Note: Text is printed in gold lettering with an inverted triangle of decorative

foliage below it.

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

Note: Inside the front cover is a bookplate which reads “ex

libris W. L. Phillips.”

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI

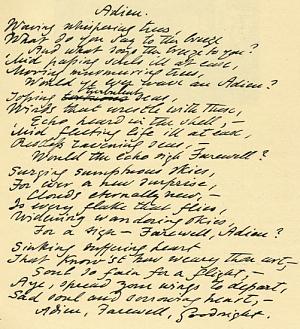

BY CHRISTINA ROSSETTI

December, 1856

-

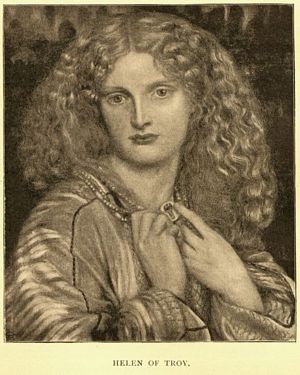

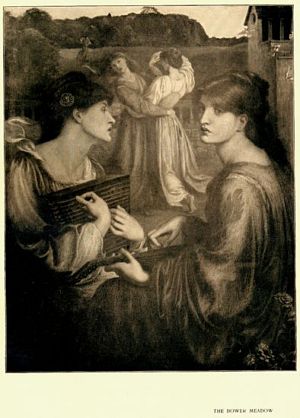

ONE face looks out from all his canvases,

-

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

-

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

-

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

-

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

-

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

-

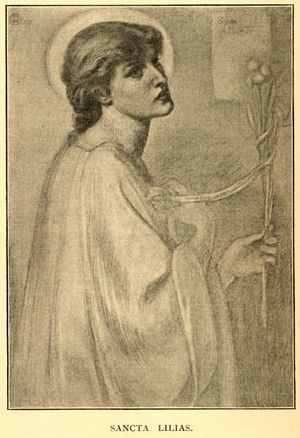

A saint, an angel—every canvas means

-

The one same meaning, neither more nor less.

-

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

-

10

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

-

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

-

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

-

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

-

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

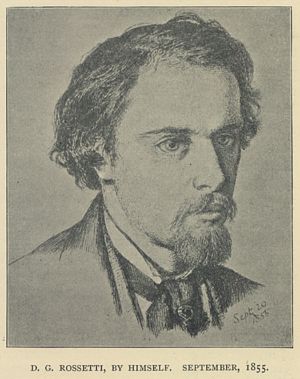

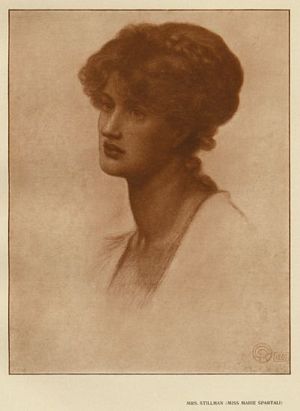

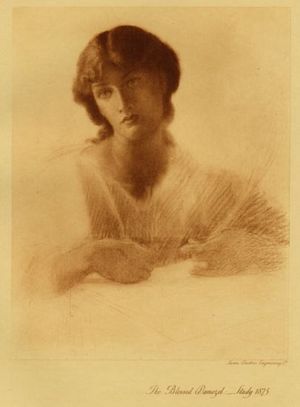

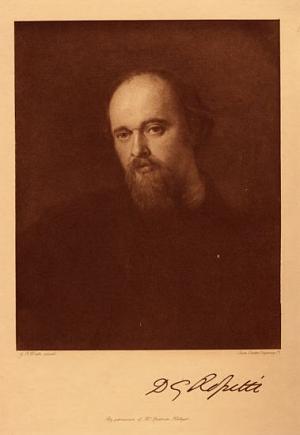

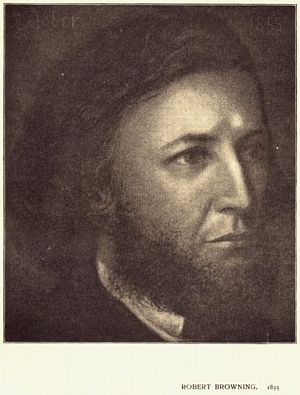

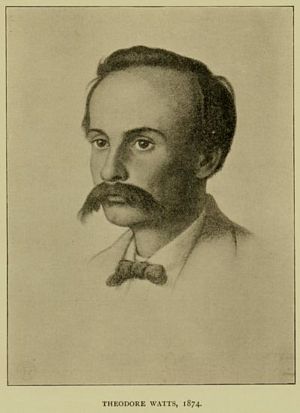

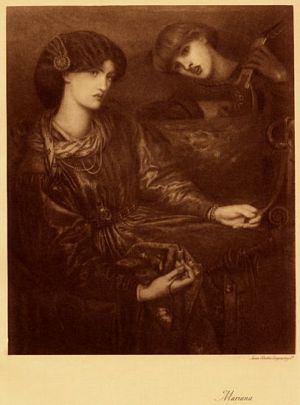

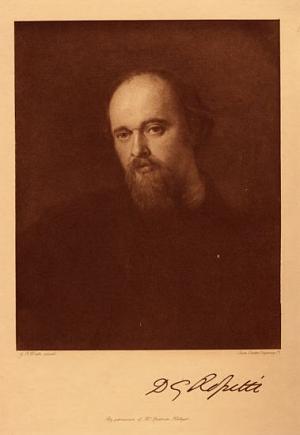

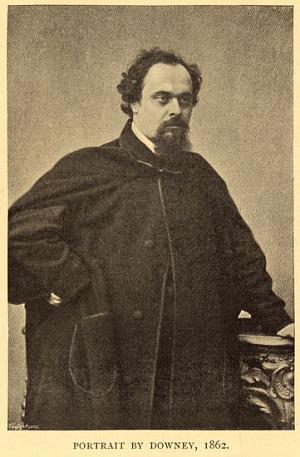

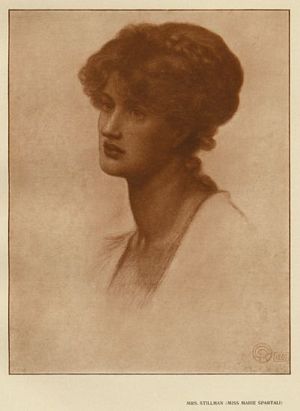

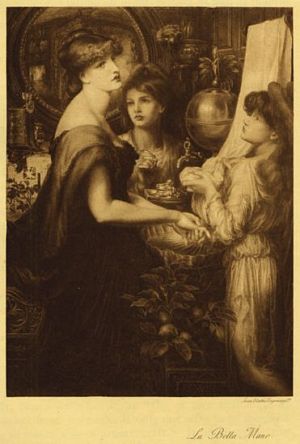

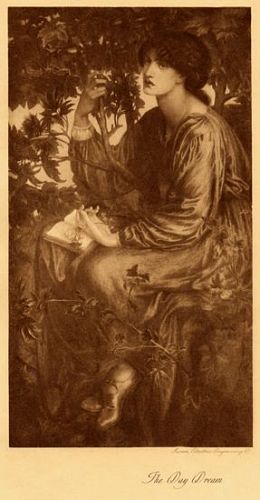

G.F. Watts, pinxit. Swan Electric Engraving C

o.

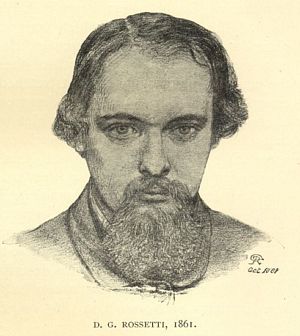

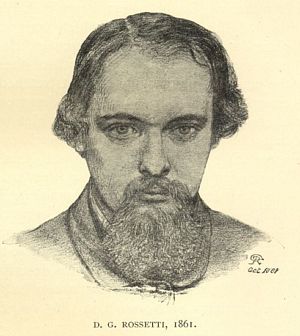

D G Rossetti

By permission of M

r.

Frederick Hollyer

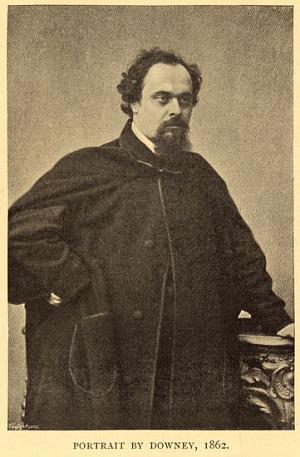

Figure: Sepia tone half-length portrait of a mature Dante Gabriel Rossetti

with his head turned slightly towards his right. Marillier reproduces a

facsimile of DGR's autograph below this picture.

