Rossetti Archive Textual Transcription

The full Rossetti Archive record for this transcribed document is available.

OF

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

OF

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

EDITED

WITH PREFACE AND NOTES

BY

WILLIAM M ROSSETTI

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOLUME I

POEMS

PROSEâTALES AND LITERARY PAPERS

ELLIS AND SCRUTTON

LONDON

1886

All rights reserved

Printed by Hazell, Watson, & Viney, Ld., London and Aylesbury.

DIED 9 APRIL 1882 AGED 53

FRANCES MARY LAVINIA ROSSETTI

DIED 8 APRIL 1886 AGED 85

TO

THE MOTHER'S SACRED MEMORY

THIS FIRST COLLECTED EDITION OF

THE SON'S WORKS

IS DEDICATED BY

THE SURVIVING SON AND BROTHER

W M R

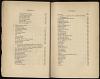

- Preface by William M. Rossetti . . . . . xv

-

-

POEMS.

-

-

I.â

Principal Poems:â

- Dante at Verona . . . . . . . . 1

- A Last Confession . . . . . . . . 18

- The Bride's Prelude . . . . . . . 35

- Sister Helen . . . . . . . . . 66

- The Staff and Scrip . . . . . . . . 75

- Jenny . . . . . . . . . . 83

- The Stream's Secret . . . . . . . 95

- Rose Mary . . . . . . . . . 103

- The White Ship . . . . . . . . 137

- The King's Tragedy . . . . . . . 148

-

-

The House of Life, A

Sonnet-Sequenceâ

-

- Introductory Sonnet . . . . . . . 176

-

-

Part

I.âYouth and

Change:â

- 1. Love Enthroned . . . . . . 177

- 2. Bridal Birth . . . . . . . 177

- 3. Love's Testament . . . . . . 178

- 4. Lovesight . . . . . . . 178

- 5. Heart's Hope . . . . . . 179

- 6. The Kiss . . . . . . . 179

- 7. Supreme Surrender . . . . . 180

- 8. Love's Lovers . . . . . . 180

- 9. Passion and Worship . . . . . 181

- 10. The Portrait . . . . . . . 181

- 11. The Love-letter . . . . . . 182

- 12. The Lover's Walk . . . . . 182

- 13. Youth's Antiphony . . . . . 183

- 14. Youth's Spring-tribute . . . . . 183

- 15. The Birth-bond . . . . . . 184

- 16. A Day of Love . . . . . . 184

- 17. Beauty's Pageant . . . . . . 185

- 18. Genius in Beauty . . . . . . 185

- 19. Silent Noon . . . . . . . 186

- 20. Gracious Moonlight . . . . . 186

- 21. Love-sweetness . . . . . . 187

- 22. Heart's Haven . . . . . . 187

- 23. Love's Baubles . . . . . . 188

- 24. Pride of Youth . . . . . . 188

- 25. Winged Hours . . . . . . 189

- 26. Mid-rapture . . . . . . . 189

- 27. Heart's Compass . . . . . . 190

- 28. Soul-light . . . . . . . 190

- 29. The Moonstar . . . . . . 191

- 30. Last Fire . . . . . . . 191

- 31. Her Gifts . . . . . . . 192

- 32. Equal Troth . . . . . . . 192

- 33. Venus Victrix . . . . . . 193

- 34. The Dark Glass . . . . . . 193

- 35. The Lamp's Shrine . . . . . 194

- 36. Life-in-love . . . . . . . 194

- 37. The Love-moon . . . . . . 195

- 38. The Morrow's Message . . . . . 195

- 39. Sleepless Dreams . . . . . . 196

- 40. Severed Selves . . . . . . 196

- 41. Through Death to Love . . . . 197

- 42. Hope Overtaken . . . . . . 197

- 43. Love and Hope . . . . . . 198

- 44. Cloud and Wind . . . . . . 198

- 45. Secret Parting . . . . . . 199

- 46. Parted Love . . . . . . . 199

- 47. Broken Music . . . . . . 200

- 48. Death-in-love . . . . . . 200

- 49, 50, 51, 52. Willow-wood . . . . 201

- 53. Without Her . . . . . . 203

- 54. Love's Fatality . . . . . . 203

- 55. Stillborn Love . . . . . . 204

- 56, 57, 58.

True Woman

(HerselfâHer

Loveâ

Her Heaven) . . . . . 204 - 59. Love's Last Gift . . . . . . 206

-

-

Part

II.âChange and

Fate:â

- 60. Transfigured Life . . . . . 207

- 61. The Song-Throe . . . . . . 207

- 62. The Soul's Sphere . . . . . 208

- 63. Inclusiveness . . . . . . 208

- 64. Ardour and Memory . . . . . 209

- 65. Known in Vain . . . . . . 209

- 66. The Heart of the Night . . . . 210

- 67. The Landmark . . . . . . 210

- 68. A Dark Day . . . . . . . 211

- 69. Autumn Idleness . . . . . . 211

- 70. The Hill Summit . . . . . . 212

- 71, 72, 73. The Choice . . . . . 212

- 74, 75, 76.

Old and New

Art (St. Luke the Painter

âNot as TheseâThe Husbandmen) 214 - 77. Soul's Beauty . . . . . . 215

- 78. Body's Beauty . . . . . . 216

- 79. The Monochord . . . . . . 216

- 80. From Dawn to Noon . . . . . 217

- 81. Memorial Thresholds . . . . . 217

- 82. Hoarded Joy . . . . . . . 218

- 83. Barren Spring . . . . . . 218

- 84. Farewell to the Glen . . . . . 219

- 85. Vain Virtues . . . . . . . 219

- 86. Lost Days . . . . . . . 220

- 87. Death's Songsters . . . . . . 220

- 88. Hero's Lamp . . . . . . . 221

- 89. The Trees of the Garden . . . . 221

- 90. Retro me, Sathana . . . . . 222

- 91. Lost on Both Sides . . . . . 222

- 92, 93. The Sun's Shame . . . . . 223

- 94. Michelangelo's Kiss . . . . . 224

- 95. The Vase of Life . . . . . . 224

- 96. Life the Beloved . . . . . . 225

- 97. A Superscription . . . . . . 225

- 98. He and I . . . . . . . 226

- 99, 100. Newborn Death . . . . . 226

- 101. The One Hope . . . . . . 227

-

-

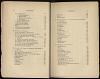

II.âMiscellaneous Poems:â

- My Sister's Sleep . . . . . . . . 229

- The Blessed Damozel . . . . . . . 232

- At the Sunrise in 1848 . . . . . . . 237

- Autumn Song . . . . . . . . . 237

- The Lady's Lament . . . . . . . . 238

- The Portrait . . . . . . . . . 240

- Ave . . . . . . . . . . . 244

- The Card-Dealer . . . . . . . . 248

- World's Worth . . . . . . . . 250

- On Refusal of Aid between Nations . . . . 252

- On the Vita Nuova of Dante . . . . . . 252

- Song and Music . . . . . . . . 253

- The Sea-Limits . . . . . . . . 254

-

A Trip to Paris and Belgium

(London to Folkestoneâ

Boulogne to Amiens and ParisâThe Paris Railway-

stationâReaching BrusselsâAntwerp to Ghent) . 255 - The Staircase of Notre Dame, Paris . . . . 261

- Place de la Bastille, Paris . . . . . . 261

- Near BrusselsâA Halfway Pause . . . . . 262

- Antwerp and Bruges . . . . . . . 263

- On Leaving Bruges . . . . . . . 264

- Vox Ecclesiæ Vox Christi . . . . . . 265

- The Burden of Nineveh . . . . . . . 266

- The Church Porch . . . . . . . . 272

- The Mirror . . . . . . . . . 272

- A Young Fir-Wood . . . . . . . 273

- During Music . . . . . . . . . 273

- Stratton Water . . . . . . . . 274

- Wellington's Funeral . . . . . . . 280

- Penumbra . . . . . . . . . 283

-

On the Site of a Mulberry-Tree,

planted by William

Shakespeare, etc. . . . . . . . 285 - On certain Elizabethan Revivals . . . . . 285

