PRE-RAPHAELITISM

AND THE

PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD

Â

Â

Sir W. B. Richmond, K.C.]

W. HOLMAN-HUNT

Pre-Raphaelitism and

the Pre-Raphaelite

Brotherhood

By

W. HOLMAN-HUNT, O.M., D.C.L.

SECOND EDITON

REVISED FROM THE AUTHOR'S NOTES BY M. E. H.-H.

TWO VOLUMES

Vol. II

WITH 208 ILLUSTRATIONS

New York

E. P. Dutton & COMPANY

681 FIFTH AVENUE

1914

Â

Â

Note: The word âPageâ appears as a running header over the page

numbers.

-

CHAPTER I

Lord and Lady Napier and Frederick LockwoodâVisit the caverns beneath

Jerusalemâ

Letter from D. G. RossettiâKaimil

PashaâSir Moses MontefioreâDuke of Brabantâ

Visit

to the mosqueâMax and the pistolâContention with the bishop

concerning Arab

convertsâLetter from MillaisâJerusalem

ladies come to see my pictureâSend âScapeâ

goatâ to

EnglandâMoonlight over the city. . . . . . . . . 1

-

CHAPTER II

An honest Jewish convertâStory of the mercerâVisit Levi's

houseâThe retributionâ

âSelectionâ in

ArtâWarder CressenâWaterâcolour of

GihonâSuccumb to feverâ

Visit the mosqueâSend

pictures to OxfordâJourney to Nazareth, Tiberias, Lake of

Merom, and

Mount HermonâSyrian landscapeâCountry between Tabor and

Tiberiasâ

Guide and Issa converse about my faithâTents

pitched on burialâgroundâCholera

ragingâMoonlight

on Tiberiasâ

Mukary refuses to stayâThe spring

of Capernaumâ

SafidâGraham departs westward. . . . . . . . .

. . 16

-

CHAPTER III

Plain of MeromâIssa is not appreciating the scene, feels his

superiorityâCæsarea Philippiâ

Ancient

remainsâMoslem boy lostâHasbeyaâDar al

AkmarâDamascusâConsulâ

General Sir Henry

WoodâLady

EllenboroughâZebedeenâBaalbecâTempleâA

primiâ

tive hotelâUnconscious actor to delighted

audienceâAscend LebanonâZahleâReach

Beyrout and

part with IssaâTake ship to Constantinople for the

CrimeaâCholera and

mutiny on boardâArrive at Crimea. . . .

. . . . . . 36

-

CHAPTER IV

Marseilles to ParisâMike HallidayâFebruary

1856âHalliday and I take house togetherâ

Disintegration fo

the BrotherhoodâRossetti in OxfordâMiss

SiddalâChristina

Rossetti's sonnet on the P.R.B.âWoolner's

return from AustraliaâSeveral artists

working on our

linesâMadox Brown steadfastly doing soâAnnual prizes at

Liverpoolâ

Arthur HughesâMillais and

RuskinâMillais' marriageâVisit

OxfordââPotâboilersââ

Small

âEve of St. Agnesâ sold to Mr.

MillerâGambart treats for copyright of âLight

of the WorldââCopyright in

England and FranceâFord Madox Brown paints direct

from

NatureâExhbition in Charlotte StreetâIllustrations to

TennysonâRossetti's

designsâThe volume a commercial

failureâMenzel's workââScapegoatââMillais brings

his picture

to LondonâRuskinâJohn Luard's first pictureâMillais'

âPeaceâ and

âBurning LeavesââGambart's strictures on

the âScapegoatââCriticisms

on the picture

in

The Times, etc.âFurther comments in

the Press on P.R.B. picutres. . . 59

-

CHAPTER V

LeightonâWork at Claredon Press, OxfordâThackerary stands for

ParliamentâHis visit

to Mr. CombeâLetters from

MillaisâMr. Combe persuades me to become a candidate

for R.A.

AssociateshipâEnrolled myself for winter

electionâWattsâMiss Emma

BrandlingâLittle Holland

HouseâWoolnerâTennyson at

RoehamptonâTennyson

demurs to my illustrationsâRobert and

Mrs. BrowningâDeath of my fatherâSeddonâ

Take

Hook's house on Campden HillâLady Goderich's

dinnerâpartyâSir Colin Campbell

and

CarlyleâWoodward and the Oxford MuseumâDecoration of the Union,

Oxfordâ

First meeting with BurneâJonesâFitting up

my house at KensingtonâBachelor parties

at Henry Vaux'sâThe

Academy rejects me. . . . . . . . 86

-

CHAPTER VI

The Hogarth ClubâLeighton and a Royal CommissionâMrs. Combe and

Mrs. Collinsâ

Completion of my âTempleâ pictures continually

delayedâArthur Lewis's social

gatheringsâFred

WalkerâMr. and Mrs. George Grove and Mr. and Mrs.

Phillipsâ

Millais exhibits âSir

IsumbrasââTom Taylor's imitation of ancient

balladâRuskin's

denunciation of the pictureâCharles Reade

buys itâFrederick Sandy's caricatureâ

Mr. and Mrs. Combe

visit Brown's studioâLetter from Brown about

CarlyleâOxford

MuseumâO'SheaâManchester loan

exhibitionâConversation with Sir Thomas Fairbairn

about

WoolnerâWoolner and his workâRossetti avoids Millais and

myselfâRuskin's

appreciation of Rossetti's powerâMr. and

Mrs. Thoby PrincepâTennyson and

ThackerayâRemonstrances on

my âidlenessâ from unknown correspondents . . 111

-

CHAPTER VII

Visit to TennysonâHis page boyâDistress at

criticsâNational support of ArtâMillaisâ

early

geniusâGeorge Leslie delivers his father's dying messageâG. F.

Wattsâ

Thornbury's criticism in the

Anthenæum on P.R.B.âismâMr. and Mrs. Combe

at

OxfordâSt. Barnabas ChurchâUniversity

PressâConference on ways and meansâOur

relations with

DickensâWilkie CollinsâHis roomâVisit to Charles

Dickens in Tavistock

SquareâThe Duchess of ArgyllâSir C.

EastlakeâGambart's treatment of my terms for

the âTempleâ pictureâIt goes to

WindsorâChat with Thackeray at Cosmopolitan

ClubâIntroduce

Woolner at Oxford. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

-

CHAPTER VIII

Breakfast with GladstoneâThe Rev. Joseph WolfâI discuss the

merit of Dresden chinaâ

Walking tour in 1860 with Tennyson, Palgrave,

Woolner, and Val PrinsepâGad's Hillâ

Charles Collins marries

Kate Dickens, 1861âHis views on the merits of a good

tailorâ

Morris's business formedâPoynter's picture âFaithful unto DeathââInjury

from fire

to my âTempleâ

pictureâPortrait of Judge LushingtonâHis storiesâ1862

Exhibititionâ

Prince Consort's deathâWoolner. . . . . . . . .

. . 153

-

CHAPTER IX

Jacob Omnium controversy in the

TimesâDeath of Augustus

EggâLetter from Charles

DickensâVisit to Sir Thomas

FairbairnâWingrove CookâConversation about

ThackerayâTrelawnyâGeorge MeredithâProposal for

George Meredith to live with

D.G. RosettiâMarriage of the Prince of

WalesâVisit to the Prince and Princess of

Wales to my

exhibitionâGaribaldi's visit to EnglandâBaron

LysâBreakfast at the

Duchess of Argyll'sâJohn Tupper as art

masterâRoyal Academy efforts to pacify

malcontentsâG. F.

Watts. . . . . . . . . . . . 176

-

CHAPTER X

W. Beamont and St. Michael's, CambridgeâDelay in returning to the

EastâMy marriageâ

âThe

Festival of St. SwithinââFred WalkerâMy

bank stop paymentâStart for the

EastâCholera prevailing at

MarseillesâQuarantineâGo to FlorenceââIsabella and

the Pot of

BasilââDeath of my wifeâReturn to

EnglandâThe home of Charles

DickensâMy election to the

Athenæum ClubâReturn to Florence to complete my wife's

tombâMeet Ruskin in VeniceâConversation with Ruskin. . . . . .

196

-

CHAPTER XI

I visit RomeâTake ship at Naples for SyriaâCommence âShadow of DeathââDar

Berruk

DarâBethlehemâThe Crown Prince of

PrussiaâNazarethâCanaâCaptain

Luardâ

Ride to Jerusalem with news of FrancoâGerman

WarâFeverâVisit Pasha in

Armenian

churchâLibeation of EzaakâFinish my

pictureâVisitors in vainâParis after the

German

WarâPicture arrives in LondonâMillais in vain urges me to put

down my

name again for the AcademyâCommission from Queen

VictoriaâElizabeth Thompsonâ

Briton Rivière. . .