Note: Rossetti's name is printed in red ink.

DANTE GABRIEL

ROSSETTI

AN ILLUSTRATED MEMORIAL OF HIS

ART AND LIFE

by

H. C. MARILLIER

George Bell & Sons

Figure: Imprint of George Bell & Sons publishers.

LONDON

GEORGE BELL AND SONS

1899

CHISWICK PRESS:—CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

HAVING been asked more than once if I was compiling a life of

Rossetti, I think it well to disclaim at the outset any such presumptuous

intention. A life of Rossetti, in the full sense of the word, could only be

written by one who was intimately and sympathetically associated with his work

during the major portion of his career; and of the very few who could have

undertaken the task some are no longer alive, whilst others have either

abandoned or postponed it until too late. For this reason we can hardly expect

now to have a life of this great and most original genius, written by anyone

with enough knowledge to interpret his many-coloured personality, yet

sufficiently disinterested to form a critical estimate of his true position and

influence.

Biographical works and data there are in profusion. The admirably conscientious

labours of Mr. William Michael Rossetti have resulted in placing before the

public copious records of the painter's external life, and of his private life

as well so far as it is revealed in letters to the members of his family. What

these do not give us is the man in relation to his work, and what they do give

us is not always strictly important. Nevertheless they constitute the most

valuable body of materials yet published, and no biographer could affect to

disregard them. They have been supplemented recently by the publication of

Ruskin's letters to Rossetti and Rossetti's letters to William Allingham, both

immensely interesting to students of the subject, but not by any means

exhaustive of the periods they cover. The only other sources of information that

seem to me worth mentioning are Mr. William Sharp's memoir, which would have been

better had it been less hastily compiled; Mr. Joseph Knight's little volume in the “Great Writers” series, dealing chiefly with the poems; Mr. W. M. Rossetti's

chronological record called “

Dante Gabriel Rossetti as Designer and Writer”; William Bell Scott's “

Autobiographical Notes,” compiled when the author

was too much embittered to write fairly; and Mr. F. G.

Stephens's handy

monograph in

the “Portfolio” series

. In addition might

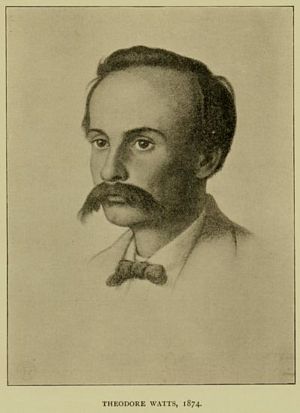

be mentioned Mr. Watts-Dunton's article in the “Encyclopædia

Brittanica.” There are of course many other books, and much

periodical literature dealing with Rossetti, but, with the single exception of

Mr. Holman Hunt's articles in the “Contemporary" of 1886 on the

“Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood,” these are not of great account.

One or two who claim to have written with intimate knowledge of their subject

labour under the disadvantage of not having known Rossetti until the latter

clouded years of his life, when his vigour and health were impaired, and he had

apparently lost the power of personal discrimination.

Of the materials which I have mentioned it would be ungrateful to complain,

seeing that as occasion demanded I have used or borrowed from most of them. I

must, however, say that careful research has not always tended to confirm the

information they afforded, and I may claim, I think, for this memoir that it

will be found correct on many points where errors previously existed. Three of

the above-named authorities, Mr. Sharp, Mr. Knight, and Mr. W. M. Rossetti, have

published catalogues or lists of Rossetti's pictures, giving dates and a few

other scanty particulars. Mr. Rossetti's list is certainly by far the best of

these, though not itself complete, the two earlier ones being almost useless now

for purposes of reference. I say this with no intention of disparagement, for

Mr. Sharp's list was a wonderful one to have compiled in the time allowed him;

and he had no previous data to work on, whereas I have had three lists to

collate and check, and possibly better opportunities of acquiring information.

In addition I have received much help with some of the more tangled problems

both from Mr. Rossetti and from Mr. Fairfax Murray, the latter of whom is

recognized as an expert in all matters connected with Rossetti's work. To Mr.

Murray moreover I am indebted for kindly checking the list of works and dates

which appears as an appendix to this volume, as well as for revising some of the

proofs. What use I have made of the assistance so generously given is my own

affair, and for this I alone am answerable. In acknowledging the benefit I do

not wish to alienate the responsibility.

What I have aimed at chiefly is to interweave a simple account of the painter's

life with a detailed chronological record of his artistic work. In this way, by

following certain broad divisions, a fairly continuous narrative is made

possible without jumbling up

pictures and incidents too confusedly. In dealing

with the pictures in the text I have followed a system which I think should be

found useful, as I myself have found the lack of it in other books somewhat

irritating; namely, I have grouped under the first, or sometimes under the most

important version of any particular subject, a list of all the other versions

and replicas which exist of it. These versions and replicas are then referred to

again briefly or in detail as may be under the different years to which they

belong. Some such system is absolutely necessary in dealing with Rossetti's

work, for the multitude of replicas and variants is bewildering, and most of the

errors which I have encountered have been due to confusion arising on this

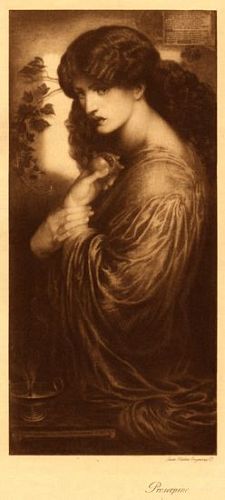

account. As an instance of the kind of tangle met with, who could foresee such a

confusion of dates and pictures as exists in the case of the

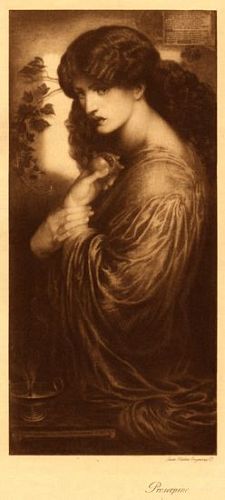

Proserpine

subject, or (without personal knowledge of the facts) understand the

complicated changes in the history of the

Dante and Beatrice

panels, given in this book, I believe, for the first time.

