Rossetti Archive Textual Transcription

The full Rossetti Archive record for this transcribed document is available.

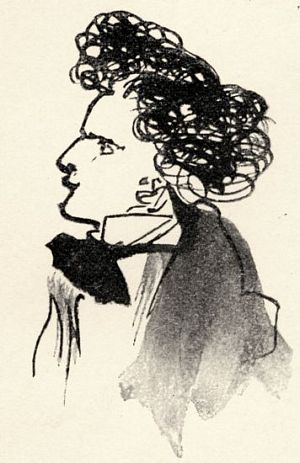

Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1862.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1862.

From a photograph by Messrs. W. & D. Downey.

brought out The Collected

Works of Dante Gabriel

Rossetti , both verse and prose,

original and translated. Into

those two volumes I put the

works which my brother had

published during his lifetime,

and also a moderate number

of other writings which he had

not published, but which I

esteemed suitable for appear–

ing in such a form. Some

other things of his, remaining

in my possession, were ad–

visedly excluded.

opinion exists on questions of

this kind, it may be as well

to explain my position in the

matter.

is as follows: If a writer has

attained a certain standard of

merit and reputation—and I

hold that my brother had

attained that standard—all that

he wrote, good, bad, and in–

different, should sooner or later

be published; omitting only

such productions as from

their subject or treatment (apart from the direct question of literary merits or

demerits) may be unsuited for the public eye. The good things should be

Copyright 1898, by W. M. Rossetti.

interesting or curious as coming from an eminent man. They are documents

subserving the man's biography, and may from that point of view be as important

to reflect upon as even his best performances. A sensible editor would of

course give some adequate intimation as to what he considers indifferent or bad,

so as to safeguard from misconstruction both his author and himself. In the case

of Shelley, for instance, it appears to me that, in a complete or scholarly edition,

the public ought to be made aware that the poet who eventually wrote Prometheus

Unbound and The Witch of Atlas did also at an earlier date indite such unmitigated

drivel as the verses in St. Irvyne , and was at that date, though no longer a child,

incapable of writing anything better. This latter literary and biographic fact is

only a shade less worthy of note than the former, and from the former its

importance is derived.

myself: in the case of such poets as Coleridge, Shelley, or Keats, he would—for

the purposes of any edition affecting to be complete—have put in everything he

could lay his hands upon, although he would always have preferred, for his own

reading, a compendium of the masterpieces. But, as regards himself individually,

personal sensitiveness gave him a different bias. He detested the very idea that

some of his boyish crudities (such as Sir Hugh the Heron , for which ingenuous

persons are willing to give some ten times the price of his Collected Works ) should

ever be brought forward. I therefore, in compiling the Collected Works , excluded

all such crudities; and to this day I would not publish, even in a casual and

scattered form, those writings of his which I believe he would have considered

essentially poor or bad.

intentionally jocular—which appear to me considerably removed from being bad

or poor, and which he himself would probably have thought admissible for eventual

printing, though not for publication during his lifetime, or as a portion of his solid

literary life-work. The pieces which I have here put together are of this kind.

They all belong to the days of his youth—the latest of them to 1853 or there–

abouts, when he completed his twenty-fifth year. I think that every one of them

has its value, whether on the ground of intrinsic merit, or as illustrating some

phase of his mental development and practice. I have grouped them together as

best I can, and added a few remarks by way of elucidation.

London, July 1898.

the first form of the composition which, under the title Ave , was published in

the volume Poems of 1870. The number of lines in this first form is 63.

Afterwards my brother enlarged the poem to 146 lines, giving it the title Ave ,

and the motto “Ego mater pulchræ delectionis et timoris et agnistionis, et

sancti spes.” In this second form I find the poem signed “H.H.H.,” which is

the same signature that he gave to the ballad of Sister Helen when that was

first published, towards 1854, in The Dusseldorf Artists' Annual , edited for

England by Mary Howitt. I apprehend that he must have offered to publish this

Ave also in the same annual; the copy of it which I possess is not in his own

“Writing on the Sand.”

“Writing on the Sand.”