. . . . . . . . . . . 219

-

CHAPTER XII

TissotâCharles Collin's deathâMy second marriageâWe

travel to JerusalemâMeeting with

Lieutenant

KitchenerâTrouble from non-arrival of casesââThe ShipââThe âInnoâ

centsââTo

AscalonâGo south to paint backgroundâNew studioâVisit

of the

Mahomedan ladiesâExpedition to Jordan and Dead

SeaâSend family to take refuge in

Greek convent at JaffaâI

remain in JerusalemâAfter two and a half years return with

partly

finished paintingâThe Grosvenor GalleryâR. Browning and

VelasquezâSir R.

Owen's portraitââAmaryllisâââMiss FlamboroughââRobert

BrowningâHis sonâ

Browning and D.G.

RossettiâVisit to my old studio in ChelseaâTyphoid

feverâ

Sir William GullâMillais advises me to have the

picure relinedâI buy a house at

FulhamâRuskin's visit

thereâHis Oxford lectureâAbandon Jerusalem âInnocentsââ

Recommence on new

canvasâIllnessâFinish the pictureâExhibition of my

works at

âFine Artsâ Society. . . . . . . . . . . . .

249

-

CHAPTER XIII

LawlessâF. WalkerâPhilip CalderonâWalter

CraneââThe Triumph of the

Innocentsââ

Acquired by

LiverpoolââChrist among the

DoctorsââD.G. Rossetti's

deathâArticles

in

ContemporaryâAddress at

Rossetti's fountainâMadox

BrownâWhistlerâH.

HerkomerâF.

ShieldsâRev. E. YoungâRossetti's workâE.

BurneâJonesâGilbert

and Sullivan's

Patience and those satirisedâE. R. HughesâCecil

LawsonâJohn Brettâ

âThe Bride

of BethlehemâââSorrowââMillais made a

baronetâHe talks of the early

P.R.B. daysâMillais and I walk

to see Charles KeaneâThe Bishop's moatâArtist's

materials. .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . 285

-

CHAPTER XIV

Commence âThe Lady of

ShalottâââMay

MorningââLast meeting with Mrs.

Combeâ

Her deathâJourney through Italy, Greece, Egypt to the

EastâIllustrations to Sir Edwin

Arnold's

Light of the WorldâThe Miracle of âHoly

FireââW. B. Scott's deathâ

Banquet at

GuildhallâMadox Brown's positionâLeigton's

deathâMillaisâ deathâ

William Morris'

deathâBurneâJones' styleâMy portrait by W. B.

Richmond presented to

meâLast talk with WattsâThe

University of Oxford bestows the degree of D.C.L. upon

meâKing Edward

VII confers upon me the Order of MeritâReflections on our

course

âNationality in artâForeign

artâMillaisâ picturesâThe sale room no test of

meritâ

Educational activity injurious rather than beneficial to the

nation's art. . . . 308

-

CHAPTER XV

Retrospect

W. Morris and Co.âWilliam de MorganâControversy about

leadership of the P.R.B.â

W. Rossetti's sonnets in

The

Germ

âMonsieur Sizeranne's letterâMr. Cook's

handâ

bookâExtracts from William RossettiâThe

genesis of D.G. Rossetti's picture

âFoundâ

ââThe Awakened

ConscienceââF.M. Brown's diaryâThe meaning

of the word

Pre-RaphaeliteâF. G. Stephens, W. Sharp, W. Bell Scott. . .

. 335

-

CHAPTER XVI

Retrospect (

continued)

The delusions of our interpreters. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 353

-

CHAPTER XVII

Retrospect (

concluded)

Art and its national qualityâJournalismâLord Leighton's

warningâArt the handmaid of

moralityâArt is

loveâForeign academiesâImpressionismâAmerican

students in Parisâ

Effect of civil wars on English artâThe

rise of portrait painting in

EnglandâConstable's

prophecyââBacchus and AriadneââCopyright

lawsâWhat a people is led to admire,

that it will

becomeâLeonardo da Vinci speaksâSlavish idolatry not

reverenceâThe

great days of Italian artâWant of undersanding

leads to unrestrained utterancesâ

The responsibility of the

PressâThe purpose of the art. . . . . . . . 358

-

Last Notes by the Editor. . . . . . . . . . . . 380

-

Appendix. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 385

-

Index. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 435

Â

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Note: The word âPageâ appears as a running header over the page

numbers.

-

Portrait of W. Holman-Hunt . . . . By Sir W. B. Richmond, K.C.

(

Frontispiece)

-

Royal Group, including Kaimil Pasha . . . . . . . . . 4

-

The Mueddin calling to Prayer. . . . . By W. H. H. . . 14

-

Study of Jew . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 18

-

Examples of Jewish Type . . . . . . .âW. H. H. . . 19

-

The Plain of Rephaim . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 24

-

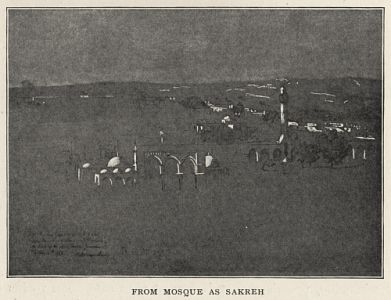

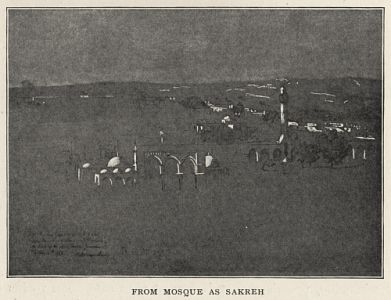

From the Mosque As Sakreh . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 26

-

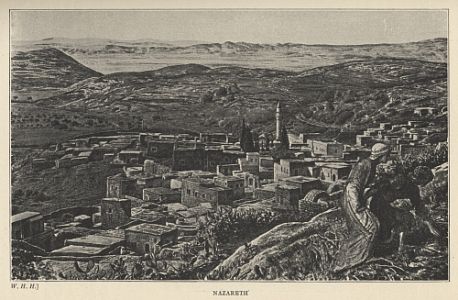

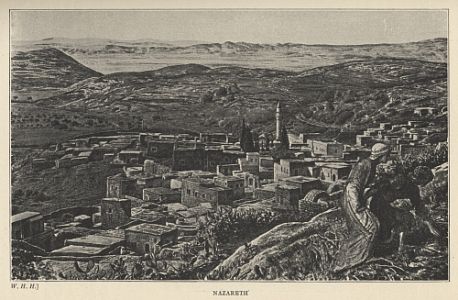

Nazareth. . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 27

-

Jenin . . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 28

-

Lake of Tiberias . . . . . . . . . âA. Hughes . . 33

(

From a sketch by W. H. H.)

-

The Jordan . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 37

-

Hasbeya . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 43

-

Ruins of Baalbec. . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 47

(

The property of Mrs. Tristram and Valentine)

-

Temple of Baalbec . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 48

-

Zahle . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 53

-

Constantinople . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 54

-

Smyrna Roadstead . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 54

-

Portrait of Captain Pigeon . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 55

-

Two Youthful Designs to Leigh Hunt's Poem . . âW. H. H. . . 56

-

Two Later Designs to the Same . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 57

-

Rough Sketch for Nativity . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 58

-

The Cemetary, Pera . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 60

(

The property of Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

-

Death of Chatterton . . . . . . . . âHenry Wallis . . 62

-

April Love . . . . . . . . . . âA. Hughes . . 63

-

The Sailor Boy's Return . . . . . . . âA. Hughes . . 64

-

Portrait of Arthur Huges . . . . . . âA. Hughes . . 64

-

Morning Prayer . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 68

(

The property of A. F. Jarrow, Esq.)