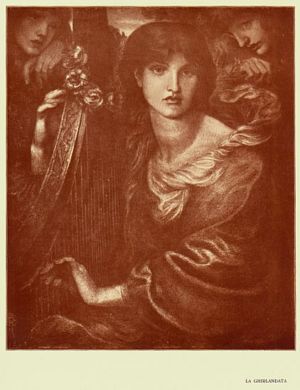

Whilst trying to compile a record of Rossetti's work which should be

comprehensive, accurate, and useful as a work of reference, I have not forgotten

that essentially it was a picture book that was wanted. In respect of the

illustrations, moreover, I can speak with greater freedom; and first, it is

pleasant to acknowlege that almost without exception the owners of Rossetti's

pictures have courteously allowed them to be reproduced, and have given special

facilities for photographing them. In some cases this was no ordinary

politeness, but a very generous concession, involving a violation of fixed

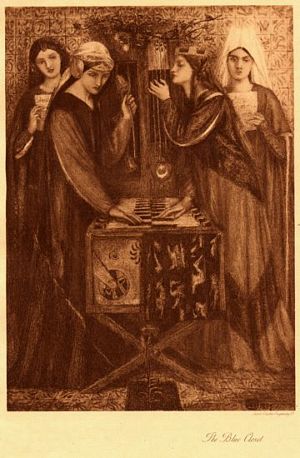

principles. Mr. Rae, it is well known, has for many years disapproved most

strongly of indiscriminate reproduction, and has refused all applications to let

his pictures be photographed for such a purpose, the only exceptions being when

he allowed Mr. Quilter to reproduce

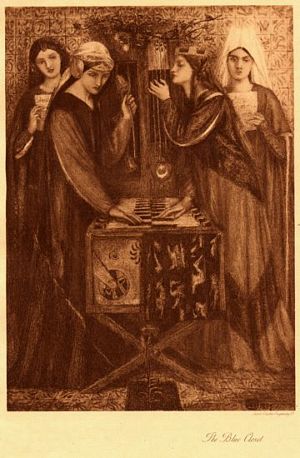

The Blue Closet

in “Preferences,” and Mr. Stephens to include

a few small subjects in his

already mentioned monograph done for “ The

Portfolio.” I cannot, therefore, express my obligation to him

sufficiently strongly for placing his magnificent collection at my disposal, and

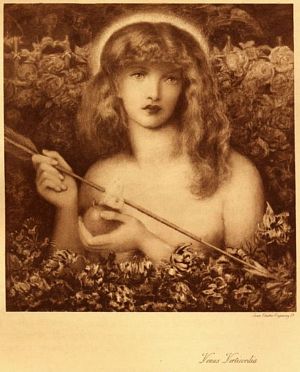

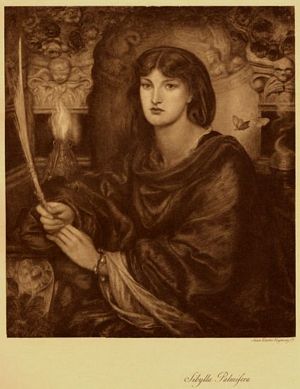

allowing me to reproduce eleven of his pictures; namely,

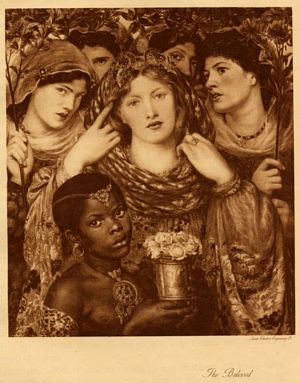

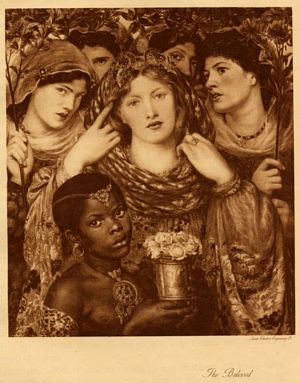

The Beloved

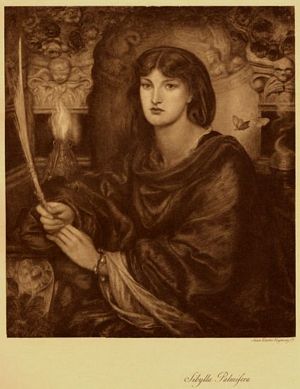

,

Sibylla Palmifera

,

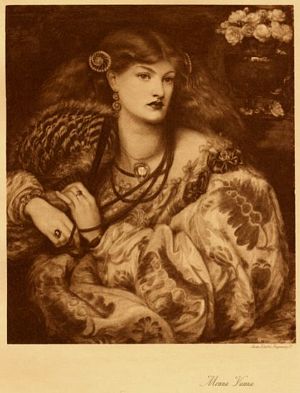

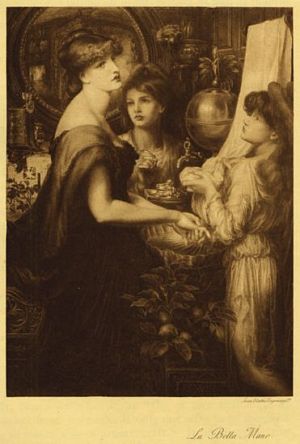

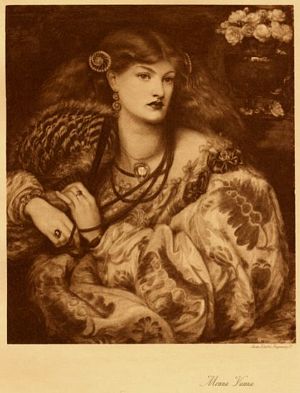

Monna Vanna

,

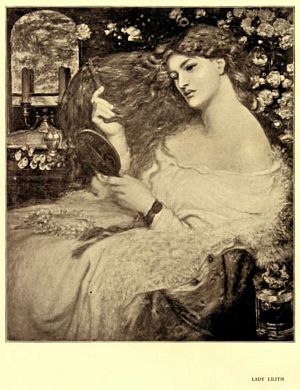

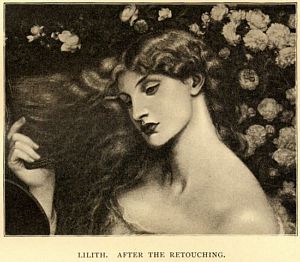

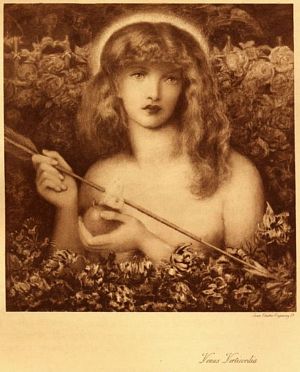

Venus Verticordia

,

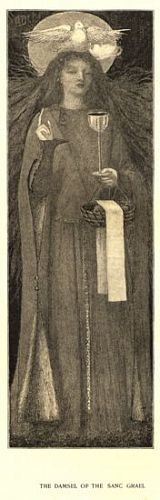

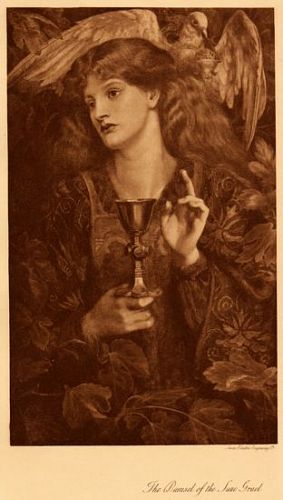

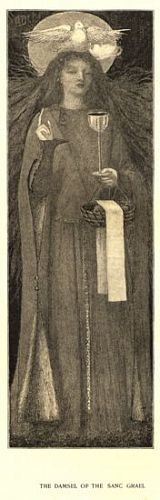

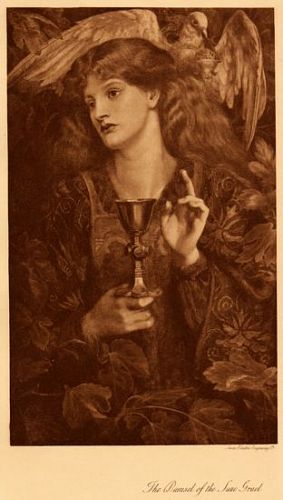

The Damsel of the Sanc Grael

(both the large

oil and

the little