From an unfinished water-colour by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in the

British Museum. handwriting, but (I think) in that of Miss Barbara Leigh Smith (Mrs. Bodichon),

who was very intimate with the Howitt family. In the Poems of 1870 the

composition is reduced from 146 to 112 lines; and, what between omissions and

alterations, seventy of the lines forming the Ave which I now present to the

reader passed under revision. Without at all calling in question the wisdom of

the course which my brother pursued in modifying the poem into the form that it

bears in his volume, I think that both the versions which I now print have their

individual attraction and interest, and a fair claim to be preserved.

and perhaps never will be;

but in this connexion I may

as well mention it—and I

could easily name some few

more, were there any occasion

for so doing. The heading

of the poem in question—

twenty-one stanzas of sextet

metre—is Sacred to the

Memory of Algernon R. G.

Stanhope, Natus est 1838,

obiit 1847. This was written

in September 1847, a date

later than that of The Blessed

Damozel . It is perhaps the

only poem which my brother

ever wrote “to order.” Our

family-friend Cavalier Mortara

knew something of this

Stanhope family, to the

Rossettis not known at all;

and he solicited my brother

to write some verses in com–

memoration of a beautiful

and promising boy, lately

deceased. The poem is by

no means amiss in its way,

but is decidedly inferior to

some other work of the same period; and my brother, when he had to consider

the question of publishing, never deigned a thought to this particular performance.

- “Mind'st thou not, when the twilight gone

- Left darkness in the house of John,”

subjects, a water-colour entitled The House of John. He may also observe the line—

- “Like to a thought of Raphaël,”

work. The same thing appears in another poem of a nearly similar date; and

this I quote with a view to showing that Dante Rossetti, when soon afterwards

to the lofty claims of the founder of the Roman School. I possess a fragment

in an early form of my brother's poem The Portrait —four stanzas. There is also

a complete copy, twelve stanzas, but differing greatly from the twelve which form

the published poem. It is called On Mary's Portrait, which I painted six years

ago , and its date may be 1847, or at latest 1848. Of course Dante Rossetti

never did paint any such portrait, and could not paint at all six years prior to

1848, nor was there any Mary to be painted. In the four-stanza version, one

of the stanzas is practically the same as in the printed form of the poem: the

other three are wholly different. The last of them (gracious in its way, though

juvenile) runs thus:—

- So along some grass-bank in Heaven,

- Mary the Virgin, going by,

- Seeth her servant Raphaël

- Laid in warm silence happily;

- Being but a little lovelier

- Since he hath reached the eternal year.

- She smiles; and he, as tho' she spoke,

- Feels thanked, and from his lifted toque

- His curls fall as he bends to her.

- Mother of the fair delight,

- From the azure standing white

- And looking golden in the light;—

- With the shadow of the Heaven-roof

- Upon thy hands lifted aloof,

- And a mystic quiet in thine eyes

- Born of the hush of Paradise,

- Seated beside the Ancient Three,

- Thyself a woman-Trinity—

- 10Being the dear daughter of God,

- Mother of Christ from stall to rood,

- And wife unto the Holy Ghost;—

- Oh, when our need is uttermost,

- And the sorrow we have seemeth to last,—

- Though the future falls not to the past

- In the race that the Great Cycle runs,

- Bethink thee of that olden once

- Wherein to such as death may strike

- Thou wert a sister, sisterlike.

- 20Yea, even thou, who reignest now

- Where the Angels are they that bow,—

- Thou, hardly to be looked upon

- By saints whose steps tread thro' the Sun,—

- Thou, the most greenly jubilant

- Of the leaves of the Threefold Plant,—

- Headstone of this humanity,

- Groundstone of the great Mystery,

- Fashioned like us, yet more than we.

- I think that at the furthest top

- 30My love just sees thee standing up

- Where the light of the Throne is bright;

- Unto the left, unto the right,

- The cherubim, order'd and join'd,

- Slope inward to a golden point,

- And from between the seraphim

- The glory cometh like a hymn:

- All is aquiet,—nothing stirs;

- The peace of nineteen hundred years

- Is within thee and without thee;

- 40And the Godshine falls about thee;

- And thy face looks from thy veil

- Sweetly and solemnly and well,

- Like to a thought of Raphaël.

- Oh, if that look can stoop so far,

- Let it reach down from star to star

- And try to see us where we are;

- For the griefs we weep came like swift death,

- But the slow comfort loitereth.

- Sometimes it even seems to us

- 50That we are overbold when thus

- We cry and hope we shall be heard;—

- Being much less than a short word,—

- Mere shadow that abideth not,—

- Dusty nothing, soon forgot.

- O Lady Mary, be not loth

- To listen,—thou whom the stars clothe!