-

Two Designs for Cophetua . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 70, 71

-

Five Lady of Shalott Designs . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 72-74

-

Two Haroun al Raschid Designs . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 75, 76

-

Lady Godiva Design . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 77

-

Three Oriana Designs . . . . . . . . By W. H. H. . . 78, 79

-

Portrait of F. Leighton . . . . . By Sir F. Leighton, Bart. 87

(

The property of Hon. Lady Leighton-Warren)

-

Portrait of W. Holman-Hunt . . . . . . . . . . . 91

-

Portrait of G. F. Watts . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

-

Portrait of Miss Emma Brandling . . . . . By G. F. Watts . . 93

(

The property of Mrs. Holman-Hunt)

-

Medallion of Tennyson . . . . . . . . . . â T. Woolner . . 94

-

Portrait of Tennyson . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

-

Cophetua and The Beggar Maid . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 96

-

Portrait of Robert Browning . . . . . . . . . . . 97

-

Portrait of Mrs. Browning . . . . . . . âField Talfourd . . 97

-

Portrait of Lady Goderich . . . . . . âJ. E. Millais . . 99

-

Portrait of Sir Colin Campbell . . . . . . . . . . 100

-

Portrait of Carlyle . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

-

Portrait of Henry VIII . . . . . . . âHolbein. . . 102

-

Portrait of Spencer Stanhope . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 103

(

The property of the Earl of Carnarvon)

-

Portrait of Woodward . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

-

Portrait of William Morris . . . . . . . . . . . 103

-

Portrait of Swinburne . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

-

Portrait of E. Burne-Jones . . . . . . . . . . . 104

-

Portrait of William Rivière . . . . . . . . . . . 105

-

Portrait of Briton Rivière . . . . . . . . . 105

-

Chairs Designed by W. H. H. . . . . . . . . . . . 106

-

King of Hearts . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H.. . 107

-

Will-oâ-the-Wisp . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H.. . 115

-

Parting . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H.. . 116

-

The Lent Jewel . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H.. . 117

-

Invitation Card . . . . . . . . . âF. Walker. . 118

-

Portrait of Federick Walker . . . . . âF. Walker. . 118

-

Another Invitation Card . . . . . . . âF. Walker. . 118

-

Portrait of W. B. Richmond . . . . By Sir W. B. Richmond, K.C.B. 119

-

John Ruskin and Dr. Acland . . . . . . . . . . . 123

-

Portrait of Sir Henry Taylor . . . . . . . . . . . 130

-

Portrait of Lady Tennyson . . . . . . By G. Floater. . 133

-

Portrait of Thomas Combe . . . . . . âW. H. H.. . 140

-

Portrait of Mrs. Combe . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H.. . 141

-

Portrait of Charles Dickens . . . . . . . . . 145

-

Portrait of Thackeray . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

-

Portrait of the Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone . . . . . . . 154

-

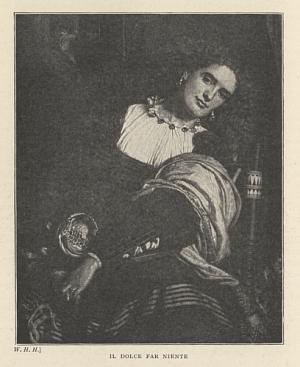

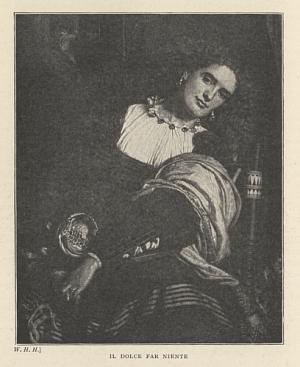

Il dolce far niente . . . . . . . . âW. H. H.. . 156

(

The property of T. Brocklebank, Esq.)

-

The Land's End . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

-

Portrait of F. T. Palgrave . . . . . . . . . . . 158

-

Portrait of Tennyson in his Cloak . . . . . . . . . 159

-

Portrait of Val Prinsep . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

-

Portrait of Tennyson . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

-

Helston, Cornwall . . . . . . . . By W. H. H.. . 161

-

Miss Caroline Fox . . . . . . . â G. F. Watts . 165

-

Gad's Hill Place . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

-

Portrait of Dickens . . . . . . . . . . .. . 167

-

Portrait of Edward J. Poynter . . . . . . . . . . 169

-

âFaithful unto Deathâ . . . . By Sir E. J. Poynter, P.R.A. . 170

-

Portrait of the Right Hon. Stephen Lushington . âW. H. H.. . 171

(

The property of the National Portrait Gallery)

-

Portait of Keats . . . . . . . . â J. Severn. . 185

-

Portait of Trelawny . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186

-

Portait of George Meredith and his son Arthur . . . . . . 187

-

Portaits of the Prince and Princess of Wales . . . . . .188

-

âLondon Bridge on the Night of the Marriage of

the

Prince and Princess of Walesâ

. . . âW. H. H.. . 189

(

The property of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

-

Portait of Garibaldi . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190

-

Sketch âAfter the Ballâ . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 194

-

Portait of J. L. Tupper . . . . . 195

-

Portait of Fanny Holman-Hunt . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 197

-

Portait of Fanny Holman-Hunt . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 198

-

Festival of St. Swithin . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 199

(

The property of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

-

Sunset over the Valley of the Arno . . . . âW. H. H. . . 201

-

Isabella and the Pot of Basil . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 203

(

The property of the Mrs. Hall, Newcastle)

-

The Tuscan Straw-Plaiter . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 205

(

The property of the F. Austen, Esq.)

-

Design for Lectern . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 206

-

Bianca . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 207

(

The property of the Mrs. Mounsey Heygate)

-

Illustration to Child's Letter . . . . . . . . . . 208

-

âThe Birthdayâ . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 209

-

Ponte Vecchio, Florence . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 211

(

The property of the Victoria and Albert Museum)

-

The Senaculum . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 220

-

Jerusalem by Twilight . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 221

-

âAn Obstinate Muleâ . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 222

-

Tent at Bethlehem . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 223

-

Another of the Same . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 223

-

Portrait of the Crown Prince of Prussia . . âW. H. H. . . 224

-

View of Zion . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 226

-

A New Convert . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 227

-

Roof of my House . . . . . . . . By W. H. H. . . 227

-

The Guard . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 228

-

Taking Possession . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 228

-

Friends at Dinner . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 229

-

My Cook . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 232

-

Study for Fig Tree . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 229

-

Study for Head of Christ . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 233

-

Turning Night into Day . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 236

-

âDaddy at Bayâ . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 238

-

The Shadow of Death . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 242

(

The property of the Corporation of Manchester)

-

Queen Victoria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 245

-

The Beloved . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 246

(

The property of His Majesty the King)

-

Portrait of Cyril B. Holman-Hunt . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 247

-

Portrait of Charles A. Collins . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 250

(

The property of the Fine Arts Gallery, Birmingham)

-

The Terrace, Berne . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 251

-

Portrait of Edith Holman-Hunt . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 252

-

Portrait of Cyril B. Holman-Hunt . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 252

-

Sketch made in the Synagogue . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 253

-

The Triumph of the Innocents . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 254

(

The property of Mr. and Mrs. Sydney Morse)

-

Portrait of Kitchener . . . . . . . . . . . . .255

-

Sketch . . . . . . . . . . . .âW. H. H. . . 255

-

Another . . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 256

-

The Ship . . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 257

(

The property of the Tate Gallery of British Art)

-

âThe Painter's House,â Jerusalem . . . . âW. H. H. . . 259

-

Sketch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259

-

Study for St. Joseph . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 261

-

Portrait of My Baby Daughter Gladys . . . âW. H. H. . . 263

-

Two Portaits of my Daughter . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 264

-

Edith Holman-Hunt . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 265

-

Design for Portrait of my Wife and Daughter . âW. H. H. . . 266

-

The Father's Leave-Taking . . . . . .âW. H. H. . . 266

-

âCome, Buy of Meâ . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 267

-

âOne Touch of Natureâ . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 268

-

Portrait Designs from my Daughter . . . . âW. H. H. . . 269

-

Edith Holman-Hunt and her Son . . . . âW. H. H. . . 270

-

Amaryllis . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 271

(

The property of Mrs. George Lillie Craik)

-

Portrait of Cyril B. Holman-Hunt . . . . âW. H. H. . . 272

-

Cheyne Walk, Chelsea . . . . . . . By H. and W. Greaves 273

-

Portrait of Gladys Holman-Hunt . . . . . By W. H. H. . . 274

-

Portrait of Hilary Holman-Hunt . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 274

-

Another of the Same . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 275

-

Portrait of Gladys Holman-Hunt . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 275

-

Portrait Design . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 275

-

Miss Flamborough . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 277

-

Portrait of W. Holman-Hunt . . . . . . . . . . . 279

-

Six Picture of Draycott Lodge, Fulham . . . . . . . 280-282

-

The Triumph of the Innocents . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 283

(

The property of J. T. Middlemore, Esq., M.P.)