water-colour),

The Blue Closet

,

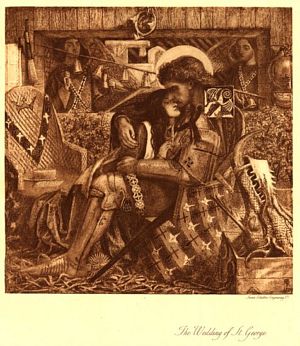

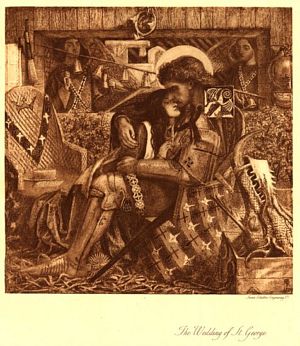

The Wedding of St. George

,

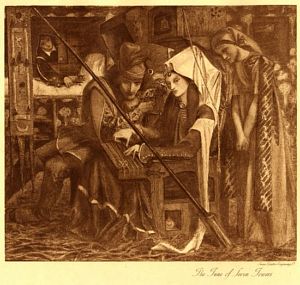

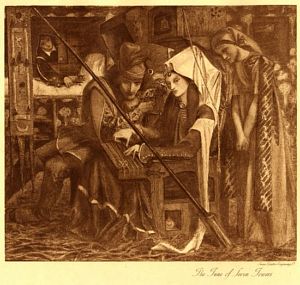

The Tune of Seven Towers

, the early pen-and-ink diptych of

Il Saluto di Beatrice

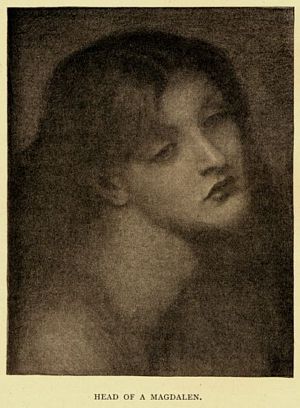

, and the beautiful crayon head of a

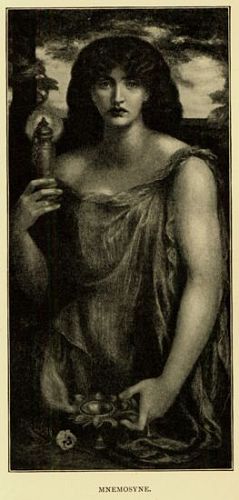

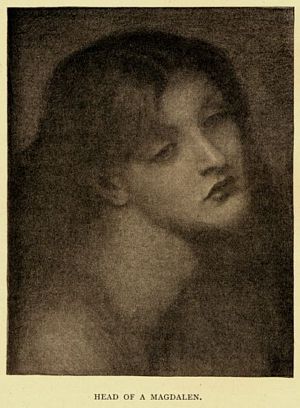

Magdalen

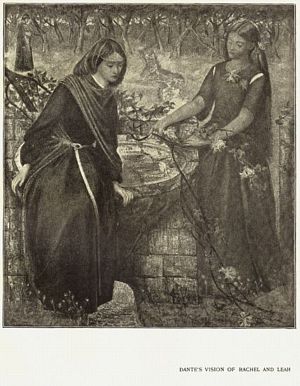

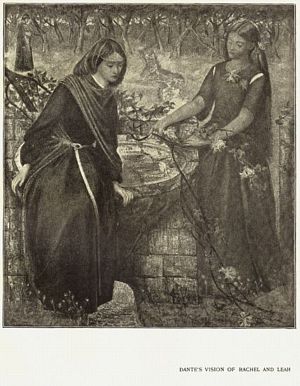

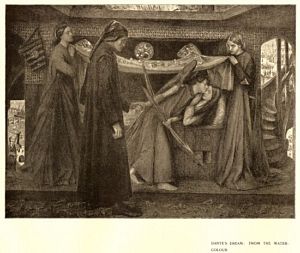

. Mr. Beresford Heaton, whose objections were almost

equally invincible, has at the last moment allowed

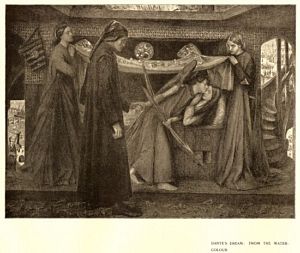

me to include the charming early water-colour

Dante's Dream

and

The Vision of Rachel and Leah

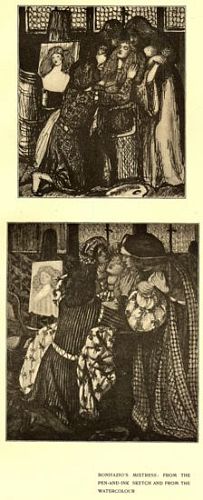

from his collection. Mr. Fairfax Murray has been not less generous in

allowing his drawings to be reproduced than in helping me with facts, and though

there are one or two treasures that he has withheld for special reasons, I am

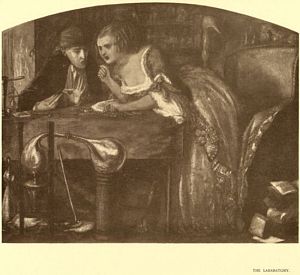

indebted to him for permission to include

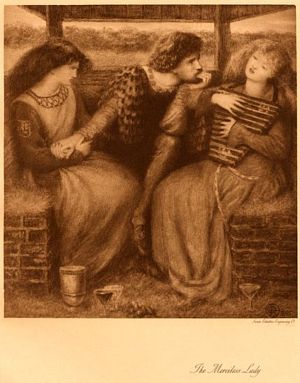

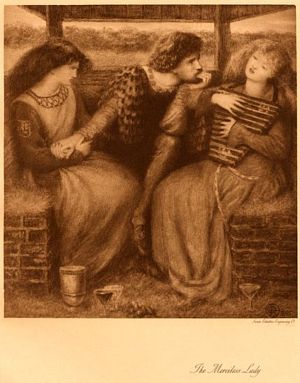

The Merciless Lady

,

Dr. Johnson at the Mitre

,

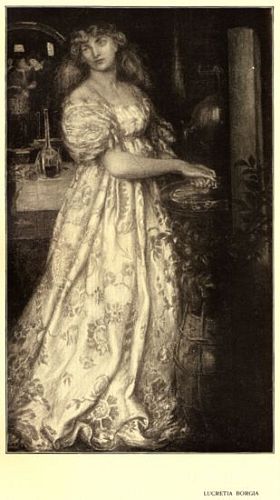

The Laboratory

,

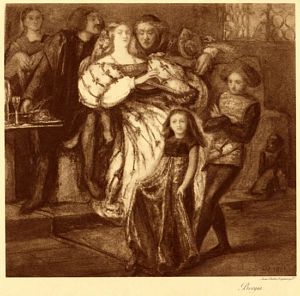

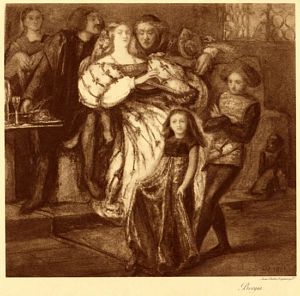

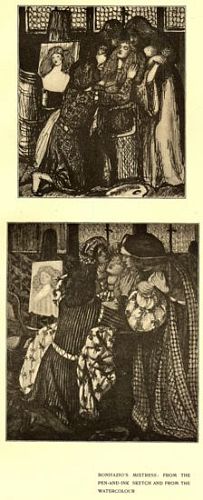

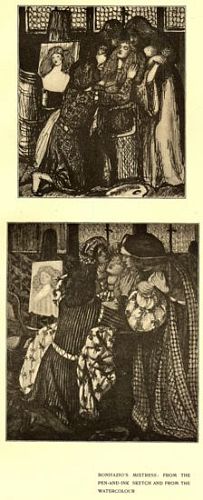

Bonifazio's Mistress

, with the

pen-and-ink

study

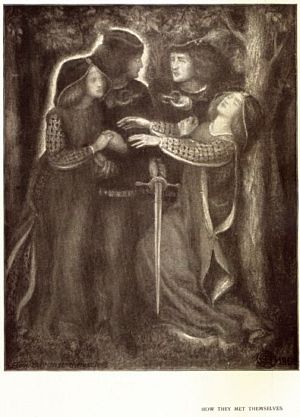

,

A Fight for a Woman

, the early sketch called

Genevieve

, a pencil drawing for

Mary in the House of John

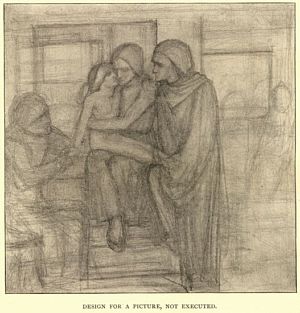

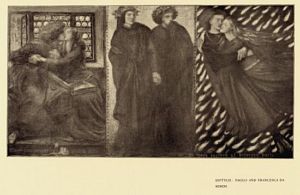

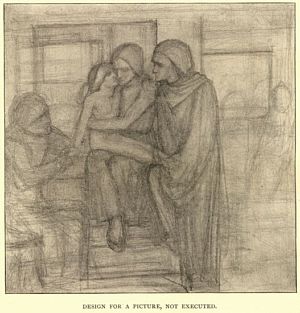

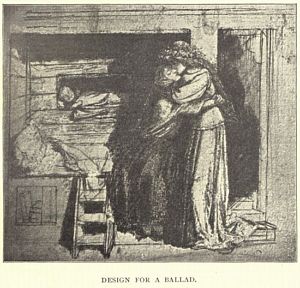

, and several minor items, including some designs for pictures never

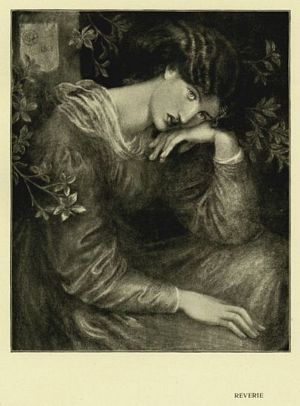

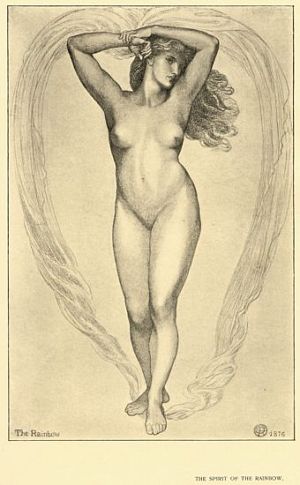