- Bend thine ear, and pour back thine hair,

- And let our voice come to thee there

- Where, seeing, thou mayst not be seen;

- 60Help us a little, Mary Queen!

- Into the shadow thrust thy face,

- Bowing thee from the glory-place,

- Saint Mary the Virgin, full of grace!

Ego Mater pulchræ delectionis et timoris et agnistionis, et sancti spes.

- Mother of the Fair Delight,—

- An handmaid perfect in His sight

- Who made thy Blessing infinite,

- For generations of the earth

- Have called thee Blessed from thenceforth,—

- Now sitting with the Ancient Three,

- Thyself a woman-Trinity;

- Being the daughter of Great God,

- Mother of Christ from stall to rood,

- 10 And wife unto the Holy Ghost:—

- Oh, when our need is uttermost

- And the long sorrow seems to last,

- Then, though no future falls to past

- In the still course thy cycle runs,

- Bethink thee of that olden once

- Wherein to such as Death may strike

- Thou wert a sister, sisterlike:

- Yea, even thou, who reignest now

- Where angels veil their eyes and bow,—

- 20 Thou, scarcely to be looked upon

- By saints whose footsteps tread the sun,—

- Headstone of this humanity,

- Groundstone of the great Mystery,

- Fashioned like us, yet more than we.

- Mind'st thou not (when June's heavy breath

- Warmed the long days in Nazareth)

- That eve thou wentest forth to give

- Thy flowers some drink, that they might live

- One faint night more among the sands?

- 30 Far off the trees were as dark wands

- Against the fervid sky, wherefrom

- It seemed at length the heat must come

- Bodily down in fire: the sea,

- Behind, reached on eternally,

- Like an old music soothing sleep.

- Then gloried thy deep eyes, and deep

- Within thine heart the song waxt loud.

- It was to thee as though the cloud

- Which shuts the inner shrine from view

- 40 Were molten, and that God burned through:

- Until a folding sense like prayer,

- Which is, as God is, everywhere,

- Gathered about thee; and a voice

- Spake to thee without any noise,

- Being of the Silence: ‘Hail,’ it said,

- ‘Thou that art highly favoured;

- The Lord is with thee, here and now,

- Blessed among all women thou.’

- Ah! knew'st thou of the end, when first

- 50 That Babe was on thy bosom nurst?—

- Or when He tottered round thy knee

- Did thy great sorrow dawn on thee?—

- And through His boyhood, year by year

- Eating with thee the Passover,

- Didst thou discern confusedly

- That holier sacrament when He,

- The bitter cup about to quaff,

- Should break the bread and eat thereof?

- Or came not yet the knowledge, even,

- 60 Till on some night forecast in Heaven,

- Over thy threshold through the mirk

- He passed upon His Father's work?

- Or still was God's high secret kept?

- Nay but I think the whisper crept

- Like growth through childhood, and those sports

- 'Mid angels in the Temple-courts

- Awed thee with meanings unfulfilled;

- And that in girlhood something stilled

- Thy senses like the birth of light,

- 70 When thou hast trimmed thy lamp at night,

- Or washed thy garments in the stream;

- For to thy bed had come the dream

- That He was thine and thou wert His

- Who feeds among the field-lilies.

- Oh solemn shadow of the end

- In that wise spirit long contained!

- Oh awful end! and those unsaid

- Long years when It was finished!

- Mind'st thou not (when the twilight gone

- 80 Left darkness in the house of John)

- Between the naked window-bars

- That spacious vigil of the stars?

- For thou, a watcher even as they,

- Wouldst rise from where throughout the day

- Thou wroughtest raiment for His poor;

- And, finding the fixt terms endure

- Of day and night, which never brought

- Sounds of His coming chariot,

- Wouldst lift through cloud-waste unexplored

- 90 Those eyes which said, ‘How long, O Lord?’

- Then that disciple whom He loved,

- Well heeding, haply would be moved

- To ask thy blessing in His name;

- And thy thought and his thought, the same

- Though silent, then would clasp ye round

- To weep together,—tears long bound,

- Soft tears of patience, dumb and slow

- Yet, ‘Surely I come quickly,’—so

- He said, from life and death gone home.

- 100 Amen: even so, Lord Jesus, come!

- But oh what human tongue can speak

- That day when Michael came to break

- From the tired spirit, like a veil,

- Its covenant with Gabriel,

- Endured at length unto the end?