-

Design for Family Group . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

-

âDr. Johnson in the Market-Placeâ . . . . âM. J. Lawless . 286

-

Christ among the Doctors . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 289

(

The property of J. T. Middlemore, Esq., M.P.)

-

The Bride of Bethlehem . . . . . . . By W. H. H. . . 299

(

The property of Mr. Henry Haslam)

-

Sorrow . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 301

(

The property of Mrs. George Lillie Craik)

-

Portrait of D. G. Rossetti . . . . . . . . . . . 302

-

âMaster Hilary,â the Tracer . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 303

(

The property of H. L. Holman-Hunt, Esq.)

-

The Moat, Fulham Place . . . . . . . . . . . . 304

-

Bas Relief . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 308

-

Examples of Fractured Glass . . . . By Professor Vernon Boys 309

-

Design for Sir Galahad . . . . . . . By W. H. H. . . 309

-

Miss Stella Duckworth . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 310

-

Miss Eugenie Sellers . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 310

-

Hilary L. Holman-Hunt . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 311

-

âThe Lady of Shalottâ . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 312

-

May Morning on Magdalen Tower, Oxford . . . âW. H. H. . . 313

-

The Square, Athens . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 314

-

Corfu . . . . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 315

-

The Nile Postman . . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 316

-

The Miracle of the Holy Fire . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 317

-

âOld Buried Goldâ . . . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 318

-

Study for Vision of the Shepherds . . . . âW. H. H. . . 319

(

The property of H. L. Holman-Hunt, Esq.)

-

Portrait of Holman-Hunt . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 320

-

The Importune Neighbour . . . . . . âW. H. H. . . 321

(

The property of Fine Art Gallery, Melbourne)

-

G. F. Watts in his Garden . . . . . . . . . . . 324

-

Portrait of Holman-Hunt . . . By Sir W. B. Richmond, K.C.B. 325

-

Another of the Same . . . . . . . . . . . . . 328

-

The âPearlâ . . . . . . . . . . By W. H. H. . . 333

(

The property of I. Gollanez, Litt. D.)

-

âFoundâ . . . . . . . . . . . By D. G. Rossetti . 348

-

Sonning Acre . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 380

-

Another of the Same . . . . . . . . . . . 381

-

Portrait of W. Holman-Hunt and Professor Flinders Petrie . . . . 382

-

Ancient Dovecot . . . . . . . . . . . . . 383

-

The Hand of Holman-Hunt . . . . . . . . . . . 383

-

The Stone in the Crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral . . . . . . 384

Â

Note:

This page is one quarter the size of the other pages in the book.

ERRATA

Vol. II.

- p. 89, line 18, âListerâ

should read

âLeslie.â

- p. 155, lines 5, 10; p. 399. lines 4, 7, 22, 28; p. 400, lines 7, 19,

âSèvreâ

should read

âSèvres.â

- p. 342, lines 42, 46, 50, âG. F. Stephensâ

should

read

âF. G. Stephens.â

- p. 343, line 2, âM. Madox Brownâ

should read

âF. Madox Brown.â

line 31, âF. J.

Stephensâ

should read âF. G.

Stephens.â

Â

But whosoever chooseth the life to come and directeth his endeavour towards the same,

being also a true believer, the endeavour of these shall be acceptable unto God.

â

Al Koran.

The winter came with its succession of storms of some

daysâ duration, leaving two or three feet of snow on the ground.

My first hope had been to complete my picture of âThe

Scapegoatâ in time to send it to London for the Royal Academy, but owing to the

delay in finding the third suitable goat, this had become impossible and the work was

still incomplete at Easter when many English visitors arrived.

While the city was more cheerful than usual, Lord Napier and Ettrick, with Lady

Napier and her young sons, arrived, and Frederic Lockwood, whom I had known at Cairo, came

over to meet his sister.

I delayed showing them the âAzazelâ until it should be nearer

completion, and when I had that pleasure, their discriminating and cultivated judgment was

of the greater service to me, since I had been for so long removed from the opportunity of

hearing artistic opinion.

1

Transcribed Footnote (page [1]):

1While preparing a second edition I have come upon a letter of

interest at this time from D. G. Rossetti, even more important than it seemed to be when

it was received by me. I regret that the closing lines are missing; I give it not only

for its contemporary news, but also for its bearing upon Gabriel's picture of

âFoundâ and my picture of

âThe Awakened

Conscienceâ

âW. H. H.

30

th January, 1855.

Dear Hunt,â

I am quite ashamed in setting-to at this letter after so long a promise-breaking

silence; but as I should be still more ashamed at seeing you again, and remembering

your friendly letters, as the only ones which had passed between us, I bespeak a

little very comparative content with myself by writing even thus late. I am

beginning this at Albany Street where Christina, seeing the paper lying on the table

and hearing of its destined use, has just charged me with a charge to you to bring

home an alligator (an allegory on canvas not to be accounted a fair substitute), in

which she proposes that a few of your select friends should be allowed to take

shares, after which its sudden presentation to the Zoological Society should make

the fortunate Joint Stock Company members for life of that dismayed Institution.

This, she thinks, is a project of moderate promise and a great additional incentive

to defer writing no longer.

One great reason for my not writing long before this has been the wish to have

something worth saying to you of my own doings and plans, and this no doubt you have

guessed. It is possible that Sisyphus, for the first few rolls of his stone, may

have dwelt on the causes

An ancient quarry which penetrated under the city had been recently discovered. The

Mahomedans were very jealous about it, and forbade

Transcribed Footnote (page 2):

of his failure at some length and vowed to do the trick yet; but one inclines to

believe that the occupation soon became and continues chiefly a silent one.

Anxieties and infelicities, this sort among the restâdid not seem the

best subjects to write about; but they have not prevented my enjoying the tardy

justice done to you last year in your worksâthat is, in all quarters of

any consequence, and remembering how we were together while you strove bitterly

towards it, deserving it all the time in days that never come again.

I have no doubt that which you are doing now when seen, will bring to more than

completeness the result which was more than begun last time, and feel very

desirous to see your new works and have a first chance of learning what the East

is really like. I can tell you, on my own side, of only one picture fairly

begunâindeed, I may say, all things considered, rather advanced; but it

is only a small one. The subject had been sometime designed before you left

England and will be thought, by any one who sees it when (and if) finished, to

follow in the wake of your

âAwakened Conscience,â but not by

yourself, as you know I had long had in view subjects taking the same direction as

my present one. The picture represents a London street at dawn, with the lamps

still lighted along a bridge which forms the distant background. A drover has left

his cart standing in the middle of the road (in which,

i. e. the

cart, stands baa-ing a calf tied on its way to market), and has run a little way

after a girl who has passed him, wandering in the streets. He has just come up

with her and she, recognising him, has sunk under her shame upon her knees,

against the wall of a raised churchyard in the foreground, while he stands holding

her hands as he seized them, half in bewilderment and half guarding her from doing

herself a hurt. These are the chief things in the picture which is to be called

âFound,â and for which my sister Maria has found me a most

lovely motto from Jeremiah: âI remember Thee, the kindness of thy

youth, the love of thine espousals.â Is not this happily applicable?

âEspousal,â I feel confident from knowledge of the two words

in two or three languages would most probably be rightlier rendered

âbetrothal,â which is the word I want and shall substitute

as soon as I have consulted some one knowing Hebrew. The calf, a white one, will

be a beautiful and suggestive part of the thing, though I am far from having

painted him as well as I hoped to doâperhaps through my having

performed the feat, necessarily an open-air one, in the time just preceding

Christmas, and also through the great difficulty of the net drawn over him; the

motion constantly throwing one outâme especially, quite new as I was to

any animal painting. I wish that if anything suggests itself to you which you

think would advantage this subject, or any objection, you would let me know of it,

though otherwise than for such a purpose I cannot expect to hear from you before

doing this duty at least once again. I have not spoken of the subject at all to

any of our circle except Brown, at whose house at Finchley I stayed while painting

on it there, and Hughes, who happened to be painting at my rooms when I began it.

Since Christmas I have been prevented from working on this picture by illness

first, and since by having other things necessary to be done, but I hope soon to

be on it again, though even were it ready in time I should have small thoughts, as

yet, of sending it to any exhibition unless compelled. It was originally a

commission from that fellow X., a subject which he chose himself from two or three

I proposed to him; but he either is or professes himself too nearly ruined now to

buy more pictures, so I suppose that chance is up. But it is no use writing about

bothers of that kind.