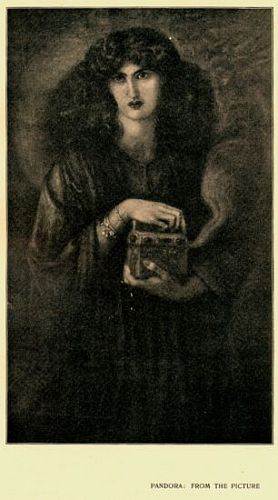

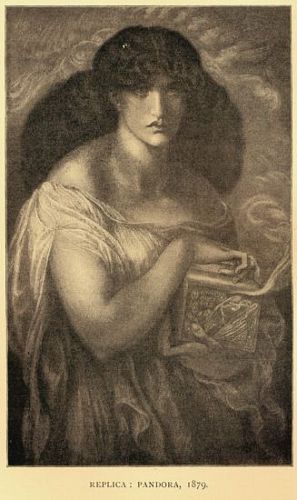

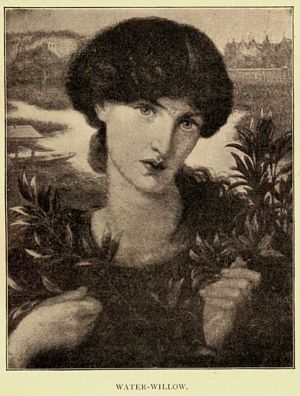

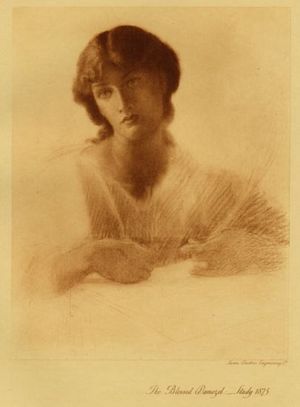

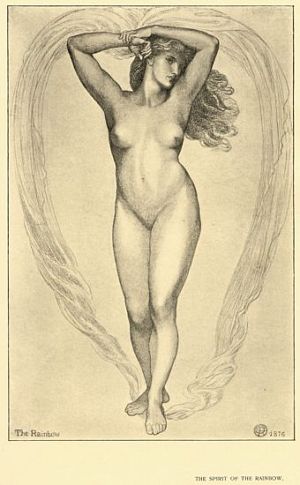

reproduced before. Mr. Watts-Dunton has allowed me to include

The Spirit of the Rainbow

, Rossetti's one nude figure, which has never before been given, as well

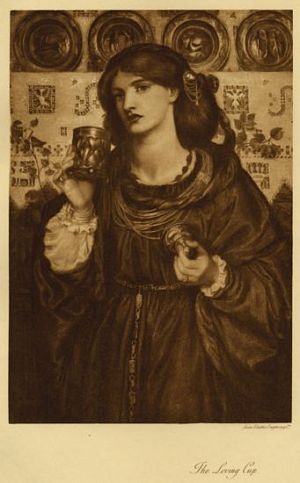

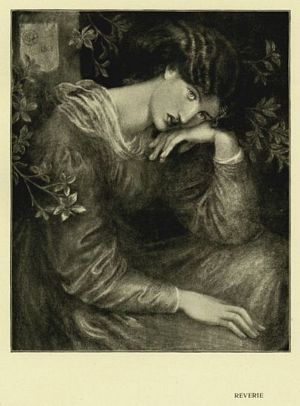

as his

Reverie

,

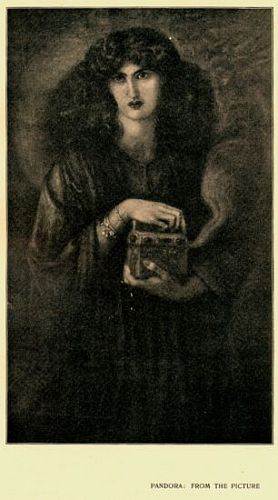

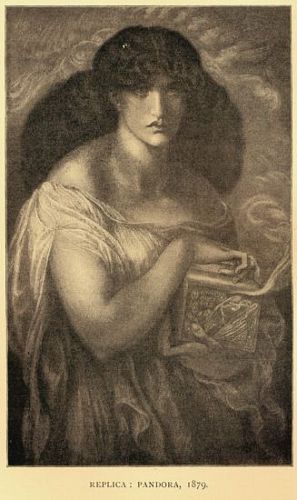

Pandora

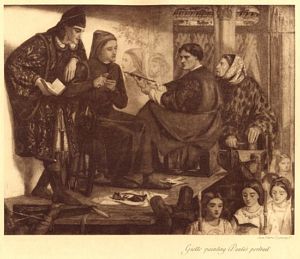

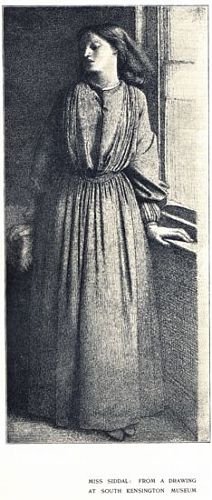

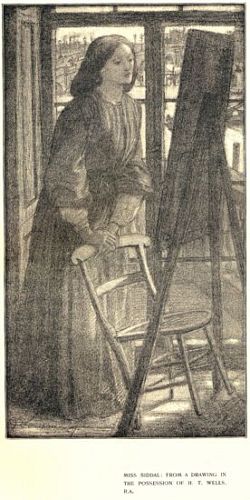

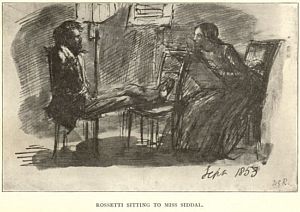

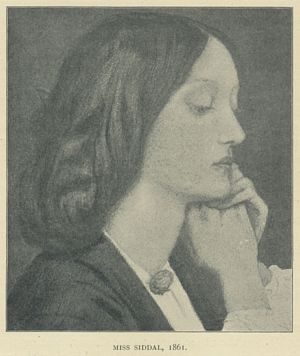

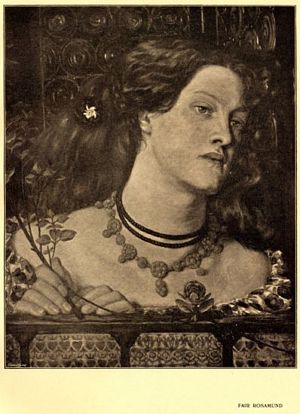

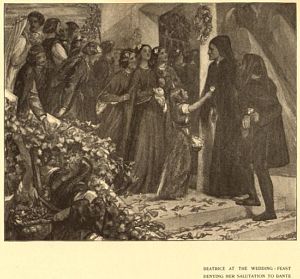

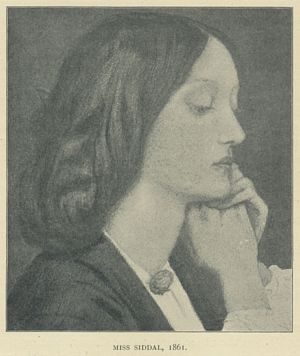

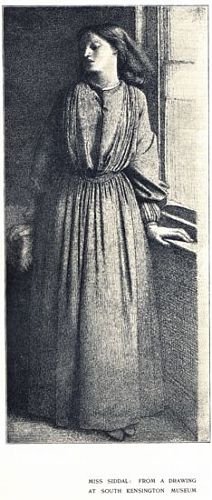

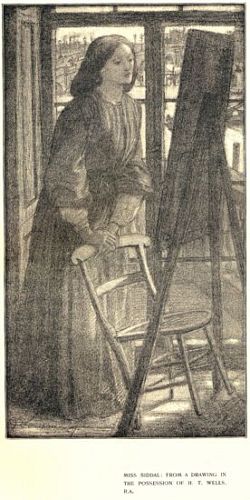

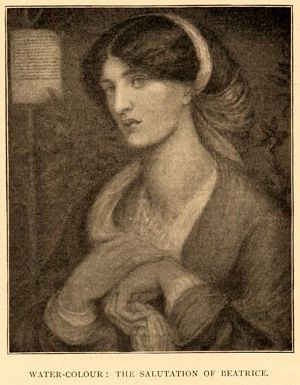

, and another drawing. Mr. Wells, R.A., has contributed two interesting

portraits of Miss Siddal

[portrait

1]

[portrait 2] and the water-colour

Beatrice denying the Salutation

—the companion drawing to which (in point of date and history),

viz.,

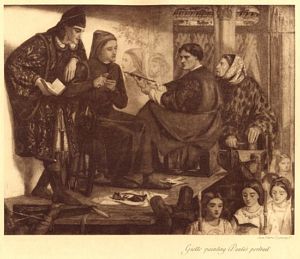

Giotto painting Dante's Portrait

, has been lent by its present owner, Mr. John Aird, M.P. Other owners

who have obligingly given me access to their pictures, and have in one or two

cases even sent them to London to be photographed, are Mr. W. R. Moss, Mr. S.

Pepys Cockerell, Mr. Francis Buxton, Mr. Charles Butler, Mrs. Jekyll, Lord

Battersea and Overstrand, Mr. William Imrie, Mrs. Clarence Fry, Mr. Trist, Mrs.

Coronio, Mr. Constantine Ionides, Mrs. A. Ionides, Sir Cuthbert Quilter, Prof.

C. E. Norton, Mr. T. H. Leathart, Mr. F. J. Tennant, Mr. Russell Rea, Mr. S. E.

Spring-Rice, Mr. A. T. Squarey, the Rev. S. A. Donaldson, Mr. William Dunlop,

Mr. Charles Ricketts, Dr. Spence Watson, Mr. Arthur Severn, Mr. Cosmo Monkhouse,

Mrs. Constance Churchill, the Hon. Percy Wyndham, Sir Henry Acland, Dr. H. A.