- What human thought can apprehend

- That mystery of motherhood

- When thy Beloved at length renewed

- The sweet communion severed,—

- 110 His left hand underneath thine head

- And His right hand embracing thee?—

- For henceforth thine abode must be,

- Beyond all mortal pains and plaints,

- The full assembly of the Saints.

- Is't Faith perchance, or Love, or Hope,

- Now lets me see thee standing up

- Where the light of the Throne is bright?

- Unto the left, unto the right,

- The cherubim, ordered and joined,

- 120 Float inward to a golden point,

- And from between the seraphim

- The glory cometh like a hymn.

- All is aquiet, nothing stirs;

- The peace of nineteen hundred years

- Is within thee and without thee,

- And the Godshine falls about thee.

- Oh if that look can stoop so far,

- It shall reach down from star to star

- And try to see us where we are;

- 130 For this our grief came swift as death,

- But the slow comfort loitereth.

- Sometimes it even seems to us

- That we are overbold when thus

- We cry and hope we shall be heard;

- Being surely less than a short word,—

- Mere shadow that abideth not,—

- A dusty nothing, soon forgot.

- Yet, Lady Mary, be not loth

- To listen, thou whom the stars clothe!

- 140 Bend thine ear, and pour back thine hair,

- And let our voice come to thee there

- Where, seeing, thou mayst not be seen;

- Help us a little, Mary Queen!

- Into the shadow lean thy face,

- Bowing thee from the secret place,

- Saint Mary Virgin, full of grace!

spoke thus in a published letter to William Allingham, November 22nd, 1860:—

“I never meant, I believe, to print the hymn.”

- On a fair Sabbath day, when His banquet is spread,

- It is pleasant to feast with my Lord:

- His stewards stand robed at the foot and the head

- Of the soul-filling, life-giving board.

- All the guests here had burthens; but by the King's grant

- We left them behind when we came;

- The burthen of wealth and the burthen of want,

- And even the burthen of shame.

- And oh, when we take them again at the gate,

- 10 Though still we must bear them awhile,

- Much smaller they'll seem in the lane that grows strait,

- And much lighter to lift at the stile.

- For that which is in us is life to the heart,

- Is dew to the soles of the feet,

- Fresh strength to the loins, giving ease from their smart,

- Warmth in frost, and a breeze in the heat.

- No feast where the belly alone hath its fill,—

- He gives me His body and blood;

- The blood and the body (I'll think of it still)

- 20 Of my Lord, which is Christ, which is God.

at any rate from its subject-matter. It is jotted down on the back of a

short poem dated 1849: I therefore assume it to belong to the same year. It

Pen-and-ink sketch of John Everett

Millais,

by Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

1850.

must certainly be his own composition, as there are

some cancellings and changes in it. One may infer

that Rossetti contemplated at this time erecting, when

opportunity might allow, some slight monumental

record of Blake.

Probably there is no character in which is so

much of

Shakespear himself as in Hamlet, except

in Falstaff.

- Dear friend, if there be any bond

- Which friendship wins not much beyond—

- So old and fond, since thought began—

- It may be that whose subtle span

- Binds Shakespear to an English man.

To the memory of William Blake, a Painter and Poet whose

greatness may be

named even here since it was equalled by

his goodness, this tablet is now

erected, ——years after his

death, at the age of sixty-eight, on August 12th,

1827, in

poverty and neglect, by one who honours his life and

works.

- All beauty to pourtray,

- Therein his duty lay,

- And still thro' toilsome strife

- Duty to him was life—

- Most thankful still that duty

- Lay in the paths of beauty.

during his little trip with Holman Hunt in the autumn of 1849; various other

things which he wrote during the same trip have already been published. The

following are characteristic, and to a great extent good. The opprobrious terms

applied to Correggio and Rubens are of course exaggerated to the extent of

silliness. They pertain to my brother's exoteric attitude as a “P.R.B.” That he

did not at that date sympathise with those phases of art which Correggio and

Rubens exemplify, and in a sense disliked their pictures, is a fact; but he even

then knew perfectly well that both these masters are among the great executants;

and only in his inner circle would he, for purposes of defiance and of burlesque,

and inspirited by certain utterances of Blake, have pretended not to know as

much. The opening of the sonnet At the Station of the Versailles Railway is

of course an undisguised imitation from Tennyson's Godiva.

