its many associated works seems odd unless he had a commission to do so. But no record of such a commission is recorded. In his Tabular List of DGR's pictures, WMR simply lists this work, which carries no further commentary.

Reception

According to Marillier, this was “a very popular” work. His remark is odd because the picture has no exhibition history at all, nor do we know very much about its contemporary production circumstances.

Iconograpic

As in so many of DGR's pictures of ideal women, the figure here wears the “loose-fitting dress based upon fourteenth-century design” (Shefer 10) that he had made a special feature of his work from The Girlhood of Mary Virgin . Shefer points out that “this dress symbolized bohemianism and a free style of living” (Shefer 11).

Pictorial

The picture is closely related to The Blessed Damozel —indeed, it is a variant of the damozel, as the Tate Gallery's oil painting titled Sancta Lilias shows: the latter is a cut-down state of a version of The Blessed Damozel . Marillier says the 1879 picture “may have been intended for an Annunciation picture”.

Literary

The picture is closely related to The Blessed Damozel by virtue of its pictorial connection to the painting The Blessed Damozel .

Bibliography