Munro, and the Corporation Art Galleries of Birmingham, Manchester, and

Liverpool. Mr. Rossetti has given me practically a free hand in the reproduction

of family portraits and drawings belonging to him, and has also allowed me to

use many of the negatives of pictures that were specially made for his brother,

sometimes before alterations of a disastrous kind had been undertaken. To Mr.

Frederick Hollyer, Mr. Caswall Smith, and the Autotype Company, I owe an

expression of thanks for generously giving me the use of many of their copyright

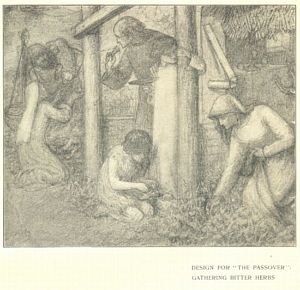

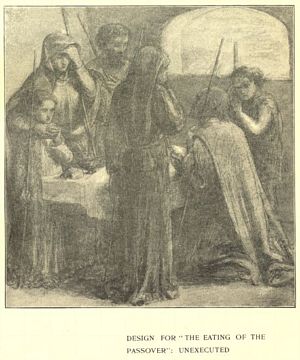

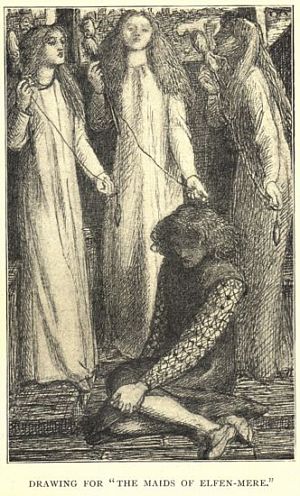

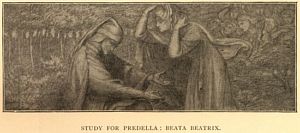

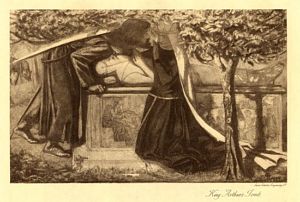

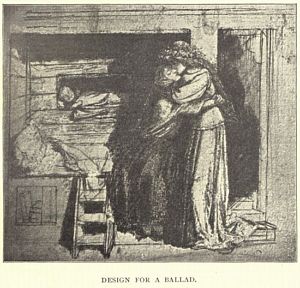

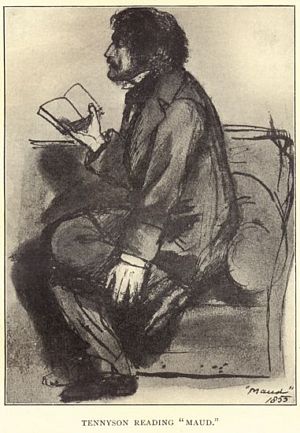

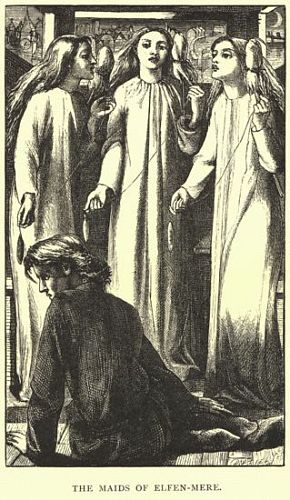

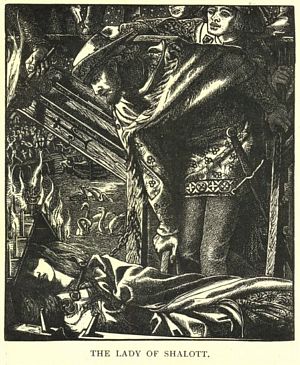

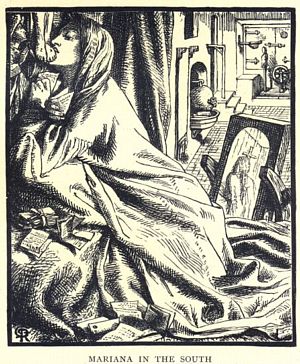

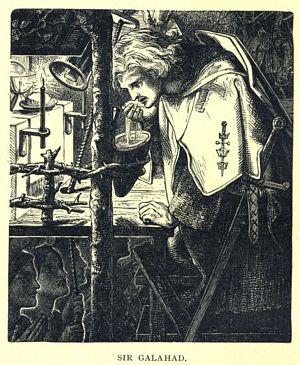

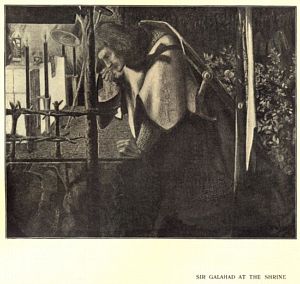

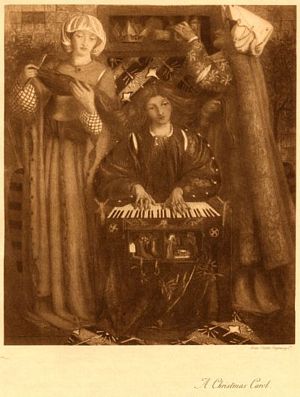

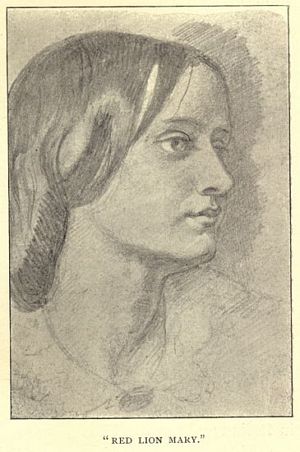

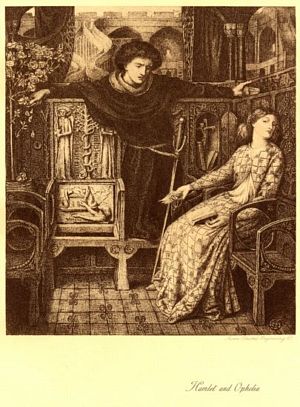

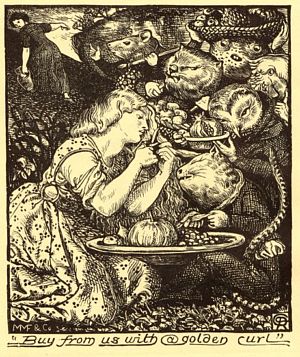

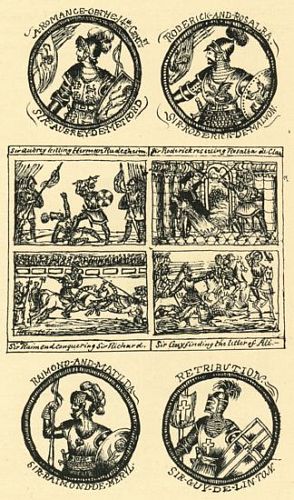

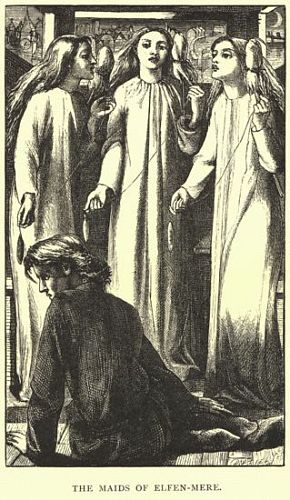

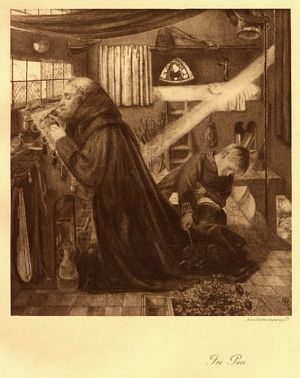

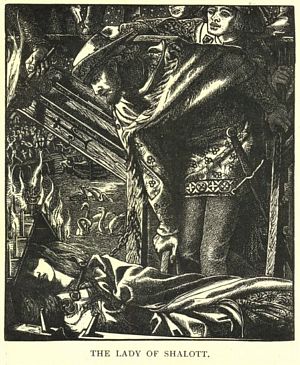

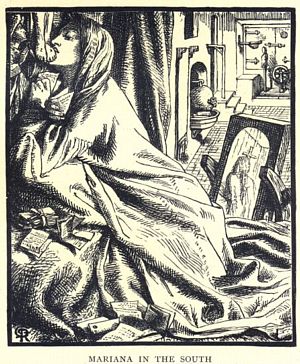

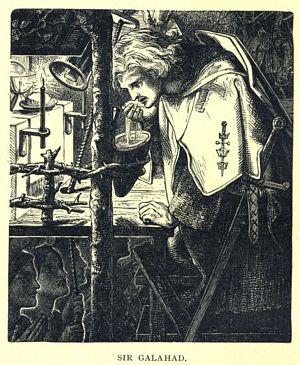

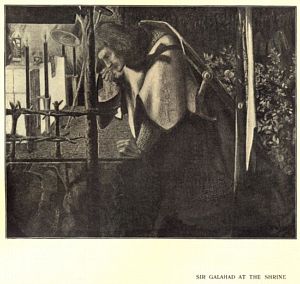

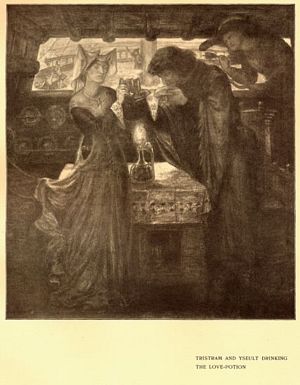

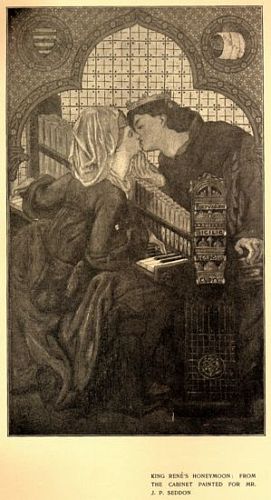

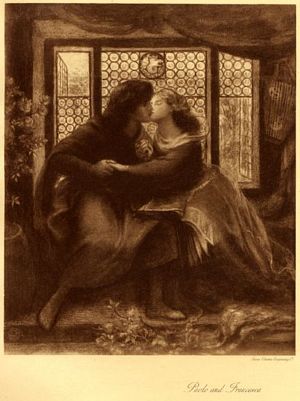

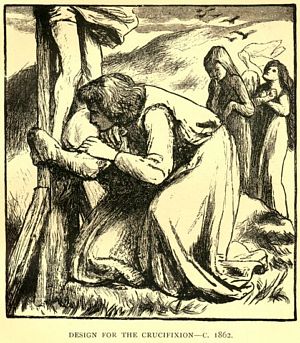

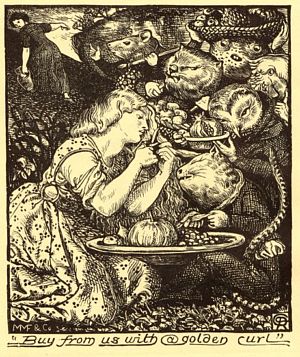

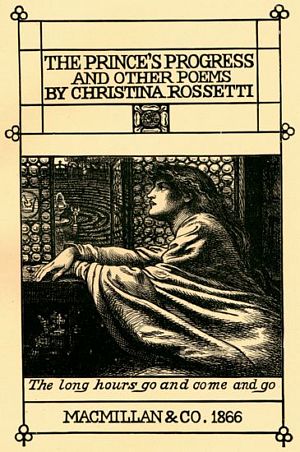

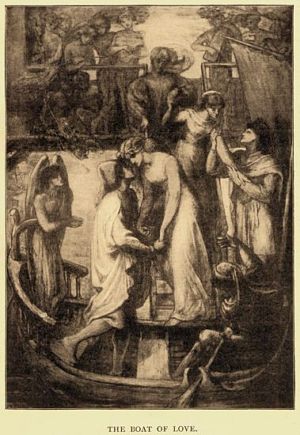

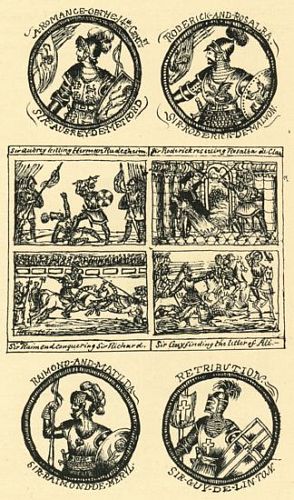

negatives, and to Messrs. Macmillan no less for the right to reproduce the five

wood-blocks

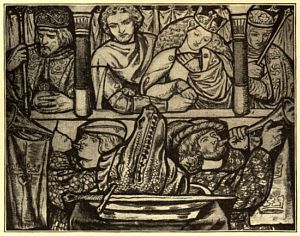

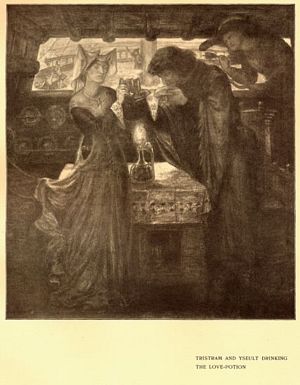

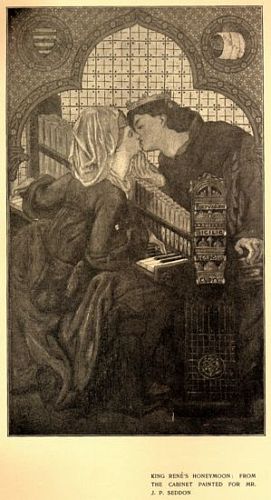

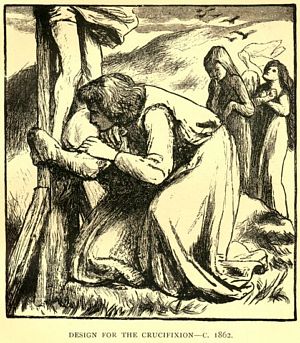

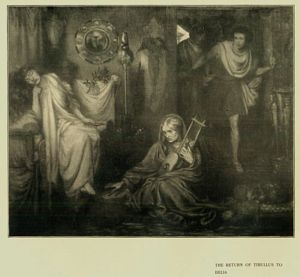