- These coins that jostle on my hand do own

- No single image: each name here and date

- Denoting in man's consciousness and state

- New change. In some, the face is clearly known,—

- In others marred. The badge of that old throne

- Of Kings is on the obverse; or this sign

- Which says, “I France am all—lo, I am mine!”

- Or else the Eagle that dared soar alone.

- Even as these coins, so are these lives and years

- 10Mixed and bewildered; yet hath each of them

- No less its part in what is come to be

- For France. Empire, Republic, Monarchy,—

- Each clamours or keeps silence in her name,

- And lives within the pulse that now is hers.

- I waited for the train unto Versailles.

- I hung with bonnes and gamins on the bridge

- Watching the gravelled road where, ridge with ridge,

- Under black arches gleam the iron rails

- Clear in the darkness, till the darkness fails

- And they press on to light again—again

- To reach the dark. I waited for the train

- Unto Versailles; I leaned over the bridge,

- And wondered, cold and drowsy, why the knave

- 10Claude is in worship; and why (sense apart)

- Rubens preferred a mustard vehicle.

- The wind veered short. I turned upon my heel

- Saying, “Correggio was a toad”; then gave

- Three dizzy yawns, and knew not of the Art.

- In a dull swiftness we are carried by

- With bodies left at sway and shaking knees.

- The wind has ceased, or is a feeble breeze

- Warm in the sun. The leaves are not yet dry

- From yesterday's dense rain. All, low and high

- A strong green country; but, among its trees,

- Ruddy and thin with Autumn. After these

- There is the city still before the sky.

- Versailles is reached. Pass we the galleries

- 10And seek the gardens. A great silence here,

- Thro' the long planted alleys, to the long

- Distance of water. More than tune or song,

- Silence shall grow to awe within thine eyes,

- Till thy thought swim with the blue turning sphere.

- “ Messieurs, le Dieu des peintres”: We felt odd:

- 'Twas Rubens, sculptured. A mean florid church

- Was the next thing we saw,—from vane to porch

- His drivel. The museum: as we trod

- Its steps, his bust held us at bay. The clod

- Has slosh by miles along the wall within.

- (“I say, I somehow feel my gorge begin

- To rise”)—His chair in a glass case, by God!

- . . . . To the Cathedral. Here too the vile snob

- 10Has fouled in every corner. (“Wherefore brave

- Our fate? Let's go.”) There is a monument

- We pass. “Messieurs, you tread upon the grave

- Of the great Rubens.” “Well, that's one good job!

- What time this evening is the train for Ghent?”

- We are upon the Scheldt. We know we move,

- Because there is a floating at our eyes,

- Whatso they seek; and because all the things

- Which on our outset were distinct and large

- Are smaller and much weaker and quite grey,

- And at last gone from us. No motion else.

- We are upon the road. The thin swift moon

- Runs with the running clouds that are the sky,

- And with the running water runs—at whiles

- 10Weak 'neath the film and heavy growth of reeds.

- The country swims with motion. Time itself

- Is consciously beside us, and perceived.

- Our speed is such, the sparks our engine leaves

- Are burning after the whole train has passed.

- The darkness is a tumult. We tear on,

- The roll behind us and the cry before,

- Constantly, in a lull of intense speed

- And thunder. Any other sound is known

- Merely by sight. The shrubs, the trees your eye

- 20Scans for their growth, are far along in haze.

- The sky has lost its clouds, and lies away

- Oppressively at calm; the moon has failed;

- Our speed has set the wind against us. Now

- Our engine's heat is fiercer and flings up

- Great glares alongside. Wind and steam and speed

- And clamour and the night. We are in Ghent.

- The city's steeple-towers remove away

- Each singly; as each vain infatuate faith

- Leaves God in heaven and passes. A mere breath

- Each soon appears, so far. Yet that which lay

- The first is now scarce further or more grey

- Than is the last. Now all are wholly gone.

- The sunless sky has not once had the sun

- Since the first weak beginning of the day.

- The air falls back as the wind finishes,

- 10And the clouds stagnate; on the water's face

- The current moves along but is not stirr'd.

- There is no branch that thrills with any bird.

- Lo, Winter must possess the earth a space,

- And have his will upon the extreme seas.