The other day I had a visit from Moxon (at Millaisâ kind suggestion I

believe), asking me to do some of the woodcuts for the new Tennyson, on which I

hear you are at work already. I can find few direct subjects left in the marked

copy he has left me, and shall probably do âVision of Sin,â

âPalace of Art,â and things of that sort, if I get into the

way of liking the task well enough to do them well; but I think illustrated

editions of poets, however good (and this will be far from uniformly so), quite

hateful things, and do not feel easy as an aider or abettor. I have just done one

for Allingham's forthcoming volume, and know that were I a possessor of the book I

should tear out the illustrations the first thing.

By the bye I have long had an idea for illustrating the last verse of

âLady of Shalott,â which I see marked to you. Is that a part

you mean to do, and if not and you have

only one design in

prospect to the poem, could I do another? One of my occupations at present is a

class on Monday evenings at the âCollege for Working Men,â

got up by Maurice and others in Red Lion Square. Ruskin kindly came forward to

teach drawing, but as his class only comprises foliage, etc., I have added a class

for drawing the figure and have begun by setting the pupilsâmostly real

working-men carpenters, etc.âto draw heads from Nature, one of them

sitting to the rest. Even already there are one or two of them doing really well.

I draw there myself, and find that by far the most valuable part of my

teachingânot only to me, but for them. I have (of course) one or two

subjects which I hope to get immediately in hand as pictures. I have always feared

to attempt a figure of Our Saviour, but if opportunity serves, hope to paint this

year one which I have long wished, on the motto âWhose fan is in His

hand.â

entrance, but Cayley, the eccentric traveller, and some young

Englishmen were anxious to see it, and Sim and I undertook to conduct them. In the

afternoon we left the city by separate gates, and waited at a distance until the last

belated wayfarers had re-entered the walls, and the guards had shut the heavy doors upon

themselves. The country around was by that time quite abandoned, and we made the necessary

circuit to the Damascus gate, cautiously creeping close up to the foundations, beyond

sight of the city ramparts, in order to reach the opening to the cave. It was not

difficult to remove a stone or two put there to seal up the entrance, and one by one we

crept in. After about eight feet of level rock there was a drop of the same extent; inside

we lit our candles and waited for the whole party to descend. We proceeded, touching the

quarried rock with our hands; following along we came to chambers where the quality of the

stone had tempted the ancient masons to extend their operations. In parts water dripped

from the roof into pools, where the splashed surface of the rock was glazed and rounded;

the blocks lying about had all been worked into measure and form, as the Bible describes

the stones of the Temple to have been. Some of these had been discarded and left on the

ground, presumably because of a discovered flaw. While most of us were examining a large

door nearly finished, which was fresh as if of recent work, we were dismayed by the loud

explosion of some firearm in our rear, the noise of which reverberated alarmingly through

all the hollows of the cavern. It turned out that a pistol had been fired with extreme

thoughtlessness by one of our company, âmerely for fun.â How far it

could be heard by the inmates of houses above our heads we never knew, but although we

could

Transcribed Footnote (page 3):

This letter is unbearably egotistical hitherto. Let me try if I have any news of

friends, but I see few, and those seldom. Woolner seems, after all, to be

disappointed of that commission, as perhaps you have heard from him. It is a

pleasure to have him again here, but I suppose it cannot be for long. He talks of

painting with me, so as to be able to portraitise on his return to Australia, both

in paint and clay, and so be able to accept a larger number of commissions. This

would, I should think, be a wise thing, and I have no doubt he would at once be

perfectly successful in painting when he only began rightly. Brown has just added

a little boy to his family; but I fear what would and ought to be a cause of

congratulation, is only one of anxiety just now.

He is painting again on that picture of âEmigrants,â which

is now far advanced, but fortune does not seem to turn yet. You heard perhaps of

one result of his discouraged state some time backâhis sending two

picturesââKing Lear,â and a large landscape just

then finished after many monthsâ work, to a wretched Jew shop-sale,

where they fetched nearly the price of their frames. Of course, this injured him

in more than one way. You are almost sure to have heard of X's attempt months ago

to put up your âTwo Gentlemen of Verona,â and a few more of

his pictures to sale at Christie's when yours reached in real biddings

£300, was run up ostensibly much beyond that by his

touters in the room, but finally remained with him, not reaching though apparently

approaching if I remember, his reserved price of

£500, which was the one he put on it by my advice. I do not know

whether he has since sold the picture, but at that time it returned with him to

Ireland. Among deaths, you have perhaps heard that of another of our early

âpatrons,â Cottingham, who was one of the passengers lost in

the

Arctic last September; and of the end of poor North, at New

York, by a quarter of an ounce of prussic-acid, of which there was a long account

in the

Daily Newsâyou may see it one day, as Woolner

has it. It is a subject one cannot talk of, and too hopelessly sad even to dwell

much on the mind, however sincerely one regrets and pities him.

Brown talks of obtaining a country mastership in the School of Design, and I

believe has lately taken some steps towards it.

D. G. Rosetti

believe that they would be more afraid than ourselves, we became

anxious lest our place of exit should be obstructed. When the quarry had been first

entered, on its discovery by a shepherd, the skeleton of some unfortunate explorer had

been found, who had evidently sought a means of escape in vain.

The Pashas of Jerusalem appointed from Stamboul were changed very frequently in

these days; one came preceded by a reputation for superiority to fanatical prejudices, he

arrived not only without a bevy of many wives, but without a single one. He was known as

âKiamil Pashaâ; he was, I believe, the same who at the installation

of the Young Turkish party became their new Grand Vizier. Stories were told of

Â

Â

KIAMIL PASHA WAS RE-APPOINTED GRAND VIZIER IN 1912

him as of a Turk of rare enlightenment. He conceived a cordial friendship with

Dr. Rosen, the Prussian Consul, and visited him as an intimate so habitually that ceremony

was dispensed with, and Madam Rosen (daughter of Moschelles, the musical composer) went

about her household duties superintending the servants without consideration that her

methods were being studied. The Pasha soon avowed to the Consul that the European system

of managing a house was distinctly to be preferred to that of the Oriental, in that

dishonesty in the servants was effectually checked; this he declared was truly excellent,

but still he added there is one point I cannot understand: your wife guards you from

dishonest servants, but what check have you to prevent her from defrauding you herself?

Sir Moses Montefiore came early in the spring on a charitable mission.

While he was encamped outside the Jaffa Gate I wrote to him

concerning the misinterpretation of my innocent object as a painter, by the Jews and their

rabbis, and I begged that he would explain my purpose, and induce the rabbis to remove the

interdict which prevented the more orderly minded Jews from coming to me. Mr. Sebag

Montefiore saw me on the subject, and promised attention to the question. Mr. Frederic D.

Mocatta arriving rather later, I urged the point with him also; his knowledge of art and

artists enabled him to understand my difficulties the better, so now I had improved

prospect for âThe Templeâ picture, when I could be free again to

work on it.

It had been a vexation to me during its progress to have no opportunity of seeing,

from the platform of Moriah, the distant slope of the northern Olivet which came into the

background of the picture. Since the crusading successors of Godfrey de Bouillon were

chased from Jerusalem no Christian, but in disguise or by stratagem, at a risk of very

probable death, had entered its precincts.

I had been able only to satisfy my interest in the sanctuary by such view as could

be had from the roofs of houses on a height.

Early in April, however, the Duke of Brabant, the heir-apparent of Belgium,

arrived in Jerusalem, and it was whispered that the very enlightened and francophile Pasha

of the day was making great efforts to gratify the Duke's ambitions to enter the

enclosure. The Prince had been provided with a firman to enter the Mosque area, yet it was

probable, as with many previous travellers coming from Constantinople, that His Highness

would be told it would be fatal to the lives of all who attempted to act on the Sultan's

favour; but gossip had not much to indulge in, and soon it was said that the Duke would be

privileged to enter the Hareem. I called on the Consul, and urged that if it were so, the

English residents might also pass the sacred gates. He told me that this was generally

felt, and that he was watching to secure the opportunity. On the Saturday of the Greek

Easter, he sent me word to hold myself in readiness that afternoon. Earlier in the day I

had witnessed the ceremony of the Miracle of the Sacred Fire in the Church of the

Sepulchre.