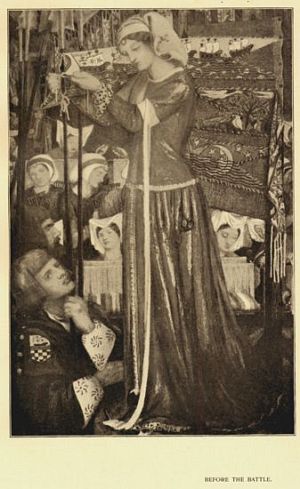

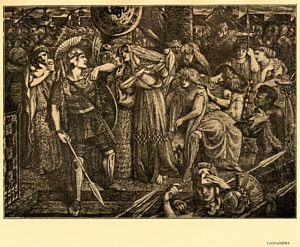

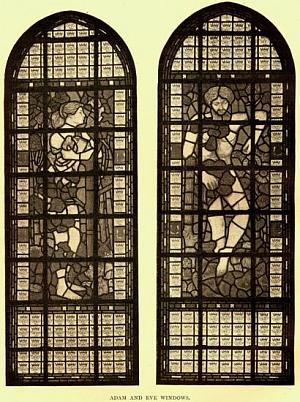

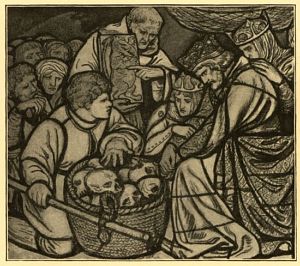

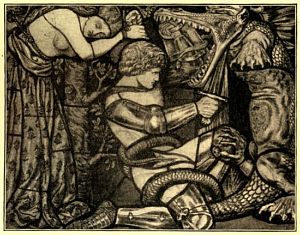

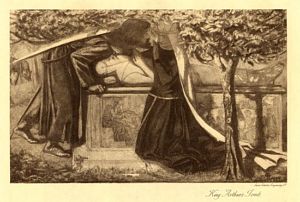

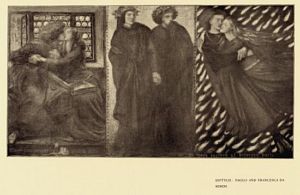

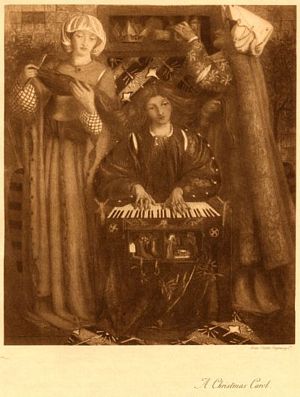

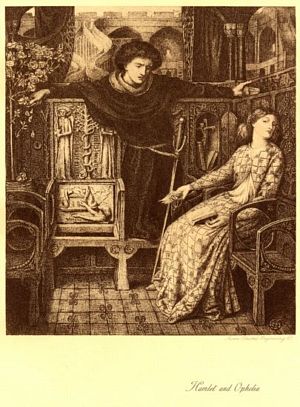

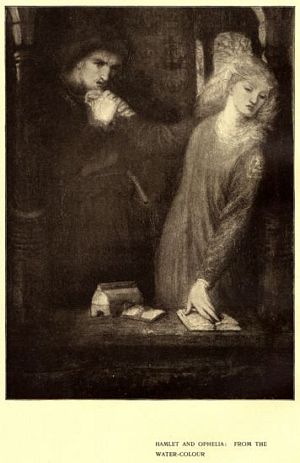

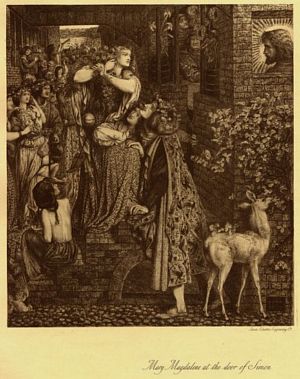

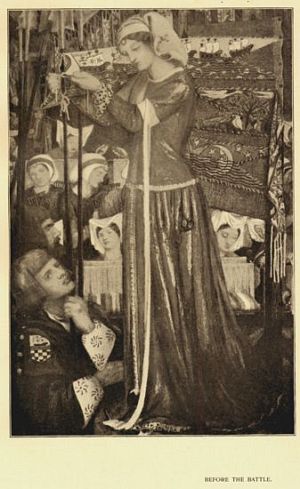

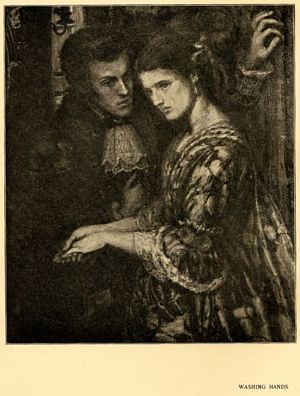

[block 1]

[block 2]

[block 3]

[block 4]

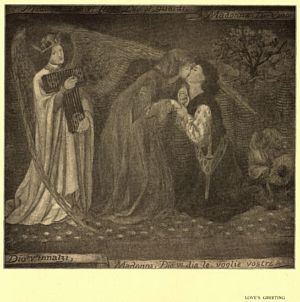

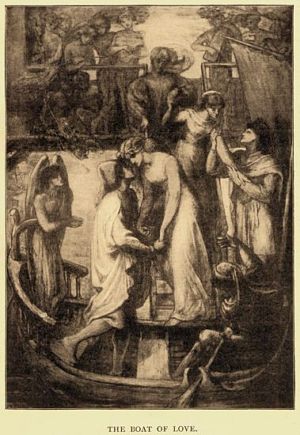

[block 5] done for Moxon's “Tennyson” and two others

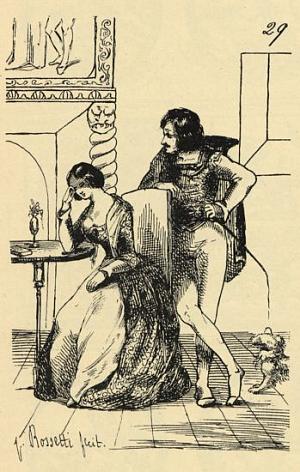

[plate 1]

[plate 2] from Miss Christina

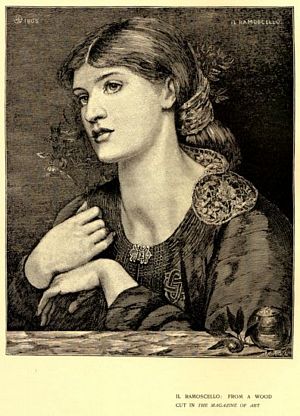

Rossetti's books. Messrs.

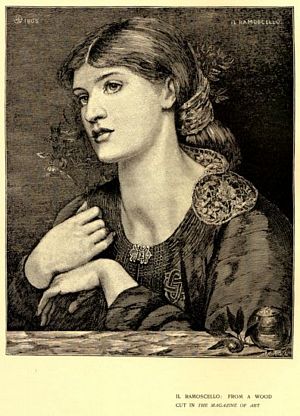

Sotheran, Mr. Duckworth, and the editor of the “Pall Mall Magazine” have kindly lent me various blocks or plates, and, finally, Messrs.

Cassell have my thanks for allowing two pictures to be reproduced from the

“Magazine of Art.”

With a few rare exceptions, owing to owners' refusals, or in the case of

The Blue Bower

and

The Blessed Damozel

from the pictures being held in trust, there is scarcely a work of

individual importance by Rossetti which will not be found illustrated in this

book or in some way represented. In general, moreover, where a choice existed,

it is the best version of each particular subject from which the reproduction

has been made, though there are cases where this was not possible, owing to the

pictures having gone abroad or become untraceable. It would hardly be believed

how difficult Rossetti's pictures are to find since their dispersal after the

great Graham, Leyland, Turner, Ruston, and Leathart sales. Even with the kind

help of Mr. Croal Thomson and Messrs. Agnew there are many that I have not

located, though I have been fortunate in borrowing private photographs of some

of these and published prints of others. No doubt the constantly increasing