- On landing, the first voice one hears is from

- An English police-constable; a man

- Respectful, conscious that at need he can

- Enforce respect. Our custom-house at home

- Strict too, but quiet. Not the foul-mouthed scum

- Of passport-mongers who in Paris still

- Preserve the Reign of Terror; not the till

- Where the King haggles, all through Belgium.

- The country somehow seems in earnest here,

- 10Grave and sufficient:— England, so to speak;

- No other word will make the thing as clear.

- “Ah! habit,” you exclaim, “and prejudice!”

- If so, so be it. One don't care to shriek,

- “Sir, this shall be!” But one believes it is.

much in the habit of writing sonnets to bouts-rimés. He and I would sit together,

I giving him the rhymes for fourteen lines, and he giving me other rhymes for

another fourteen. The practice may have lasted from a late date in 1847 to an

early date in 1849; hardly beyond these limits. I have found nine of his

sonnets written in this way (also nine of my own), neatly copied out, and a few

others as well. The series copied out was at one time much longer: the latest

progressive number applicable to his set of sonnets thus preserved is 43. The

one named Another Love took eight minutes in composing. I present a brace of

sonnets just as specimens—not as literary achievements. A judicious reader will

not expect to find much force of compacted thought in a bouts-rimés sonnet; in

those by my brother he will perhaps discern, along with facility of touch, a

certain stress of romantic impulse or suggestion, which is as much as I care to

claim for them, though I think The World's Doing may be called a good thing.

- Of her I thought who now is gone so far:

- And, the thought passing over, to fall thence

- Was like a fall from spirit into sense,

- Or from the heaven of heavens to sun and star.

- None other than Love's self ordained the bar

- 'Twixt her and me; so that if, going hence,

- I met her, it would only seem a dense

- Film of the brain—just nought, as phantoms are.

- Now, when I passed your threshold, and came in,

- 10And glanced where you were sitting, and did see

- Your tresses in these braids, and your hands thus,—

- I knew that other figure, grieved and thin,

- That seemed there, yea that was there, could not be—

- Though like God's wrath it stood dividing us.

- One scarce would think that we can be the same

- Who used, in those first childish Junes, to creep

- With held breath through the underwood, and leap

- Outside into the sun. Since this mine aim

- Took me unto itself, the joy which came

- Into my eyes at once sits hushed and deep;

- Nor even the sorrow moans, but falls asleep

- And has ill dreams. For you—your very name

- Seems altered in mine ears, and cannot send

- 10Heat through my heart, as in those days afar

- Wherein we lived indeed with the real life.

- Yet why should we feel shame, my dear sweet friend?

- Are they most honoured who without a scar

- Pace forth, all trim and fresh, from the splashed strife?

Dante Gabriel Rossetti . Here, however, I think it may find a suitable place. It

relates of course to the Chartist or pseudo-Chartist meetings which formed a

transitory alarm to Londoners in the early months of 1848. Readers whose

memories go back to that date will understand the references to Moses and Son,

puny John (Russell), Cochrane, G. W. M. Reynolds and Reynolds's Miscellany , etc.:

for other readers they seem hardly worth explaining. It may be as well to say

that my brother had no real grounded objection to the principles of “The

People's Charter”—I dare say he never knew accurately what they were: but he

disliked bluster and blusterers, noise-mongers and noise, and he has here indulged

himself in a fling at them.

“Some unprincipled persons endeavour to impose upon the

public by such phrases as ‘It's all one,’ ‘It's the

same

concern,’ etc.”

- Ho ye that nothing have to lose! ho rouse ye, one and all!

- Come from the sinks of the New Cut, the purlieus of Vauxhall!

- Did ye not hear the mighty sound boom by ye as it went—

- The Seven Dials strike the hour of man's enfranchisement?

- Ho cock your eyes, my gallant pals, and swing your heavy staves:

- Remember—Kings and Queens being out, the great cards will be Knaves.

- And when the pack is ours—oh then at what a slapping pace

- Shall the tens be trodden down to five, and the fives kicked down to ace!

- It was but yesterday the Times and Post and Telegraph

- 10Told how from France King Louy-Phil. was shaken out like chaff;

- To-morrow, boys, the National, the Siècle, and the Débats,

- Shall have to tell the self-same tale of “La Reine Victoria.”

- What! shall our incomes we've not got be taxed by puny John?

- Shall the policeman keep Time back by bidding us move on?

- Shall we too follow in the steps of that poor sneak Cochrane?

- Shall it be said, ‘They came, they saw,—and bolted back again’?