- English May . . . . . . . . . 286

- Beauty and the Bird . . . . . . . 286

- A Match with the Moon . . . . . . . 287

- Love's Nocturn . . . . . . . . 288

- First Love Remembered . . . . . . . . . 293

- Plighted Promise . . . . . . . . 294

- Sudden Light . . . . . . . . . 295

- A New Year's Burden . . . . . . . 296

- Even So . . . . . . . . . . 297

- The Woodspurge . . . . . . . . 298

- The Honeysuckle . . . . . . . . 298

- Dantis Tenebræ . . . . . . . . 299

- Words on the Window-pane . . . . . . 299

- An Old Song Ended . . . . . . . 300

- The Song of the Bower . . . . . . . 301

- Dawn on the Night Journey . . . . . . 303

- A Little While . . . . . . . . 304

- Troy Town . . . . . . . . . 305

- Eden Bower . . . . . . . . . 308

- Love-lily . . . . . . . . . . 315

- Sunset Wings . . . . . . . . . 316

- The Cloud Confines . . . . . . . . 317

- Down-Stream . . . . . . . . . 319

- Three Shadows . . . . . . . . 321

- A Death-parting . . . . . . . . 322

- Spring . . . . . . . . . . 323

- Untimely LostâOliver Madox Brown . . . . 323

- Parted Presence . . . . . . . . 324

- Spheral Change . . . . . . . . 326

- Alas, So Long! . . . . . . . . 327

- Insomnia . . . . . . . . . . 328

- Possession . . . . . . . . . 329

- Chimes . . . . . . . . . . 330

- Adieu . . . . . . . . . . 333

- Soothsay . . . . . . . . . . 334

-

Five English

Poets:â

- 1. Thomas Chatterton . . . . . . 337

- 2. William Blake . . . . . . . 338

- 3. Samuel Taylor Coleridge . . . . . 338

- 4. John Keats . . . . . . . . 339

- 5. Percy Bysshe Shelley . . . . . . 339

- To Philip Bourke Marston . . . . . . 340

- Tiber, Nile, and Trafalgar . . . . . . 340

- Raleigh's Cell in the Tower . . . . . . 341

- Winter . . . . . . . . . . 341

- The Last Three from Trafalgar . . . . . 342

- Czar Alexander the Second . . . . . . 342

-

III.âSonnets on

Pictures:â

- For an Annunciation. Early German . . . . 343

- For our Lady of the Rocks, by Leonardo da Vinci . . 344

- For a Venetian Pastoral, by Giorgione . . . . 345

-

For an Allegorical Dance of Women,

by Andrea

Mantegna . . . . . . . . . 346 - For Ruggiero and Angelica, by Ingres . . . . 347

- For a Virgin and Child, by Hans Memmelinck . . 348

- For a Marriage of St. Catherine, by the same . . . 349

- For the Wine of Circe, by Edward Burne Jones . . 350

- For the Holy Family, by Michelangelo . . . . 351

- For Spring, by Sandro Botticelli . . . . . 352

-

IV.âSonnets and Verses for Rossetti's own

Works of

- Mary's Girlhood . . . . . . . . 353

- The Passover in the Holy Family . . . . . 355

- Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the Pharisee . 356

- Michael Scott's Wooing . . . . . . . 357

- Aspecta Medusa . . . . . . . . 357

- Cassandra . . . . . . . . . 358

- Venus Vesticordia . . . . . . . . 360

- Pandora . . . . . . . . . . 360

- A Sea-spell . . . . . . . . . 361

- Astarte Syriaca . . . . . . . . 361

- Mnemosyne . . . . . . . . . 362

- Fiametta . . . . . . . . . 362

- Found . . . . . . . . . . 363

- The Day-dream . . . . . . . . 364

Art:â-

V.âPoems in Italian (or Italian and English),

French,

- Gioventù e Signoria . . . . . . . . 366

- Youth and Lordship . . . . . . . 367

- Proserpina . . . . . . . . . 370

- La Ricordanza . . . . . . . . . 370

- Proserpina . . . . . . . . . 371

- Memory . . . . . . . . . . 371

- La Bella Mano . . . . . . . . 372

- Con Manto d'Oro, etc. . . . . . . . 372

- Robe d'Or, etc. . . . . . . . . 372

- La Bella Mano . . . . . . . . 373

- With Golden Mantle, etc. . . . . . . 373

- A Golden Robe, etc. . . . . . . . 373

- Barcarola . . . . . . . . . 374

- Barcarola . . . . . . . . . 375

- Bambino Fasciato . . . . . . . . 375

- Thomæ Fides . . . . . . . . . 376

and Latin:â-

VI.âVersicles and Fragments:â

- The Orchard-pit . . . . . . . . 377

- To Art . . . . . . . . . . 378

- On Burns . . . . . . . . . 378

- Fin di Maggio . . . . . . . . . 378

- I saw the Sibyl at Cumæ . . . . . . 378

- As balmy as the breath, etc. . . . . . . 378

- Was it a friend, etc. . . . . . . . 379

- At her step, etc. . . . . . . . . 379

- Would God I knew, etc. . . . . . . 379

- I shut myself in with my soul . . . . . . 379

- If I could die, etc. . . . . . . . . 379

- She bound her green sleeve, etc. . . . . . 379

- Where is the man, etc. . . . . . . . 380

- As much as in a hundred years she's dead . . . 380

- Who shall say, etc. . . . . . . 380

-

-

-

PROSE.

-

-

I.âStories and Schemes of

Poems:â

- Hand and Soul . . . . . . . . 383

- Saint Agnes of Intercession . . . . . . 399

- The Orchard-pit . . . . . . . . 427

- The Doom of the Sirens . . . . . . . 431

- The Cup of Water . . . . . . . . 437

- Michael Scott's Wooing . . . . . . . 439

- The Palimpsest . . . . . . . . 441

- The Philtre . . . . . . . . . 442

-

-

II.âLiterary Papers:â

- William Blake . . . . . . . . . 443

- Ebenezer Jones . . . . . . . . 478

- The Stealthy School of Criticism . . . . . 480

- Hake's Madeline, and other Poems . . . . . 489

- Hake's Parables and Tales . . . . . . 500

- III.âSentences and Notes. . . . . . 510

-

- Notes by William M. Rossetti . . . . . 513

Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as of most

authors, would probably be to offer a broad general

view of his writings, and to analyse with some critical

precision his relation to other writers, contemporary or

otherwise, and the merits and defects of his performances.

In this case, as in how few others, one would also have

to consider in what degree his mind worked con-

sentaneously or diversely in two several artsâthe art of

poetry and the art of painting. But the hand of a

brother is not the fittest to undertake any work of this

scope. My preface will not therefore deal with themes

such as these, but will be confined to minor matters,

which may nevertheless be relevant also within their

limits. And first may come a very brief outline of the

few events of an outwardly uneventful life.

of his professional career, modified his name into Dante

Gabriel Rossetti, was born on 12th May 1828, at No.

38 Charlotte Street, Portland Place, London. In blood

he was three-fourths Italian, and only one-fourth Eng-

lish; being on the father's side wholly Italian (Abruzzese),

and on the mother's side half Italian (Tuscan) and half

English. His father was Gabriele Rossetti, born in

1783 at Vasto, in the Abruzzi, Adriatic coast, in the then

kingdom of Naples. Gabriele Rossetti (died 1854) was

Museo Borbonico of Naples, and a poet; he distinguished

himself by patriotic lays which fostered the popular

movement resulting in the grant of a constitution by

Ferdinand I. of Naples in 1820. The King, after the

fashion of Bourbons and tyrants, revoked the constitution

in 1821, and persecuted the abettors of it, and Rossetti

had to escape for his freedom, or perhaps even for his

life. He settled in London towards 1824, married, and

became Professor of Italian in King's College, London,

publishing also various works of bold speculation in the

way of Dantesque commentary and exposition. His

wife was Frances Mary Lavinia Polidori (died 1886),

daughter of Gaetano Polidori (died 1853), a teacher of

Italian and literary man who had in early youth been

secretary to the poet Alfieri, and who published various

books, including a complete translation of Milton's

poems. Frances Polidori was English on the side of

her mother, whose maiden name was Pierce. The

family of Rossetti and his wife consisted of four

children, born in four successive yearsâMaria Fran-

cesca (died 1876), Dante Gabriel, William Michael, and

Christina Georgina, the two last-named being now the only

survivors. Few more affectionate husbands and fathers

have lived, and no better wife and mother, than Gabriele

and Frances Rossetti. The means of the family were

always strictly moderate, and became scanty towards

1843, when the father's health began to fail. In or about

that year Dante Gabriel left King's College School, where

he had learned Latin, French, and a beginning of Greek;

and he entered upon the study of the art of painting, to

which he had from earliest childhood exhibited a very

marked bent. After a while he was admitted to the

yond its antique section. In 1848 Rossetti co-operated

with two of his fellow-students in painting, John Everett

Millais and William Holman Hunt, and with the sculptor

Thomas Woolner, in forming the so-called Præraphaelite

Brotherhood. There were three other members of the

BrotherhoodâJames Collinson (succeeded after two or

three years by Walter Howell Deverell), Frederic

George Stephens, and the present writer. Ford Madox

Brown, the historical painter, was known to Rossetti

much about the same time when the Præraphaelite

scheme was started, and bore an important part both in

directing his studies and in upholding the movement,

but he did not think fit to join the Brotherhood in any

direct or complete sense. Through Deverell, Rossetti

came to know Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, daughter of a

Sheffield cutler, herself a milliner's assistant, gifted with

some artistic and some poetic faculty; in the Spring of

1860, after a long engagement, they married. Their

wedded life was of short duration, as she died in

February 1862, having meanwhile given birth to a still-

born child. For several years up to this date Rossetti,

designing and painting many works, in oil-colour or as

yet more frequently in water-colour, had resided at

No. 14 Chatham Place, Blackfriars Bridge, a line of

street now demolished. In the autumn of 1862 he re-

moved to No. 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. At first

certain apartments in the house were occupied by Mr.