This year no Russian pilgrims were present, yet the building was crowded with

strangers, male and female, from Greece, Armenia, Egypt, and Abyssinia; in fact, in this

respect the occasion was like the ancient Feast of Pentecost, bringing strangers from all

parts, and such resemblance was undoubtedly in mind when the original form of this

ceremony was instituted, for it is on record that an artificial dove descended through the

opening of the dome, carrying the fire with it into the sepulchral shrine. Curzon in his

Monasteries of the Levant describes his experiences in 1834, when

three hundred people were killed in the disorderly crush. Kinglake, who was there the next

year, treats of it in his most graphic manner, and Dean Stanley was a witness of the scene

in 1854, a year before my own visit.

At 4 P.M. I presented myself at the appointed place of entrance to the Mosque, and

found the secretary nearly alone. The company increased by ones and twos, and the Pasha

had just counted twenty-one when our Consul arrived with a train of some thirty English

subjects, clergy with their wives, and other ladies connected with mission work. Very

obvious was the bewilderment of the Pasha, but his politeness was equal to the need. When

he left the apartment time after time, and returned with no show of having advanced

matters, I was inclined to suspect that he had as poor an estimate as I had of the

interest which the majority of the crowd were likely to take in the features of the

Mosque, that he would therefore consider that the risk should not be incurred, and that it

might be wise to delay action until advancing darkness should render our entrance into the

sacred place impossible.

During this time it transpired that the Pasha was intent upon the success of a

summons issued to all the dervishes of the Mosque to assemble in a chamber of the Hareem

to discuss a point of great moment, which had to be considered by the holiest authorities.

Concluding it was the question of admitting the Belgian prince which had to be debated,

they thronged into the building to utter their loudest protests. Delays arose in making

certain that all the dervishes were assembled, and then the doors were locked, and a

company of soldiers posted outside for an hour to turn the council-chamber into a prison.

After this precaution, the Duke of Brabant and his suite advanced, and we were

bidden to follow; passing a few courts belonging to the house, we emerged from a dark

passage into the great area which includes the site of the ancient Temple.

It was a moment in life to make one's heart stir as the door was turned on its

hinges, and the way into this long-dreamed-of, much-longed-for, yet ever-forbidden sanctum

was at last open to us.

On my first arrival in Jerusalem, wandering alone, I had entered the gates by

mistake, but before I had realised my position I was set upon by one, then by two blacks,

and threatened by an approaching crowd of wild and dark Indians and Africans, from whom I

escaped by a hasty retreat. Now the place was empty, and I gazed with boundless delight on

the beautiful combination of marble architecture, mellowed by the sun of ages, of

mossy-like cypresses, and Persian slabs of jewel hues; but at once I was told that no one

must linger. At the foot of the steps we were ordered to take off our boots; wearing

Turkish shoes, I had no difficulty, but many were unprepared; and it was one of the grim

mockeries of fate that at such a moment ladies and gentlemen should intensify the

hideousness of modern costume by hobbling about in lacerated stockings, carrying

Wellington boots and fashionable shoes in their hands. Unfortunately the Royal Duke gave

no sign of caring for the wonders about him; he sometimes glanced to right or left as the

guide referred to different objects, but never once did he pause from his swift march

around the Mosque As Sakreh or through Al Aksa to

dwell on any object, nor did he turn aside to examine anything

out of the direct line of the prescribed route; an Arab in Westminster Abbey would not

have been more supremely superior. When Sim and I ran off to look at the interior of the

Beautiful Gate, we were quickly summoned back by a messenger, with a caution that it would

be imprudent to go alone, in the face of possible danger from concealed dervishes. We

pleaded that we were armed, and would take the chance, but the Pasha still objected, and

we had to abandon our hope. I left with my curiosity only increased. On emerging from the

gate to

Via Dolorosa we saw a body of Moslems in the street, who glared

with hatred such as only religious rancour can inspire, but they allowed us to disperse in

peace.

Montefiore, before the close of his charitable work, sought and obtained

admittance to the Mosque. His entrance was not so shocking to the sons of Ishmael as to

his own brethren. The Rabbis pronounced against the part which he had taken in availing

himself of such opportunity, as the exact spot of the Holy of Holies not being known, he

might have offended in treading on the ground sacred for the High Priest alone.

If all the Christian visitors to the Mosque that day felt the respect for

Mahomedans which the sight of their reverent conservation of the sacred spot awakened in

me, and if the sons of Hagar assembled at its doors had thus been able to read our

feelings, their attitude towards us could scarcely have been other than that of brotherly

pride in such hospitality as all followers of the Prophet are enjoined to exercise. From

the day that Abraham met Melchisedek, this site has been the theatre of events which have

struck deepest roots in the life of humanity. It has been the sanctuary of Jew, Christian,

and Moslem. Had the Jews still possessed it, there would have been signs of bloody

sacrifice. Had any sect of Christians possessed it, the place would have been desecrated

either by tinselled dolls and tawdry pictures, as is the case in the Church of the

Sepulchre, or else by the ugliness, emptiness, and class vulgarity of the Anglican and

Prussian worship, as found in the city of Jerusalem. In the case of the Moslem there was

not an unsightly nor a shocking object in the whole area, it was guarded, fearingly and

lovingly, and it seemed a temple so purified from the pollution of perversity that

involuntarily the text, âHere will I take my rest for ever,â rang in

my ears. The past, so many pasts, stood about, even the very immediate present was a

mystery and a wonder; it was an epoch of the world's history, a summons to reflection, the

moving of the index finger. The Osmanli sands were running fast, and the hour-glass might

soon be turned; but I felt that Hagar's sons had been appointed to the great purpose,

keeping the spot sacred until the sons of Sarah should be enough purified by

long-suffering, to take it again into their charge.

I had not attained my object, not having been able to make even the slightest

scribble of the landscape for my picture. I had, however, gained the distinct knowledge

that the only point from which it could be obtained was the roof of the âMosque

of the Rock.â That I should

ever be able to mount upon this, unless it might be in the guise

of a workman, seemed quite out of hope, because only Moslems were employed in the

reparation of the roof.

Photographs and exhaustive discussions have now made familiar the variations in

the character of the outside and the inside of the Mosque As Sakreh. Remarking upon the

evidence pointing to its having once been a Christian church, which its interior suggested

to me, my companion said, âI see you are a convert to Fergusson's

theory.â I had not then heard of the architectural critic's conclusions, drawn

from examination of drawings made under extraordinary circumstances by Catherwood and

Bonomi.

In May all the pleasant English company went away together, for the Consul had the

opportunity of visiting Gerash, which was not always open to travellers, and the chance

was eagerly seized by those who made that place a fresh stage on their journey. The

temptation was great for me to join them, but the time for my work was too precious to

spare, and a discovery I had made did much to decide the question for me. The gun which I

had carried on my saddle, and which had often served me in good stead, had a crack in the

stock; it was not yet in danger of causing disruption, but when it was fired the strain

dipped the barrel enough to make it hit low. A much more serious and troubling discovery

was, that the revolver, on the efficacy of which my life had more than once depended, had

reverted to its old fault of getting fixed in the lock; I therefore called my landlord and

said: âI want you to go to âFredericâ and deliver my

pistol; explain to him yourself that it is loaded and cannot be fired off because of the

defect for which I first sent it to him; he returned it repaired, but it is still

untrustworthy, he must now put it into proper working condition at any cost, for a pistol

that cannot be trusted is worse than useless. Say that I know he is clever, and quite

capable of curing the fault.â

My landlord was a philosopher who at all times strove to enforce consideration for

the weaknesses of others. âVell, vell, yas! ve most âave patience.

Frederic, poor fellaw! he unhappy. I go to Frederic, I say, âVy for you not

marry, plenty nice gals âere now, you are von ov us, you av goot busness, vy not take

vife?â Votââ and here he shrugged his shoulders

commiseratinglyââ âe say, âI stay âere only to die like my

vrent die, an' den wot my vife do?â He tocht in âed, poor fellaw!â

âI know, I know, Max, but mind you give him my message, and take care that no

one touches the pistol but yourself, till you deliver it into his hands with the caution

that it is loaded,â said I.

The next morning Max, who was as conscientious as he was proud of his proficiency

in English, assured me he had acquitted himself of his commission scrupulously. He said

Frederic had listened attentively, and pleaded that the pistol needed a new spring. He was

too busy for a day or two to attend to it, however, and would not take it in hand until he

could finish it properly.

âAh,â said Max, âhe quite mad, poor fellaw! âe

âang id op, bak shobâ; by which I understood that he had put it safely by for

the present.