- Not so! albeit great men have been among us, and are floor'd—

- (Frost, Williams, Jones, and other ones who now reside abroad)—

- Among the master-spirits of the age there still are those

- 20Who'll pick up fame—even though, when smelt, it makes men hold the nose.

- What ho there! clear the way! make room for him, the “fly” and wise,

- Who wrote in mystic grammar about London's “Mysteries,”—

- For him who takes a proud delight to wallow in our kennels,—

- For Mr. A. B. C. D. E. F. G. M. W. Reynolds!

- Come, hoist him up! his pockets will afford convenient hold

- To grab him by; and, if inside there silver is or gold,

- And should it be found sticking to our hands when they're drawn out,

- Why, 'twere a chance not fair to say ill-natured things about.

- Silence! Hear, hear! He says that we're the sovereign people, we!

- 30And now? And now he states the fact that one and one make three!

- Now he makes casual mention of a certain Miscellany!

- He says that he's the editor! He says it costs a penny!

- O thou great Spirit of the World! shall not the lofty things

- He saith be borne unto all time for noble lessonings?

- Shall not our sons tell to their sons what we could do and dare

- In this the great year Forty-eight and in Trafalgar Square?

- Swathed in foul wood, yon column stood 'mid London's thousand marts;

- And at their wine Committeemen grinned as they drank “The Arts”;

- But our good flint-stones have bowled down each poster-hidden board,

- 40And from their hoarded malice our strong hands have stript the hoard.

- Yon column is a prouder thing than Cæsar's triumph-arch!

- It shall be called “The Column of the Glorious Days of March!”

- And stonemasons' apprentices shall grow rich men therewith,

- By contract-chiselling the names of Jones and Brown and Smith.

- Upon what point of London, say, shall our next vengeance burst?

- Shall the Exchange, or Parliament, be immolated first?

- Which of the Squares shall we burn down?—which of the Palaces?

- ( The speaker is nailed by a policeman )

- Oh please sir, don't! It isn't me. It's him. Oh don't, sir, please!

of Mrs. Stowe's (to my thinking) fine story of Uncle Tom's Cabin. The nigger

song of Uncle Ned, which gives occasion to the parody, was also copied out by

Maria: I retain it here for comparison, though I suppose it is still (as at that

remote date) perfectly well known. There is likewise a pen-and-ink sketch: it is

not exactly in the style generally associated with the name of Dante Rossetti, and

I reproduce it. He professes to have tried to read Uncle Tom, and failed; this

may be true, or may be a poetic fiction. I have no recollection of his having

really been familiar with the story in any degree. Uncle Tom was known throughout

the length and breadth of England as early as 1852, and I suppose the parody

was written in 1852, or else 1853. Carlyle's Occasional Discourse on the Nigger

Question (which amused my brother exceedingly, and in some sense convinced him)

had been published in 1849, and was his main incitement towards any utterance

about “niggers.”

- “Dere was an old nigger, and him name was Uncle Ned,

- And him died long long ago—

- Him hab no hair on de top of him head,

- In de place whar de wool ought to grow.

- Den hang up de fiddle and de bow,

- And lay down de shovel and de hoe:

- For dere's no more work for poor old Ned—

- He am gone whar de good darky go.

- “Him fingers was long as de cane in de brake,

- 10 And him had no eyes for to see;

- And him hab no teeth for to eat a corn-cake,

- So him hab to let a corn-cake be.

- Den hang up, etc.

- “It was a cold morning when Uncle Ned died,

- And de tears down Massa's cheeks fell like rain;

- For him know bery well, when him lay him in de ground,

- Dat him nebber see him like again.

- Den hang up, etc.”

- Dere was an old nigger, and him name was Uncle Tom,

- And him tale was rather slow;

- Me try to read de whole, but me only read some,

- Because me found it no go.

- Den hang up de author Mrs. Stowe,

- And kick de volume wid your toe—

- And dere's no more public for poor Uncle Tom,

- He am gone whar de trunk-lining go.

- Him tale dribbles on and on widout a break,

- 10 Till you hab no eyes for to see;

- When I reached Chapter 4 I had got a headache,

- So I had to let Chapter 4 be.

- Den hang up, etc.,

- De demand one fine morning for Uncle Tom died,

- De tears down Mrs. Stowe's face ran like rain;

- For she knew berry well, now dey'd laid him on de shelf,

- Dat she'd neber get a publisher again.