George Meredith the novelist, Mr. Swinburne the poet,

and myself. This arrangement did not last long,

although I myself remained a partial inmate of the house

up to 1873. My brother continued domiciled in Cheyne

Walk until his death; but from about 1869 he was

frequently away at Kelmscot manorhouse, in Oxford-

shire, not far from Lechlade, occupied jointly by himself,

and by the poet Mr. William Morris with his family.

From the autumn of 1872 till the summer of 1874 he

was wholly settled at Kelmscot, scarcely visiting London

at all. He then returned to London, and Kelmscot

passed out of his ken.

Præraphaelite Brotherhood, with the co-operation of

some friends, brought out a short-lived magazine named

The Germ (afterwards Art and Poetry); here appeared

the first verses and the first prose published by Rossetti,

including The Blessed Damozel and Hand and Soul .

In 1856 he contributed a little to The Oxford and

Cambridge Magazine , printing there The Burden of

Nineveh . In 1861, during his married life, he published

his volume of translations The Early Italian Poets , now

entitled Dante and his Circle . By the time therefore of

the death of his wife he had a certain restricted yet far

from inconsiderable reputation as a poet, along with his

recognized position as a painterâa non-exhibiting painter,

it may here be observed, for, after the first two

or three years of his professional course, he ad-

hered with practical uniformity to the plan of abstaining

from exhibition altogether. He had contemplated bring-

ing out in or about 1862 a volume of original poems;

but, in the grief and dismay which overwhelmed

him in losing his wife, he determined to sacri-

fice to her memory this long-cherished project, and he

buried in her coffin the manuscripts which would have

furnished forth the volume. With the lapse of years he

came to see that, as a final settlement of the matter,

this was neither obligatory nor desirable; so in 1869 the

manuscripts were disinterred, and in 1870 his volume

named Poems was issued. For some considerable

while it was hailed with general and lofty praise,

chequered by only moderate stricture or demur; but

late in 1871 Mr. Robert Buchanan published under a

pseudonym, in the Contemporary Review , a very hostile

article named The Fleshly School of Poetry , attacking

the poems on literary and more especially on moral

grounds. The article, in an enlarged form, was after-

wards reissued as a pamphlet. The assault produced

on Rossetti an effect altogether disproportionate to its

intrinsic importance; indeed, it developed in his cha-

racter an excess of sensitiveness and of distempered

brooding which his nearest relatives and friends had

never before surmised,âfor hitherto he had on the whole

had an ample sufficiency of high spirits, combined with

a certain underlying gloominess or abrupt moodiness of

nature and outlook. Unfortunately there was in him

already only too much of morbid material on which this

venom of detraction was to work. For some years the

state of his eyesight had given very grave cause for appre-

hension, he himself fancying from time to time that the

evil might end in absolute blindness, a fate with which

our father had been formidably threatened in his closing

years. From this or other causes insomnia had ensued,

coped with by far too free a use of chloral, which may

have begun towards the end of 1869. In the summer of

1872 he had a dangerous crisis of illness; and from that

time forward, but more especially from the middle of

1874, he became secluded in his habits of life, and often

depressed, fanciful, and gloomy. Not indeed that there

were no intervals of serenity, even of brightness; for in

fact he was often genial and pleasant, and a most agreeable

companion, with as much bonhomie as acuteness for wiling

an evening away. He continued also to prosecute his

pictorial work with ardour and diligence, and at times he

added to his product as a poet. The second of his original

volumes, Ballads and Sonnets , was published in the

autumn of 1881. About the same time he sought change

of air and scene in the Vale of St. John, near Keswick,

Cumberland; but he returned to town more shattered in

health and in mental tone than he had ever been before.

In December a shock of a quasi-paralytic character struck

him down. He rallied sufficiently to remove to Birching-

ton-on-Sea, near Margate. The hand of death was then

upon him, and was to be relaxed no more. The last

stage of his maladies was uræmia. Tended by his

mother and his sister Christina, with the constant com-

panionship at Birchington of Mr. Hall Caine, and in the

presence likewise of Mr. Theodore Watts, Mr. Frederick

Shields, and myself, he died on Easter Sunday, April 9th

1882. His sister-in-law, the daughter of Madox Brown,

arrived immediately after his latest breath had been

drawn. He lies buried in the churchyard of Birchington.

one another's feelings and thoughts more intimately, in

childhood, boyhood, and well on into mature manhood,

than Dante Gabriel and myself. I have no idea of

limning his character here at any length, but will de-

fine a few of its leading traits. He was always and

essentially of a dominant turn, in intellect and in

temperament a leader. He was impetuous and vehe-

ment, and necessarily therefore impatient; easily

angered, easily appeased, although the embittered

feelings of his later years obscured this amiable quality

to some extent; constant and helpful as a friend where

he perceived constancy to be reciprocated; free-handed

and heedless of expenditure, whether for himself or for

others; in family affection warm and equable, and (except

in relation to our mother, for whom he had a fondling

love) not demonstrative. Never on stilts in matters of

the intellect or of aspiration, but steeped in the sense

of beauty, and loving, if not always practising, the good;

keenly alive also (though many people seem to discredit

this now) to the laughable as well as the grave or solemn

side of things; superstitious in grain, and anti-scientific

to the marrow. Throughout his youth and early man-

hood I considered him to be markedly free from vanity,

though certainly well equipped in pride; the distinction

between these two tendencies was less definite in his

closing years. Extremely natural and therefore totally

unaffected in tone and manner, with the naturalism

characteristic of Italian blood; good-natured and hearty,

without being complaisant or accommodating; reserved

at times, yet not haughty; desultory enough in youth,

diligent and persistent in maturity; self-centred always,

and brushing aside whatever traversed his purpose or

his bent. He was very generally and very greatly liked

by persons of extremely diverse character; indeed, I

think it can be no exaggeration to say that no one ever

disliked him. Of course I do not here confound the

question of liking a man's personality with that of

approving his conduct out-and-out.

impression. I have said that it was natural; it was

likewise eminently easy, and even of the free-and-easy

kind. There was a certain British bluffness, streaking

the finely poised Italian suppleness and facility. As he

was thoroughly unconventional, caring not at all to

fall in with the humours or prepossessions of any

particular class of society, or to conciliate or approxi-

mate the socially distinguished, there was little in him

of any veneer or varnish of elegance; none the less he

was courteous and well-bred, meeting all sorts of persons

upon equal termsâ i.e., upon his own terms; and I am

satisfied that those who are most exacting in such

matters found in Rossetti nothing to derogate from the

standard of their requirements. In habit of body he was

indolent and lounging, disinclined to any prescribed

or trying exertion of any sort, and very difficult to stir

out of his ordinary groove, yet not wanting in active

promptitude whenever it suited his liking. He often

seemed totally unoccupied, especially of an evening;

no doubt the brain was busy enough.

Italian than English, though I have more than once

heard it said that there was nothing observable to

bespeak foreign blood. He was of rather low middle

stature, say five feet seven and a half, like our father;

and, as the years advanced, he resembled our father

not a little in a characteristic way, yet with highly

obvious divergences. Meagre in youth, he was at

times decidedly fat in mature age. The complexion,

clear and warm, was also dark, but not dusky or sombre.