On a previous Sunday there had been an overflow of water at Beir Yoab, and the

people of Jerusalem had gone out to see it, some with keen enthusiasm because it seemed

like the return of the promised

early rain, which they said had been

withheld since the destruction of the Temple. I walked with Dr. Sim in the midst of the

throng, and we met Frederic all alone at St. Stephen's Gate; he smiled pleasantly but

sadly to our salutation. We knew no German and he knew no English, so we exchanged a few

words in Arabic and separated.

The evening after my message to Frederic, I called on Sim to choose the wild

goat's skull for my âScapegoatâ picture; he had a large collection

of such things. He told me that he had just come back from seeing poor Frederic, who had

been shot by his apprentice in his own shop! He had extracted the bullet, and hoped from

its small size that it had not pierced the body, but travelled round as bullets partly

spent occasionally do. It was desirable to leave the patient undisturbed, he said.

Frederic, it seemed, had been working at an anvil in the front of the shop, the apprentice

came in, while the master, who was steadily filing, became apprehensive that the fool was

at some mischief, and turning quickly, said, âYou are not touching that loaded

pistol?â The boy in his fright nervously pulled the trigger, and the bullet

struck the master in the side. He fell on the floor, the noise attracted a crowd, who came

in and surrounded him. He groaned, âAh, I am paid now. I knew it would come to

this.â Waving the people aside, he said, âI am going away to

die,â and jumped up to run through the street up a steep lane into the door of

the German Hospice, where he threw himself on to a bed, and there the doctor had seen him.

From Sim's favourable opinion I encouraged the idea that the man was not wounded

to death; but on the morrowâfourteen months after the death of his

friendâthe lot had fallen upon him also.

It was my accursed revolver that had brought about this dire tragedy. I tell such

stories not in support of any theory, but because they claim record as strange personal

experience. There are people in Jerusalem now who remember Frederic with sorrow, and who

wonder what became of the loved maiden in Germany who was to have been his wife.

Although the Exhibition date was past, I was working hard to finish

âThe Scapegoatâ and send it away to Mr. Combe. I trusted that

possibly among the patrons of art who had expressed a wish to have some picture of mine

one might be found to purchase it, and so make me more at ease and free to prolong my

stay; in any case, it would relieve the dejection I often felt at having brought none of

my works to completion. My time was, however, seriously taxed in consequence of a

contention I was drawn into with the bishop about the character of one of the Arab

converts. I will say no more on this

subject, but should any wish to know of the business, they may

learn all particulars from a pamphlet which I published after my return to England. Yet,

lest the story should be taken as a proof that I look with a feeling of disrespect upon

English Missions, let me say that the circumstances were exceptional.

Early in the summer of this year two regiments of soldiers were sent up to quell

disturbances caused by the fellahin. It was not alone the outbreak against the government

near Hebron, of which, at the request of the Consul, I had made a report, but in the

western hills in the neighbourhood of Betir the sheiks were fighting for the mere pleasure

of fighting and delight in bloodshed, and one indeed deservedly acquired for his cruelty

the name of âbutcher.â The newly arrived soldiers were encamped upon

the slopes of the Pool of Gihon, and thus it seemed as though indirect pressure alone was

to be used against the fellahin; travellers were, under this military influence, enabled

to use the roads in greater safety; perhaps it was this that brought the Prussian

Quarantine doctor from Hebron to Jerusalem. Seeing him riding with the Prussian Consul as

I was going out of the Jaffa Gate to enjoy the evening air after a fatiguing day's

painting, it seemed to me that he had not seen me, so I deferred accosting him. It was a

mistake which I often regretted later, for on the morrow he had returned home, and in a

few weeks he committed suicide.

The soldiers after a month's encampment moved for a few weeks to the Pools of

Solomon; and, when the fellahin were quite off their guard one night, they surprised the

insurgent villages about Hebron, slaughtering and burning to the content of the Ottoman

heart.

I had no contribution at the Academy Exhibition, and I had told my English

correspondents that I might suddenly give up further attempts in Syria and return, but I

had a great desire to know of the treatment of our School this year, thinking that the

election of Millais might be a mark of more favourable feeling. A letter from him

enlightened me painfully on this point; a few extracts will explain the disillusion; it

also gives some reference to his approaching marriageâ

Langham Chambers, Langham Place,

London,

May 22, 1855.

My dear old friend,

All the hurry and excitement of the R.A. is over, and yet I find myself delaying

until it is absolutely necessary that I should tell you first that next month, please

God, I shall be a

married man. What think you of this? You must have

partly expected this, and will not be knocked down by this sudden announcement. I have

let the time slip by me so fast that I am at a loss what to tell you first....I have

gone so far as to take a place near her family at Perth for the autumn, and I leave this

in a fortnight's time, when to return I donât know....Lear has been here just

this moment telling me of your letter he has received. Collins also received one. When

you come back, you must come and see me. I am afraid I shall not be in London to receive

you when you arrive....

Apropos of work, my picture (âThe

Firemanâ) this year has been blackguarded more than ever;

altogether the cabal is stronger than ever against every good

thingâsuch injustice and felonious abomination has never been known before.

Fancy Aââ, Bââ, and old Satyr

Cââ as hangers. Collins above the line is the Octagon, Martineau

at the top of the Architectural...my picture against the door of the middle room. The

very mentioning of these disgraceful facts incenses me so that I begin to tremble. I

almost dropped down in a fit from rage in a row I had with the three hangers, in which I

forgot all restraint and shook my fist in their faces, calling them every conceivable

name of abuse. It is too long a story to relate now, but they wanted to lift my picture

up, after I had got permission to have it lowered three inches, and tilted forward so

that it might be seen, which was hardly the case as it was first hung. Oh! they are

felonsâno better than many a tethered convictâso let them pass.

The Exhibition you will see, so there is no need of any mention of it. William I never

see scarcely, as he lives down at Kingston. I am going to be married so quietly that

none of my family come to the wedding. Good gracious, fancy me married, my old boy!...It

is quite impossible to foresee the end of anything we undertake. Every day I see greater

reason to be tolerant in judging others. We cannot reckon upon ourselves for the safe

guidance of a single project. But I must not fill this letter with truisms....If I omit

to tell you anything of interest you may afterwards find out, it will be from

forgetfulness....Wilkie Collins is here and sends greeting. To-morrow is the Derby Day.

Last Epsom I went too, we went together with Mikeâyou remember....My dear old

friend, I feel the want of you more than ever, and art wants you home; it is impossible

to fight single-handed, and the R.A. is too great a consideration to lose sight of, with

all its position, and the public wealth and ability to help good art. When Lady Chantrey

dies, the Academy will have funds at its disposal for the purchase

yearly of the best living works, and all this should be in

our

hands. In my contest with the hangers I said I would give up my associateship if they

dared to move my picture, which so frightened them, I suppose, that they

didnât touch it afterwards.

I want you back again to talk

over this matter of Exhibition. I am almost indifferent about these things now, and yet

I think it a duty, for other poor fellows like Brown (whose three pictures were

rejected), Anthony, Seddon

were turned out also.

Ever affectionately yours,

John Everett Millais.

Miss Mary Rogers had come to Jerusalem with her brother, the future Consul of

Damascus, and she gave me the London art news. One most important item was the appearance

of a new artist, with a large picture representing the procession of Cimabue's picture

through the streets of Florence. The artistsâ name was Leighton, and the work

was strikingly admirable, independent of the fact that it was his first exhibited original

composition; his father had allowed him to paint it on condition that if not successful he

should finally relinquish art. This picture was in great favour with artists, and the

Queen secured the young painter's future success by buying it for £500.

While I was completing âThe Scapegoat,â for the first time

in the history of Turkish rule cannons were fired for a Christian monarch, on the 24th of

May, Queen Victoria's birthday. The European ladies, hearing that my picture would soon be

sent to England, now came in little groups to see it, one of these expressed a strong wish

that some

sound and practical landscape painter could come and help me

with wise counsel as to the finishing of it. Afterwards I heard that her commiseration had

been stimulated by the perusal of an article in a London paper brought to her by a

neighbour, wherein I was held up as a proverb of artistic extravagance. On 15th June the

work was finished, and put into its case. I rose early, and Sim, Graham, and I sallied out

of the Jaffa Gate at 4.30 A.M. Sim, was leaving and going as army

surgeon to the Crimea. He had made himself deeply loved and valued, and many of the

grateful people accompanied us a mile or two on the road to take leave of him. I went to

Jaffa with paint-box packed up, so that if I saw need, I might put further finishing

touches on the picture before shipping it. The ride was delightful. Graham lent me his

clever

rhowam-paced pony, and Sim had an Arab which he was taking with

him by sea, and as the third of our party was well mounted, we careered across the

cornfields, many of which were cut, while others were being reaped. The trusty Issa

meanwhile could be left with the baggage. It was high time I had such change, for I was

far from well. The rest of two hours at the Ramla Convent with the cheery old monks

delighted our hearts, and we arrived at Jaffa in the afternoon, when all seemed careless

peace with the retiring sun, and as I passed my picture through the customs and took it on

board, I felt cut off from the cause of many galling anxieties, and trusted issues to

gentle Providence.