- Den hang up, etc.”

story gets fairly started. As such, I omitted it when I was compiling my brother's

Collected Works , but I think well to insert it here. The tone of writing, proper to

the supposed author, a “legitimate” actor, seems to be well sustained. I forget

what the gist of the story was to have been: certainly the devil was to bear

some part in it. The date of the fragment is dubious to me; but I think it was

later, rather than earlier, than St. Agnes of Intercession , written in 1849-50. I con–

sider that my brother's incitement towards writing a story about an Actor and the

Devil arose partly from his reading some years previously, in Hood's Magazine, a

very effective tale about the Devil acting his own part in some piece of diablerie

such as Der Freischütz. We never knew who the author of that tale may have

been.

Pen-and-ink sketch of “Uncle Tom,” by Dante

Gabriel Rossetti.

will derive no accession of credit from my stating at the outset that I am a public

actor,—one, in fact, whose very life is passed in the endeavour to identify himself with

fictitious characters and situations, and whose most consummate triumph would be the

bringing his audience to believe, if only for a single moment, that the events going

forward under their eyes were of spontaneous occurrence. Indeed, I cannot but look

upon this fact of my profession as calculated to be so seriously detrimental to a belief

in circumstances which I know to have really occurred that I should have considered

myself at liberty to suppress it, had it not been inextricably wound up with the very

warp and woof of my story. It therefore only remains for me to record on my own

behalf that protest which conscious truth has a right to oppose to all prejudice, based

on any grounds whatsoever. At the same time I would remind my reader that the very

improbability of the matters I shall narrate ought by rights to be counted as a plea in

my favour; since, being fully alive to the disadvantages under which I labour, I should,

if inclined to deceive, have at least selected a story more adapted for purposes of

deception, and could scarcely be supposed to rush with my eyes open upon the

humiliating result of acting like a fool and being thought to act like a knave.

to the legitimate drama, in which I have enjoyed a large share of public favour, and

now, towards the close of my career, may even consider myself celebrated. I have no

wish to speak harshly of those who have arisen in the course of my career, and who

have endeavoured to introduce new theories connected with parts on which I had

long before formed and pursued my own opinion, from which I may add that I have

not, at any time in the fluctuations of public taste, seen occasion to deviate. I fear,

indeed, that the days when the embodiment of tragedy on the stage was undesecrated

Portrait of Miss Siddal.

From a

drawing by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

(1860).

by a study of the petty actualities of common life are passed for ever. I at least

have to the last upheld my principles as an actor, and can afford to treat certain

recent criticisms with silent contempt. The strange passage in my life which I am

about to relate is commonly connected in my mind with the one occasion on which

I was weak enough to step down from the pinnacles of High Art, and seem to

bestow my sanction on the monstrosities of the modern drama. The mysterious

and awful circumstance (for I can call it by no other name) to which I allude might,

I think, not unjustly be regarded as a judgment upon me for this single concession to a

perverted taste.

saying that he had “been reading up all manner of old romaunts, to pitch upon

stunning words for poetry.” I have found some lists of words in his handwriting

which seem to belong to this quest; many of them, however, appear hardly to be

such words as would be found in old romaunts. In several instances he gives

definitions, in others not. I recognise in these lists various words which appear

passim in my brother's poems. Here are a few specimens of those which he

noted down:—

fat-kidneyed, fat-witted, fleshquake, flexile, foolhappy, frog-grass, frog-lettuce, gairish,

gonfalon, gorbellish, gracile, granulous, grogram, hipwort, honeywort, intercalary, ironwort,

jacent, jas-hawk, knee-tribute, lass-lorn, lunary, lustral, macerate, madwort, plenipotence,

acrook, anelace, aughtwhere, barm-cloth, gipsire, guerdonless, letter-lore, pennoncel,

primerole, recreandise, shrift-father, soothfastness, shent, virelay, Mahometrie, cautelous,

dern, eldrich, angelot, chanterie, cherishance, citole, cumber-world, creance, foreweeting,

laureole, moonwort, novelries, trifulcate, untressed, cittern, somedeal, vernage-wine,

eagle-heron, woodwale, chevesaile, trenchpayne, umbrere, aeromancy, liverwort, alkanet,

birthwort, crimosin, empusa, flexuous, franion, felwort, grisamber, jack-a-lent, jobbernowl,

musk-melon.”