The hair was dark and somewhat silky; the brow grandly

spacious and solid; the full-sized eyes blueish-grey;

the nose shapely, decided, and rather projecting, with an

aquiline tendency and large nostrils, and perhaps no

detail in the face was more noticeable at a first glance

than the very strong indentation at the spring of the

nose below the forehead; the mouth moderately well-

shaped, but with a rather thick and unmoulded under-

lip; the chin unremarkable; the line of the jaw, after

youth was passed, full, rounded, and sweeping; the ears

well-formed and rather small than large. His hips were

wide, his hands and feet small; the hands very much

those of the artist or author type, white, delicate,

plump, and soft as a woman's. His gait was resolute

and rapid, his general aspect compact and deter-

mined, the prevailing expression of the face that

of a fiery and dictatorial mind concentrated into re-

pose. Some people regarded Rossetti as eminently

handsome; few, I think, would have refused him the

epithet of well-looking. It rather surprises me to

find from Mr. Caine's book of Recollections that that

gentleman, when he first saw Rossetti in 1880, con-

sidered him to look full ten years older than he really

was,ânamely, to look as if sixty-two years old. To my

own eye nothing of the sort was apparent. He wore

moustaches from early youth, shaving his cheeks; from

1870 or thereabouts he grew whiskers and beard, mode-

rately full and auburn-tinted, as well as moustaches. His

voice was deep and harmonious; in the reading of poetry,

remarkably rich, with rolling swell and musical cadence.

the interruption of his ordinary habits of life, and the

flurry or discomfort, involved in locomotion. In boy-

hood he knew Boulogne: he was in Paris three or four

times, and twice visited some principal cities of Belgium.

This was the whole extent of his foreign travelling.

He crossed the Scottish border more than once, and

knew various parts of England pretty wellâHastings,

Bath, Oxford, Matlock, Stratford-on-Avon, Newcastle-

on-Tyne, Bognor, Herne Bay; Kelmscot, Keswick, and

Birchington-on-Sea, have been already mentioned. From

1878 or thereabouts he became, until he went to the

neighbourhood of Keswick, an absolute home-keeping

recluse, never even straying outside the large garden of

his own house, except to visit from time to time our

mother in the central part of London.

friends, and could always have commanded any amount

of intercourse with any number of ardent or kindly

well-wishers, had he but felt elasticity and cheerfulness

of mind enough for the purpose. I should do injustice

to my own feelings if I were not to mention here some

of his leading friends. First and foremost I name Mr.

Madox Brown, his chief intimate throughout life, on

the unexhausted resources of whose affection and con-

verse he drew incessantly for long years; they were at

last separated by the removal of Mr. Brown to Man-

chester, for the purpose of painting the Town Hall

frescoes. The PræraphaelitesâMillais, Hunt, Woolner,

Stephens, Collinson, Deverellâwere on terms of un-

bounded familiarity with him in youth; owing to death

or other causes, he lost sight eventually of all of them

except Mr. Stephens. Mr. William Bell Scott was, like

Mr. Brown, a close friend from a very early period until

the last; Scott being both poet and painter, there was

a strict bond of affinity between him and Rossetti.

Mr. Ruskin was extremely intimate with my brother

from 1854 till about 1865, and was of material help to

his professional career. As he rose towards celebrity,

Rossetti knew Burne Jones, and through him Morris

and Swinburne, all staunch and fervently sympathetic

friends. Mr. Shields was a rather later acquaintance,

who soon became an intimate, equally respected and

cherished. Then Mr. Hueffer the musical critic (now

a close family connection, editor of the Tauchnitz edition

of Rossetti's works), and Dr. Hake the poet. Through

the latter my brother came to know Mr. Theodore

Watts, whose intellectual companionship and incessant

assiduity of friendship did more than anything else

towards assuaging the discomforts and depression of his

closing years. In the latest period the most intimate

among new acquaintances were Mr. William Sharp and

Mr. Hall Caine, both of them known to Rossettian readers

as his biographers. Nor should I omit to speak of the

extremely friendly relation in which my brother stood to

some of the principal purchasers of his picturesâMr.

Leathart, Mr. Rae, Mr. Leyland, Mr. Graham, Mr. Valpy,

Mr. Turner, and his early associate Mr. Boyce. Other

names crowd upon meâJames Hannay, John Tupper,

Patmore, Thomas and John Seddon, Mrs. Bodichon,

Browning, John Marshall, Tebbs, Mrs. Gilchrist, Miss

Boyd, Sandys, Whistler, Joseph Knight, Fairfax Murray,

Mr. and Mrs. Stillman, Treffry Dunn, Lord and Lady

Mount-Temple, Oliver Madox Brown, the Marstons,

father and sonâbut I forbear.

sequence, etc., of my brother's writings, it may be worth

while to speak of the poets who were particularly

influential in nurturing his mind and educing its own

poetic endowment. The first poet with whom he

became partially familiar was Shakespeare. Then fol-

lowed the usual boyish fancies for Walter Scott and

Byron. The Bible was deeply impressive to him,

perhaps above all Job, Ecclesiastes, and the Apocalypse.

Byron gave place to Shelley when my brother was about

sixteen years of age; and Mrs. Browning and the old

English or Scottish ballads rapidly ensued. It may have

been towards this date, say 1845, that he first seriously

applied himself to Dante, and drank deep of that in-

exhaustible well-head of poesy and thought; for the

Florentine, though familiar to him as a name, and in

some sense as a pervading penetrative influence, from

earliest childhood, was not really assimilated until boy-

hood was practically past. Bailey's Festus was enor-

mously relished about the same timeâread again and

yet again; also Faust, Victor Hugo, De Musset (and

along with them a swarm of French novelists), and

Keats, whom my brother for the most part, though not

without some compunctious visitings now and then,

truly preferred to Shelley. The only classical poet

whom he took to in any degree worth speaking of was

Homer, the Odyssey considerably more than the Iliad.

Tennyson reigned along with Keats, and Edgar Poe and

Coleridge along with Tennyson. In the long run he

perhaps enjoyed and revered Coleridge beyond any other

modern poet whatsoever; but Coleridge was not so

distinctly or separately in the ascendant, at any par-

ticular period of youth, as several of the others. Blake

likewise had his peculiar meed of homage, and Charles

Wells, the influence of whose prose style, in the Stories

after Nature , I trace to some extent in Rossetti's Hand

and Soul . Lastly came Browning, and for a time, like

the serpent-rod of Moses, swallowed up all the rest.

This was still at an early stage of life; for I think the

year 1847 cannot certainly have been passed before my

brother was deep in Browning. The readings or frag-

mentary recitations of Bells and Pomegranates, Para-

celsus , and above all Sordello, are something to remember

from a now distant past. My brother lighted upon

Pauline (published anonymously) in the British Museum,

copied it out, recognized that it must be Browning's, and

wrote to the great poet at a venture to say so, receiving

a cordial response, followed by a genial and friendly inter-

course for several years. One prose-work of great

influence upon my brother's mind, and upon his product

as a painter, must not be left unspecifiedâMalory's

Mort d'Arthur, which engrossed him towards 1856.

The only poet whom I feel it needful to add to the

above is Chatterton. In the last two or three years of

his life my brother entertained an abnormalâI think

an exaggeratedâadmiration of Chatterton. It appears

to me that (to use a very hackneyed phrase) he âevolved

this from his inner consciousnessâ at that late period;

certainly in youth and early manhood he had no such

feeling. He then read the poems of Chatterton with

cursory glance and unexcited spirit, recognizing them

as very singular performances for their date in English

literature, and for the author's boyish years, but beyond

that laying no marked stress upon them.

names unmentioned in this list: I have stated the facts

as I remember and know them. Chaucer, Spenser,

the Elizabethan dramatists (other than Shakespeare),

Milton, Dryden, Pope, Wordsworth, are unnamed. It

should not be supposed that he read them not at all, or

cared not for any of them; but, if we except Chaucer in

a rather loose way and (at a late period of life) Marlowe

in some of his non-dramatic poems, they were compara-

tively neglected. Thomas Hood he valued highly; also

very highly Burns in mature years, but he was not

a constant reader of the Scottish lyrist. Of Italian poets

he earnestly loved none save Dante: Cavalcanti in his

degree, and also Poliziano and Michelangelo â not

Petrarca, Boccaccio, Ariosto, Tasso, or Leopardi, though

in boyhood he delighted well enough in Ariosto. Of

French poets, none beyond Hugo and De Musset;

except Villon, and partially Dumas, whose novels ranked

among his favourite reading. In German poetry he

read nothing currently in the original, although (as our

pages bear witness) he had in earliest youth so far

mastered the language as to make some translations.

Calderon, in Fitzgerald's version, he admired deeply;

but this was only at a late date. He had no liking for

the specialities of Scandinavian, nor indeed of Teutonic,

thought and work, and little or no curiosity about

Orientalâsuch as Indian, Persian, or Arabicâpoetry.