I had intended to stay with Graham a few days at the seaport, but the next

afternoon Issa, his servant, who was deeply concerned in the proceedings conducted by the

bishop to which I have lately referred, came to me with news gained from later arrivals

that caused him deep concern, and I offered to ride back to Jerusalem with him in the

night, which he eagerly accepted. On my return I sat down before my

âTempleâ picture to take stock of its condition and of my prospects,

improved by the intermediation of my friendly Hebrew advocates, Sir Moses Montefiore and

F. D. Mocatta, and at once took steps to recommence work.

Graham soon returned from Jaffa with health restored, and I frequently accepted

his invitation in the hot summer to sleep in the refreshing air on Olivet. The window of

this tower overlooked the Valley of Jehoshaphat, Gethsemane, and all the slopes of the

city, and a good telescope was mounted on the sill. On moonlight nights, while my friend

read aloud a king of literature for which I cared little, I could sit at the open window

resting my brow against its cool lintel, and turn my eyes upon the traces left by the

successive masters of the city since the days of Solomon, and upon the land so little

changed since its history was first written upon it.

No scene could offer more for reflection. Many elements were wanting to satisfy

the fullest sense of beauty, yet there was a solemn loveliness of expression settled in

all the region, with centres of mystic suggestion that enchanted my eye, while my mind was

enthralled by the thought

that this spot had been the place from which in turn the leading

nations of the world had been addressed as from heaven itself. Walls, towers, domes,

minarets, and vacant spaces in succession made my regard wander across the wide prospect,

and in and out of its intricate features. Lying there under full moonlight, the calm

picture appeared as formed in mother-of-pearl, with rare points glinting among the

opalescent hues. There were no street lamps in any part of the town; all bazaars were

closed, most good men were in their homes, open casements revealed inner lights with

families sitting at their last meal of the day; and elsewhere through perforated walls

could be traced small companies on the roofs enjoying the cool night. Towering above the

houses were the crowns of palm trees distributed among the courtyards inside their

protecting walls. Afar, high up, nearly screened by buildings, were the Armenian gardens

occupying the locality of Herod's Park and of the house of the High Priest, and there

still slept a group of huge fir trees, one of which spread its sheltering branches around

a delicate arboreal spire of cypress. Groves of olives were on southern Zion, and to the

north of the walls was another plantation, amidst which was a massive sycamore near to a

tower of necromantic tradition. The sombre trees mapped out the blanched limestone

buildings and surfaces into intelligible shapes and helped to frame the ancient ramparts.

The cupola of the Church of the Sepulchre with the adjoining tower stood in the heart of

the city; wild growths spread over deserted spots, the remains of fallen buildings whose

foundations were buried in their own ruins. The south-eastern corner of the square of the

city was the Temple enclosure, whose history we know more continuously than that of any

place on earth. Marble, alabaster, Persian tiles, and forms of early Byzantine design were

beautified by the contrast of vegetation, deep and rich, fed by the hidden waters at their

roots. Then the stately cypresses whispered together. The structures known as

âThe Dome of the Rockâ and Al Aska divided the mind as to the site

of the Holy of Holies, for the dimensions of the ancient Temple area were not enough to

include both buildings; as though patiently sleeping, they rested like palled shapes in a

heavy dream, detached by moonlight and moonshade. Although the platform was an open stage

from which the actors had departed, yet fancy would people it with their spirits, prophets

and martyrs stood arraigned there, delivering direful warnings from heaven. With tardy

repentance more pitiful, were those haunting the scene for mourned-over memories of crimes

towards the innocent; among them those who bewailed their bitterness towards the Son of

Love Himself, for Gabatha lay there.

Beyond this enclosure I was attracted by the moving lantern of a cautious

wayfarer; the flame taxed the sight as it hovered along, a very will-o'-the-wisp, through

antiquated arches, threading receding streets, being blotted out now for a few seconds,

now for a longer term, and anon as suddenly revealed. Occasionally home-seekers emerged

from

Â

Â

W. H. H.]

KUTEB MUEDDIN CALLING TO PRAYER

a door and stood still with a cluster of lights before taking

leave of one another, and then diverged and crept along different lines like the sparks on

unextinguished tinder, reminding me of what I had watched entranced in childhood and

called âQuakers going home from meetingâ; there was fascination in

the tracing of these wandering lanterns. One bewitching jewel of light attracted me as a

cherished possession, to be guarded with fear of its loss, as it came nearer and

disappeared within the belt of the hareem enclosure; but it was not long before it

re-appeared within the sacred square, where in passing it gilded marble pillars and

elaborated carvings, and flared upon capitals, architraves, and arches, until it halted at

the door of the minaret. In a few minutes appeared the flutter of the same light in the

gallery above, and when the lantern was put down, I knew another dear sign of life would

soon break out. The caller to prayer, with hands on the parapet, began his chant with a

voice like a resonant bell across the homes of hidden men who at the sound bent in prayer

and praise. The voice lingered and soared aloft; it was the chant of the âKuteb

Mueddin,â declaring itself emphatically in every fresh outburst, warbling,

carolling, and exclaiming with ecstasy, till it expressed the fulness of thanksgiving and

joy. It awakened the rapture with which I had heard the nightingale thrilling in his

listening copse, and the dreamy hope grew dearer, that the time was coming when there

could be no soul on earth not altogether at peace with the Father of Love. The singer

turned in his gallery to awaken sleepers in the south, the west, the north, and then again

in the full east. From a further tower a second psalmist responded, increasing his voice,

and there echoed around a refrain of melody, a strophe, and antistrophe, and as the chant

swelled a fuller height of rhapsody was attained; then by intervals the exalted strain

slowly descended into a tender chorus, and ceased when the very deadness vibrated,

consoling the yet unsatisfied and listening ear. Then all signs of restlessness took

flight, the lights in turn became extinct, and the whole mountain of men, women, and

children were at hush and rest, with nothing but the sound of barking dogs and screeches

of marauding beasts of prey to be heard.

Turning my attention from the window, I heard Graham's enthusiastic droning as

before, and when it ended my good friend asked if I had ever heard such an eloquent

sermon, and I felt able to say âNever!â

Â

Making the word of God of none effect through your tradition.

Falsehood is so vile that if it spoke of God it would take something from the grace of

His divinity, while truth is so excellent that when applied to the smallest things it

makes them noble.âRichter.

Returning to my âTemple,â the suppression

of the interdict of the Rabbis facilitated my appeals to the better class of Jews, and

though some of the men whom I now approached were of very humble means, they bore

themselves with unaffected dignity. One old fellow was heaven's own nobleman, he supported

himself by the profits of a little chandlery business; all day he squatted cross-legged on

his board in front of a cupboard with his wares: spices, coffee, sugar, arranged around

him within easy reach, he had numerous customers who purchased small supplies at a time.

On the Sabbath I always saw him at the Synagogue, and I learned that he was a Rabbi, who

by his independent industry the better represented the celebrated doctors of Hillel's

days. When I applied to him to sit, he explained that, having no relative or friend to

carry on the business if he were away the shop would have to be shut up, and that the loss

would be continued after he had reopened it, from the habit of his customers would

contract of dealing elsewhere; but my terms tempted him, the bargain was that he should

have four francs paid to him in the evening of each day, and that three more should be

written up to his account, to be paid when I had completed the work, and if he had been

punctual. He was always attentive and regular, keeping his part of the bargain, and never

doubted my good faith in keeping mine.

I am glad to record this case as one of many I have met with to the credit of the

Israelites. To prove the sincerity of some Jewish conversion to Christianity, and its

fitness for such men, a story known to me of actors still living in 1854 is sufficient. In

the year 1836 two Jews of unstable character had entered into partnership in a grocery

business. They purchased a small stock of coffee and stored it in their dark shop. They

indulged in stronger drink than that which their customers brewed, and in their cups they

quarrelled. The division of the joint property was a difficulty which no one of their