Any writing about devils, spectres, or the supernatural

generally, whether in poetry or in prose, had always

a fascination for him; at one time, say 1844, his supreme

delight was the blood-curdling romance of Maturin,

Melmoth the Wanderer.

writings. Of his merely childish or boyish performances

I need have said nothing, were it not that they have

been mentioned in other books regarding Rossetti. First

then there was The Slave , a âdramaâ which he

composed and wrote out in or about the sixth year of his

age. It is of course simple nonsense. âSlaveâ and

âtraitorâ were two words which he found passim in

Shakespeare; so he gave to his principal or only

characters the names of Slave and Traitor. If what

they do is meaningless, what they say (when they deviate

from prose) is probably unmetrical; but it is so long

since I read The Slave that I speak about this with

uncertainty. Towards his thirteenth year he began

a romantic prose-tale named Roderick and Rosalba . I

hardly think that he composed anything else prior to

the ballad narrative Sir Hugh the Heron , founded on

a tale by Allan Cunningham. Our grandfather printed it

in 1843, which is probably the year of its composition.

It is correctly enough versified, but has no merit, and

little that could even be called promise. Soon afterwards a

prose-tale named Sorrentino , in which the devil played

a conspicuous part, was begun, and carried to some

length; it was of course boyish, but it must, I think, have

shown some considerable degree of cleverness. In 1844

or 1845 there was a translation of Bürger's Lenore ,

spirited and I suppose fairly efficient; and in November

1845 was begun a translation of the Nibelungenlied ,

almost deserving (if my memory serves me) to be con-

sidered good. Several hundred lines of it must certainly

have been written. My brother was by this time a

practised and competent versifier, at any rate, and his

mere prentice-work may count as finished.

succeeded, along with the version of Der Arme Heinrich ,

and the beginning of his translations from the early

Italians. These must, I think, have been in full career

in the first half of 1847, if not in 1846. They show

a keen sensitiveness to whatsoever is poetic in the

originals, and a sinuous strength and ease in providing

English equivalents, with the command of a rich and

romantic vocabulary. In his nineteenth year, or before

12th May 1847, he wrote The Blessed Damozel .* As

that is universally recognized as one of his typical

* My brother said so, in a letter published by Mr. Caine. He

must

presumably have been correct; otherwise I should have

thought

that his twentieth year, or even his twenty-first, would

be

nearer the mark.

his faculty whether inventive or executive, I may here

close this record of preliminaries; the poems, with such

slight elucidations as my notes supply, being left to

speak for themselves. I will only add that for some

while, more especially in the later part of 1848 and in

1849, my brother practised his pen to no small extent in

writing sonnets to bouts-rimés. He and I would sit

together in our bare little room at the top of No. 50

Charlotte Street, I giving him the rhymes for a sonnet,

and he me the rhymes for another; and we would write

off our emulous exercises with considerable speed, he

constantly the more rapid of the two. From five to eight

minutes may have been the average time for one of his

sonnets; not unfrequently more, and sometimes hardly

so much. In fact, the pen scribbled away at its fastest.

Many of his bouts-rimés sonnets still exist in my posses-

sion, a little touched up after the first draft. Two or

three seemed to me nearly good enough to appear in the

present collection, but on the whole I decided against

them all. Some have a faux air of intensity of meaning,

as well as of expression; but their real core of signifi-

cance is necessarily small, the only wonder being how

he could spin so deftly with so weak a thread. I may

be allowed to mention that most of my own sonnets (and

not sonnets alone) published in The Germ were bouts-

rimes experiments such as above described. In poetic

tone they are of course inferior to my brother's work of

like fashioning; in point of sequence or self-congruity of

meaning, the comparison might be less to my disadvantage.

three volumes, chiefly of poetry. I shall transcribe the

title-pages verbatim.

Dante Alighieri (1100â1200â1300) in the Original

Metres. Together with Dante's Vita Nuova. Translated

by D. G. Rossetti. Part I. Poets chiefly before Dante.

Part II. Dante and his Circle. London: Smith, Elder

and Co., 65, Cornhill. 1861. The rights of translation

and reproduction, as regards all editorial parts of this

work, are reserved.

ceding him (1100â1200â1300). A Collection of Lyrics,

edited, and translated in the original metres, by Dante

Gabriel Rossetti. Revised and rearranged edition.

Part I. Dante's Vita Nuova, &c. Poets of Dante's

Circle. Part II. Poets chiefly before Dante. London:

Ellis and White, 29 New Bond Street. 1874.

London: Ellis and White, 29 New Bond Street. 1881.

London: Ellis and White, 29, New Bond Street, W. 1881.

same book as 1 a, but altered in arrangement, chiefly

by inverting the order in which the poems of Dante

and of the Dantesque epoch, and those of an earlier

period, are printed. In the present collection, I reprint

1 b, taking no further count of 1 a. The volume 2 b is to

a great extent the same as 2 a, yet by no means identical

with it. 2 a contained a section named Sonnets and

Songs, towards a work to be called âThe House of Life.â

In 1881, when 2 b and 3 were published simultaneously,

The House of Life was completed, was made to consist

solely of sonnets, and was transferred to 3; while the

gap thus left in 2 b was filled up by other poems. With

this essential modification of The House of Life it was

clearly my duty not to interfere.

but the question had to be considered whether I should

reprint 2 b and 3 exactly as they stood in 1881, adding

after them a section of poems not hitherto printed in

any one of my brother's volumes; or whether I should

recast, in point of arrangement, the entire contents of

2 b and 3, inserting here and there, in their most appro-

priate sequence, the poems hitherto unprinted. I have

chosen the latter alternative, as being in my own opinion

the only arrangement which is thoroughly befitting for

an edition of Collected Works. I am aware that some

readers would have preferred to see the old orderâ i.e.,

the order of 1881âretained, so that the two volumes of

that year could be perused as they then stood. Indeed,

one of my brother's friends, most worthy, whether as

friend or as critic, to be consulted on such a subject,

decidedly advocated that plan. On the other hand, I

found my own view confirmed by my sister Christina,

who, both as a member of the family and as a poetess,

deserved an attentive hearing. The reader who inspects

my table of contents will be readily able to follow the

method of arrangement which is here adopted. I have

divided the materials into Principal Poems, Miscellaneous

Poems, Translations, and some minor headings; and

have in each section arranged the poemsâand the

same has been done with the prose-writingsâin some

approximate order of date. This order of date is cer-

tainly not very far from correct; but I could not make it

absolute, having frequently no distinct information to go

by. The few translations which were printed in 2 b (as

shall give in a tabular form some particulars which will

enable the reader to follow out for himself, if he takes

an interest in such minutiæ, the original arrangement of

2 a, 2 b, and 3.

yet, which I am unable to include among his Collected

Works. One of these is a grotesque ballad about a

Dutchman, begun at a very early date, and finished in

his last illness. The other is a brace of sonnets, in-

teresting in subject, and as being the very last thing

that he wrote. These works were presented as a gift

of love and gratitude to a friend, with whom it remains

to publish them at his own discretion. I have also

advisedly omitted three poems; two of them sonnets,

the third a ballad of no great length. One of the

sonnets is that entitled Nuptial Sleep . It appeared in

the volume of Poems 1870 (2 a), but was objected

to by Mr. Buchanan, and I suppose by some other

censors, as being indelicate; and my brother excluded

it from The House of Life in his third volume. I con-

sider that there is nothing in the sonnet which need

imperatively banish it from his Collected Works; but

his own decision commands mine, and besides it could

not now be reintroduced into The House of Life ,

which he moulded into a complete whole without it,

and would be misplaced if isolated by itselfâa point

as to which his opinion is very plainly set forth in

his prose-paper The Stealthy School of Criticism . The

second sonnet, named On the French Liberation of Italy,

was put into print by my brother while he was pre-

paring his volume of 1870, but he resolved to leave

it unpublished. Its title shows plainly enough that it

part; but the subject is treated under the form of a

vigorous and perhaps repulsive metaphor, and here

again I follow his own lead. The ballad above referred

to, Dennis Shand , is a skilful and really very harmless

production; it was printed but not published, like the

sonnet last-mentioned, and no writer other than one

who took a grave view of questions of moral propriety

would have preferred to suppress it. My brother's

opinion is worded thus in a letter to Mr. Caine, which

that gentleman has published: âThe ballad . . . deals

trivially with a base amour (it was written very early),

and is therefore really reprehensible to some extent.â

I will not be less jealously scrupulous for him than he

was for himself.

might add, a very fastidious painter. He did not indeed

âcudgel his brainsâ for the idea of a poem or the

structure or diction of a stanza. He wrote out of a

large fund or reserve of thought and consideration,

which would culminate in a clear impulse or (as we

say) an inspiration. In the execution he was always

heedful and reflective from the first, and he spared no

after-pains in clarifying and perfecting. He abhorred

anything straggling, slipshod, profuse, or uncondensed.

He often recurred to his old poems, and was reluctant to

leave them merely as they were. A natural concomitant

of this state of mind was a great repugnance to the

notion of publishing, or of having published after his

death, whatever he regarded as juvenile, petty, or

inadequate. As editor of his Collected Works, I have

had to regulate myself by these feelings of his, whether

my own entirely correspond with them or not. The

was by no means large; out of the moderate bulk I

have been careful to select only such examples as I

suppose that he would himself have approved for the

purpose, or would, at any rate, not gravely have objected

to. A list of the new items is given at page xli, and a

few details regarding them will be found among my

notes. Some projects or arguments of poems which he

never executed are also printed among his prose-writings.

These particular projects had, I think, been practically

abandoned by him in all the later years of his life; but

there was one subject which he had seriously at heart,

and for which he had collected some materials, and he

would perhaps have put it into shape had he lived a

year or two longerâa ballad on the subject of Joan Darc,

to match The White Ship and The King's Tragedy .

he considered himself more essentially a poet than a

painter. To vary the form of expression, he thought that

he had mastered the means of embodying poetical concep-

tions in the verbal and rhythmical vehicle more thoroughly

than in form and design, perhaps more thoroughly than

in colour.

to publish at an early date a substantial selection from

the family-letters written by my brother, to be pre-

ceded by a Memoir drawn up by Mr. Theodore Watts,

who will be able to express more freely and more im-

partially than myself some of the things most apposite

to be said about Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

London, June 1886.

-

LIST OF THE POEMS PUBLISHED BY DANTE

-

- 2a.âContents of

Poems, 1870.

-

-

Poems:

- The Blessed Damozel . . . . . . i. . 232

- Love's Nocturn . . . . . . . i. . 288

- Troy Town . . . . . . . . i. . 305

- The Burden of Nineveh . . . . . i. . 266

- Eden Bower . . . . . . . . i. . 308

- Ave . . . . . . . . . i. . 244

- The Staff and Scrip . . . . . . i. . 75

- A Last Confession . . . . . . i. . 18

- Dante at Verona . . . . . . . i. . 1

- Jenny . . . . . . . . i. . 83

- The Portrait . . . . . . . . i. . 240

- Sister Helen . . . . . . . . i. . 66

- Stratton Water . . . . . . . i. . 274

- The Stream's Secret . . . . . . i. . 95

- The Card-dealer . . . . . . . i. . 248

- My Sister's Sleep . . . . . . . i. . 229

- A New Year's Burden . . . . . . i. . 296

- Even So . . . . . . . . i. . 297

- An Old Song Ended . . . . . . i. . 300

- Aspecta Medusa . . . . . . . i. . 357

- Three Translations from Villon . . . . ii.461,etc.

- John of Tours . . . . . . . ii. . 465

- My Father's Close . . . . . . ii. . 467

- One Girl ( now named Beauty) . . . . ii. . 469

-

Sonnets and Songs towards a Work to be entitled

âThe

House of Life.â - Fifty Sonnets . . . . . . i. 177, etc.

- [For the titles of them see vol. i., p. 517.]

-

-

Songs:

- Love-lily . . . . . . . . i. . 315

- First Love Remembered . . . . . i. . 293

- Plighted Promise . . . . . . . i. . 294

- Sudden Light . . . . . . . i. . 295

- A Little While . . . . . . . i. . 304

- The Song of the Bower . . . . . . i. . 301

- Penumbra . . . . . . . . i. . 283

- The Woodspurge . . . . . . . i. . 298

- The Honeysuckle . . . . . . . i. . 298

- A Young Fir-wood . . . . . . i. . 273

- The Sea Limits . . . . . . . i. . 254

- [Here ended the âHouse of Lifeâ Series.]

-

-

Sonnets for Pictures, and other

Sonnets:

- For Our Lady of the Rocks, by Leonardo da

- Vinci . . . . . . . . i. . 344

- For a Venetian Pastoral, by Giorgione . . . i. . 345

- For an Allegorical Dance of Women, by Man-

- tegna . . . . . . . . i. . 346

- For Ruggiero and Angelica, by Ingres . . . i. . 347

- For the Wine of Circe, by Burne Jones . . i. . 350

- Mary's Girlhood . . . . . . . i. . 353

- The Passover in the Holy Family . . . . i. . 355

- Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the

- Pharisee . . . . . . . . i. . 356

- St. Luke the Painter . . . . . . i. . 214

- Lilith . . . . . . . . . i. . 216

- Sibylla Palmifera . . . . . . . i. . 215

- Venus . . . . . . . . . i. . 360

- Cassandra . . . . . . . . i. . 358

- Pandora . . . . . . . . . i. . 360

- On Refusal of Aid between Nations . . . i. . 252

- On the Vita Nuova of Dante . . . . . i. . 252

- Dantis Tenebræ . . . . . . . i. . 299

- Beauty and the Bird . . . . . . i. . 286

- A Match with the Moon . . . . . i. . 287

-

-

Sonnets for Pictures, and other

Sonnets,

continued:

- Autumn Idleness . . . . . . . i. . 211

- Farewell to the Glen . . . . . . i. . 219

- The Monochord . . . . . . . i. . 216

-

-

- 2b.âContents of

Poems, 1881.

-

-

Poems:

-

[This section contains the same compositions as the section Poems

in the volume of 1870, but in a different sequence, and also the fol-

lowing] - Down Stream . . . . . . . i. . 319

- Wellington's Funeral . . . . . . i. . 281

- World's Worth . . . . . . . i. . 250

- The Bride's Prelude . . . . . . i. . 35

-

[But the following are removed to a section headed]

-

-

-

Lyrics:

- A New Year's Burden . . . . . . i. . 296

- Even So . . . . . . . . . i. . 297

-

[In other respects the section Lyrics consists of the Songs which used

to form part of âThe House of Life.â]

-

-

Sonnets:

-

[Contains the various compositions which appeared in the volume

of 1870 under the heading Sonnets for Pictures, and other Sonnets,

except St. Luke the Painter, Lilith, Sibylla Palmifera, Autumn Idleness,

Farewell to the Glen, and The Monochord; these six sonnets were

transferred to The House of Life in the Ballads and Sonnets (3),

the Lilith and Sibylla Palmifera being renamed Body's Beauty and

Soul's Beauty.]

-

-

-

Translations:

-

[Contains the six translations which in the volume of 1870 appeared

under the heading âPoems,â the title One Girl being now superseded by

the title Beauty (Sappho); also the following] - Youth and Lordship (Italian Street-song) . . i. . 366

- The Leaf (Leopardi) . . . . . . ii. . 409

- Francesca da Rimini (Dante) . . . . ii. . 405

-

-

-

- 3.âContents of

Ballads and Sonnets.

-

-

Ballads:

- Rose Mary . . . . . . . . i. . 103

- The White Ship . . . . . . . i. . 137

- The King's Tragedy . . . . . . i. . 148

- The House of Lifeâ A Sonnet Sequence. . . i. . 176

-

-

Lyrics &c:

- Soothsay . . . . . . . . i. . 334

- Chimes . . . . . . . . . i. . 330

- Parted Presence . . . . . . . i. . 324

- A Death-parting . . . . . . . i. . 322

- Spheral Change . . . . . . . i. . 326

- Sunset Wings . . . . . . . i. . 316

- Song and Music . . . . . . . i. . 253

- Three Shadows . . . . . . . i. . 321

- Alas so long! . . . . . . . . i. . 327

- Adieu . . . . . . . . . i. . 333

- Insomnia . . . . . . . . i. . 328

- Possession . . . . . . . . i. . 329

- The Cloud Confines . . . . . . i. . 317

-

-

Sonnets:

- For the Holy Family, by Michelangelo . . . i. . 351

- For Spring, by Sandro Botticelli . . . . i. . 352

- Five English Poets . . . . . . i. . 337

- Tiber, Nile, and Thames . . . . . i. . 340

- The Last Three from Trafalgar . . . . i. . 342

- Czar Alexander II. . . . . . . i. . 342

- Words on the Window-pane . . . . i. . 299

- Winter . . . . . . . . . i. . 341

- Spring . . . . . . . . . i. . 323

- The Church Porch . . . . . . . i. . 272

- Untimely Lost (Oliver Madox Brown) . . . i. . 323

-

-

Sonnets, continued:

- Place de la Bastille, Paris . . . . . i. . 261

- âFoundâ (for a Picture) . . . . . i. . 363

- A Sea-spell . . . . . . . . i. . 361

- Fiammetta . . . . . . . . i. . 362

- The Day-dream . . . . . . . i. . 364

- Astarte Syriaca . . . . . . . i. . 361

- Proserpina (Italian and English) . . . . i. . 370

- La Bella Mano â . . . . i. . 372

Note: Broken type: In the seventh line, the dot of the "i" for the page number is missing. -

GABRIEL ROSSETTI DURING HIS LIFETIME.

Â

2a, 2b, and 3. The dedication to 1b appears in its

proper place.

- 1a.â

The Early Italian

Poets:

Whatever is mine in this book is inscribed to my Wife.â

D.G.R. 1861. - 2a.â

Poems,

1870:

To William Michael Rossetti, these Poems, to so many

of which, so many years back, he gave the first brotherly

hearing, are now at last dedicated. - 2b.â

Poems,

1881:

Same dedication, adding the dates â1870â1881.â - 3.â

Ballads and Sonnets:

To Theodore Watts, the Friend whom my verse won for

me, these few more pages are affectionately inscribed.

tisementâ:

ââMany poems in this volume were written

between 1847

and 1853. Others are of recent date, and a few

belong to

the intervening period. It has been thought

unnecessary

to specify the earlier work, as nothing is included

which

the author believes to be immature.â

âThe above brief note was prefixed to these poems

when

first published in 1870. They have now been for some

time

out of print.

âThe fifty sonnets of the

House of Life, which first appeared

here, are now embodied with the

full series in the volume

entitled

Ballads and Sonnets.

âThe fragment of

The Bride's Prelude, now first printed,

was written very early, and is here

associated with other

work of the same date; though its

publication in an un-

finished form needs some

indulgence.â

Â

the âPoems published by Rossetti during his Lifetimeâ

with the contents of the present Collected Works,

section Poems, it will be found that the following

compositions are new. I put an asterisk against the

titles of the few which had been printed by my

brother in some outlying form, but not in his volumes.

For any further particulars the reader may be referred

to my notes.

- At the Sun-rise in 1848 . . . . . . . 237

- *Autumn Song . . . . . . . . 237

- The Lady's Lament . . . . . . . . 238

- A Trip to Paris and Belgium . . . . . . 255

- The Staircase of Notre Dame, Paris . . . . 261

- Near BrusselsâA Half-way Pause . . . . . 262

- *Antwerp and Bruges . . . . . . . 263

- On Leaving Bruges . . . . . . . . 264

- Vox Ecclesiæ, Vox Christi . . . . . . 265

- The Mirror . . . . . . . . . 272

- During Music . . . . . . . . . 273

- *On the Site of a Mulberry-tree, etc. . . . . 285

- *On certain Elizabethan Revivals . . . . . 285

- English May . . . . . . . . . 286

- Dawn on the Night-journey . . . . . . 303

- To Philip Bourke Marston . . . . . . 340

- *Raleigh's Cell in the Tower . . . . . . 341

- For an Annunciation . . . . . . . 343

- *For a Virgin and Child by Memmelinck . . . 348

- *For a Marriage of St. Catherine, by the same . . 349

- *Mary's Girlhood, No. 2 . . . . . . . 354

- Michael Scott's Wooing . . . . . . . 357

- Mnemosyne . . . . . . . . . 362

- La Ricordanza (Memory) . . . . . 370-1

- Con manto d'oro, etc. (With golden mantle, etc.) . 372-3

- Robe d'or, etc. (A golden robe, etc.) . . . 372-3

- Barcarola . . . . . . . . . . 374

- Barcarola . . . . . . . . . . 375

- Bambino Fasciato . . . . . . . . 375

- Thomæ Fides . . . . . . . . . 376

- Versicles and Fragments . . . . . 377-80

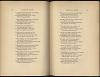

- Yea, thou shalt learn how salt his food who fares

- Upon another's bread,âhow steep his path

- Who treadeth up and down another's stairs.

- Behold, even I, even I am Beatrice.

- Of Florence and of Beatrice

- Servant and singer from of old,

- O'er Dante's heart in youth had toll'd

- The knell that gave his Lady peace;

- And now in manhood flew the dart

- Wherewith his City pierced his heart.

- Yet if his Lady's home above

- Was Heaven, on earth she filled his soul;

- And if his City held control

- 10 To cast the body forth to rove,

- The soul could soar from earth's vain throng,

- And Heaven and Hell fulfil the song.

- Follow his feet's appointed way;â

- But little light we find that clears

- The darkness of the exiled years.

- Follow his spirit's journey:ânay,

- What fires are blent, what winds are blown

- On paths his feet may tread alone?

- Yet of the twofold life he led

- 20 In chainless thought and fettered will

- Some glimpses reach us,âsomewhat still

- Of the steep stairs and bitter bread,â

- Of the soul's quest whose stern avow

- For years had made him haggard now.

- Alas! the Sacred Song whereto

- Both heaven and earth had set their hand

- Not only at Fame's gate did stand

- Knocking to claim the passage through,

- But toiled to ope that heavier door

- 30 Which Florence shut for evermore.

- Shall not his birth's baptismal Town

- One last high presage yet fulfil,

- And at that font in Florence still

- His forehead take the laurel-crown?

- O God! or shall dead souls deny

- The undying soul its prophecy?

- Aye, 'tis their hour. Not yet forgot

- The bitter words he spoke that day

- When for some great charge far away

- 40 Her rulers his acceptance sought.

- âAnd if I go, who stays?ââso rose

- His scorn:ââand if I stay, who goes?â

- âLo! thou art gone now, and we stayâ:

- (The curled lips mutter): âand no star

- Is from thy mortal path so far

- As streets where childhood knew the way.

- To Heaven and Hell thy feet may win,

- But thine own house they come not in.â

- Therefore, the loftier rose the song

- 50 To touch the secret things of God,

- The deeper pierced the hate that trod

- On base men's track who wrought the wrong;

- Till the soul's effluence came to be

- Its own exceeding agony.

- Arriving only to depart,

- From court to court, from land to land,

- Like flame within the naked hand

- His body bore his burning heart

- That still on Florence strove to bring

- 60 God's fire for a burnt offering.

- Even such was Dante's mood, when now,

- Mocked for long years with Fortune's sport,

- He dwelt at yet another court,

- There where Verona's knee did bow

- And her voice hailed with all acclaim

- Can Grande della Scala's name.

- As that lord's kingly guest awhile

- His life we follow; through the days

- Which walked in exile's barren ways,â

- 70 The nights which still beneath one smile

- Heard through all spheres one song increase,â

- âEven I, even I am Beatrice.â

- At Can La Scala's court, no doubt,

- Due reverence did his steps attend;

- The ushers on his path would ben

- At ingoing as at going out;

- The penmen waited on his call

- At council-board, the grooms in hall.

- And pages hushed their laughter down,

- 80 And gay squires stilled the merry stir,

- When he passed up the dais-chamber

- With set brows lordlier than a frown;

- And tire-maids hidden among these

- Drew close their loosened bodices.

- Perhaps the priests, (exact to span

- All God's circumference,) if at whiles

- They found him wandering in their aisles,

- Grudged ghostly greeting to the man

- By whom, though not of ghostly guild,

- 90 With Heaven and Hell men's hearts were fill'd.

- And the court-poets (he, forsooth,

- A whole world's poet strayed to court!)

- Had for his scorn their hate's retort.

- He'd meet them flushed with easy youth,

- Hot on their errands. Like noon-flies

- They vexed him in the ears and eyes.

- But at this court, peace still must wrench

- Her chaplet from the teeth of war:

- By day they held high watch afar,

- 100 At night they cried across the trench;

- And still, in Dante's path, the fierce

- Gaunt soldiers wrangled o'er their spears.

- But vain seemed all the strength to him,

- As golden convoys sunk at sea

- Whose wealth might root out penury:

- Because it was not, limb with limb,

- Knit like his heart-strings round the wa l

- Of Florence, that ill pride might fall.

- Yet in the tiltyard, when the dust

- 110 Cleared from the sundered press of knights

- Ere yet again it swoops and smites,

- He almost deemed his longing must

- Find force to yield that multitude

- And hurl that strength the way he would.

- How should he move them,âfame and gain

- On all hands calling them at strife?

- He still might find but his one life

- To give, by Florence counted vain:

- One heart the false hearts made her doubt,

- 120 One voice she heard once and cast out.

- Oh! if his Florence could but come,

- A lily-sceptred damsel fair,

- As her own Giotto painted her

- On many shields and gates at home,â

- A lady crowned, at a soft pace

- Riding the lists round to the dais:

- Till where Can Grande rules the lists,

- As young as Truth, as calm as Force,

- She draws her rein now, while her horse

- 130 Bows at the turn of the white wrists;

- And when each knight within his stall

- Gives ear, she speaks and tells them all:

- All the foul tale,âtruth sworn untrue

- And falsehood's triumph. All the tale?

- Great God! and must she not prevail

- To fire them ere they heard it through,â

- And hand achieve ere heart could rest

- That high adventure of her quest?

- How would his Florence lead them forth,

- 140 Her bridle ringing as she went;

- And at the last within her tent,

- 'Neath golden lilies worship-worth,

- How queenly would she bend the while

- And thank the victors with her smile!

- Also her lips should turn his way

- And murmur: âO thou tried and true,

- With whom I wept the long years through!

- What shall it profit if I say,

- Thee I remember? Nay, through thee

- 150 All ages shall remember me.â

- Peace, Dante, peace! The task is long,

- The time wears short to compass it.

- Within thine heart such hopes may flit

- And find a voice in deathless song:

- But lo! as children of man's earth,

- Those hopes are dead before their birth.

- Fame tells us that Verona's court

- Was a fair place. The feet might still

- Wander for ever at their will

- 160 In many ways of sweet resort;

- And still in many a heart around

- The Poet's name due honour found.

- Watch we his steps. He comes upon

- The women at their palm-playing.

- The conduits round the gardens sing

- And meet in scoops of milk-white stone,

- Where wearied damsels rest and hold

- Their hands in the wet spurt of gold.

- One of whom, knowing well that he,

- 170 By some found stern, was mild with them,

- Would run and pluck his garment's hem,

- Saying, âMesser Dante, pardon me,ââ

- Praying that they might hear the song

- Which first of all he made, when young.

- âDonne che aveteâ* . . . Thereunto

- Thus would he murmur, having first

- Drawn near the fountain, while she nurs'd

- His hand against her side: a few

- Sweet words, and scarcely those, half said:

- 180 Then turned, and changed, and bowed his head.

* Donne che avete intelletto

d'amore:âthe first canzone of

the Vita Nuova.

- For then the voice said in his heart,

- âEven I, even I am Beatrice;â

- And his whole life would yearn to cease:

- Till having reached his room, apart

- Beyond vast lengths of palace-floor,

- He drew the arras round his door.

- At such times, Dante, thou hast set

- Thy forehead to the painted pane

- Full oft, I know; and if the rain

- 190 Smote it outside, her fingers met

- Thy brow; and if the sun fell there,

- Her breath was on thy face and hair.

- Then, weeping, I think certainly

- Thou hast beheld, past sight of eyne,â

- Within another room of thine

- Where now thy body may not be

- But where in thought thou still remain'st,â

- A window often wept against:

- The window thou, a youth, hast sought,

- 200 Flushed in the limpid eventime,

- Ending with daylight the day's rhyme

- Of her; where oftenwhiles her thought

- Held theeâthe lamp untrimmed to writeâ

- In joy through the blue lapse of night.

- At Can La Scala's court, no doubt,

- Guests seldom wept. It was brave sport,

- No doubt, at Can La Scala's court,

- Within the palace and without;

- Where music, set to madrigals,

- 210 Loitered all day through groves and halls.

- Because Can Grande of his life

- Had not had six-and-twenty years

- As yet. And when the chroniclers

- Tell you of that Vicenza strife

- And of strifes elsewhere,âyou must not

- Conceive for church-sooth he had got

- Just nothing in his wits but war:

- Though doubtless 'twas the young man's joy

- (Grown with his growth from a mere boy,)

- 220To mark his âViva Cane!â scare

- The foe's shut front, till it would reel

- All blind with shaken points of steel.

- But there were placesâheld too sweet

- For eyes that had not the due veil

- Of lashes and clear lidsâas well

- In favour as his saddle-seat:

- Breath of low speech he scorned not there

- Nor light cool fingers in his hair.

- Yet if the child whom the sire's plan

- 230 Made free of a deep treasure-chest

- Scoffed it with ill-conditioned jest,â

- We may be sure too that the man

- Was not mere thews, nor all content

- With lewdness swathed in sentiment.

- So you may read and marvel not

- That such a man as Danteâone

- Who, while Can Grande's deeds were done,

- Had drawn his robe round him and thoughtâ

- Now at the same guest-table far'd

- 240 Where keen Uguccio wiped his beard.*

- Through leaves and trellis-work the sun

- Left the wine cool within the glass,â

- They feasting where no sun could pass:

- And when the women, all as one,

- Rose up with brightened cheeks to go,

- It was a comely thing, we know.

* Uguccione della Faggiuola, Dante's former protector, was

now his fellow-guest at Verona.

- But Dante recked not of the wine;

- Whether the women stayed or went,

- His visage held one stern intent:

- 250 And when the music had its sign

- To breathe upon them for more ease,

- Sometimes he turned and bade it cease.

- And as he spared not to rebuke

- The mirth, so oft in council he

- To bitter truth bore testimony:

- And when the crafty balance shook

- Well poised to make the wrong prevail,

- Then Dante's hand would turn the scale.

- And if some envoy from afar

- 260 Sailed to Verona's sovereign port

- For aid or peace, and all the court

- Fawned on its lord, âthe Mars of war,

- Sole arbiter of life and death,ââ

- Be sure that Dante saved his breath.

- And Can La Scala marked askance

- These things, accepting them for shame

- And scorn, till Dante's guestship came

- To be a peevish sufferance:

- His host sought ways to make his days

- 270 Hateful; and such have many ways.

- There was a Jester, a foul lout

- Whom the court loved for graceless arts;

- Sworn scholiast of the bestial parts

- Of speech; a ribald mouth to shout

- In Folly's horny tympanum

- Such things as make the wise man dumb.

- Much loved, him Dante loathed. And so,

- One day when Dante felt perplex'd

- If any day that could come next

- 280 Were worth the waiting for or no,

- And mute he sat amid their din,â

- Can Grande called the Jester in.

- Rank words, with such, are wit's best wealth.

- Lords mouthed approval; ladies kept

- Twittering with clustered heads, except

- Some few that took their trains by stealth

- And went. Can Grande shook his hair

- And smote his thighs and laughed i' the air.

- Then, facing on his guest, he cried,â

- 290 âSay, Messer Dante, how it is

- I get out of a clown like this

- More than your wisdom can provide.â

- And Dante: â'Tis man's ancient whim

- That still his like seems good to him.â

- Also a tale is told, how once,

- At clearing tables after meat,

- Piled for a jest at Dante's feet

- Were found the dinner's well-picked bones;

- So laid, to please the banquet's lord,

- 300 By one who crouched beneath the board.

- Then smiled Can Grande to the rest:â

- âOur Dante's tuneful mouth indeed

- Lacks not the gift on flesh to feed!â

- âFair host of mine,â replied the guest,

- âSo many bones you'd not descry

- If so it chanced the dog were I.â*

* â

Messere, voi non vedreste tant 'ossa se cane io

fossi

.â The

point of the reproach is difficult

to render, depending as it does on

the literal meaning of the

name

Cane.

- But wherefore should we turn the grout

- In a drained cup, or be at strife

- From the worn garment of a life

- 310 To rip the twisted ravel out?

- Good needs expounding; but of ill

- Each hath enough to guess his fill.

- They named him Justicer-at-Law:

- Each month to bear the tale in mind

- Of hues a wench might wear unfin'd

- And of the load an ox might draw;

- To cavil in the weight of bread

- And to see purse-thieves gibbeted.

- And when his spirit wove the spell

- 320 (From under even to over-noon

- In converse with itself alone,)

- As high as Heaven, as low as Hell,â

- He would be summoned and must go:

- For had not Gian stabbed Giacomo?

- Therefore the bread he had to eat

- Seemed brackish, less like corn than tares;

- And the rush-strown accustomed stairs

- Each day were steeper to his feet;

- And when the night-vigil was done,

- 330 His brows would ache to feel the sun.

- Nevertheless, when from his kin

- There came the tidings how at last

- In Florence a decree was pass'd

- Whereby all banished folk might win

- Free pardon, so a fine were paid

- And act of public penance made,â

- This Dante writ in answer thus,

- Words such as these: âThat clearly they

- In Florence must not have to say,â

- 340The man abode aloof from us

- Nigh fifteen years, yet lastly skulk'd

- Hither to candleshrift and mulct.

- âThat he was one the Heavens forbid

- To traffic in God's justice sold

- By market-weight of earthly gold,

- Or to bow down over the lid

- Of steaming censers, and so be

- Made clean of manhood's obloquy.

- âThat since no gate led, by God's will,

- 350 To Florence, but the one whereat

- The priests and money-changers sat,

- He still would wander; for that still,

- Even through the body's prison-bars,

- His soul possessed the sun and stars.â

- Such were his words. It is indeed

- For ever well our singers should

- Utter good words and know them good

- Not through song only; with close heed

- Lest, having spent for the work's sake

- 360 Six days, the man be left to make.

- Months o'er Verona, till the feast

- Was come for Florence the Free Town:

- And at the shrine of Baptist John

- The exiles, girt with many a priest

- And carrying candles as they went,

- Were held to mercy of the saint.

- On the high seats in sober state,â

- Gold neck-chains range o'er range below

- Gold screen-work where the lilies grow,â