value of Rossetti's works is partly responsible for their restlessness, but

there is something almost melancholy in the way that they seem perpetually to

change hands. The Rae and Heaton collections are almost the only ones of

importance that have remained intact. Mr. Ruskin, who at one time had quite a

number of good water-colours, has parted with all but the unfinished

Passover

, and no one seems to know where some of them have gone. The Boyce

collection has shared the same fate, though in this case the bulk of it has

passed into the hands of Mr. Murray, who amid the maelstrom of flux and change

has constituted himself a sort of natural vortex or harbour of refuge.

This is one of the circumstances which has made the illustration of a book on

Rossetti not altogether easy, and which may have prevented its being undertaken

before. Even now I am conscious of many omissions and failures, which mar the

completeness of the work. But it is no part of an author's duty to specify these

for his readers, most of whom will be ready enough to find them, and perfectly

candid in pointing them out.

H. C. M.

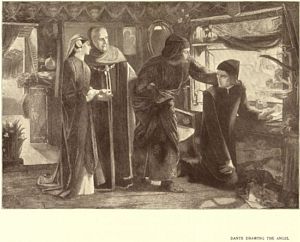

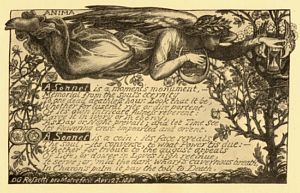

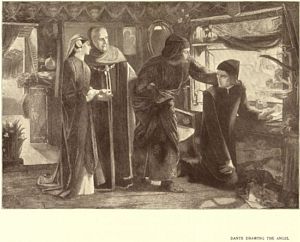

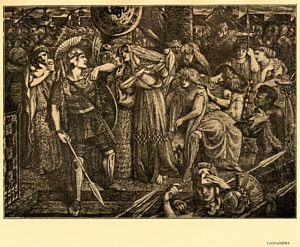

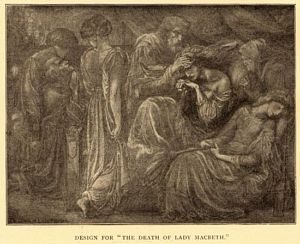

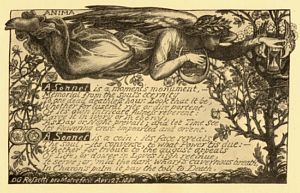

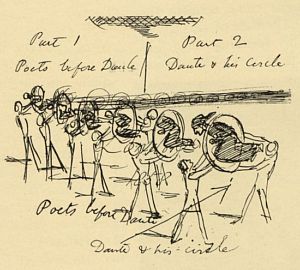

DESIGN FOR DANTIS AMOR, PAINTED BETWEEN THE DANTE AND BEATRICE PANELS,

1866.

See page 89.

Figure: Pencil. Inscribed at top: "IX JVN: MCCXC." Inscribed at bottom:

"QUOMODO SEDET SOLA CIVITAS." Oblong outline, framing the shape of the

angels' wings and coming to a point above his head and beneath his feet.

An angel, "Love," stands holding a clock and a down-turned

torch.

[

The Reproductions are the Work of the Swan Electric Engraving

Company

.]

DANTE GABRIEL, or, to give him his full christening name,

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti, was born on May 12th, 1828, at No. 38, Charlotte

Street, Portland Place, and was the second of four children, all born in

successive years. His

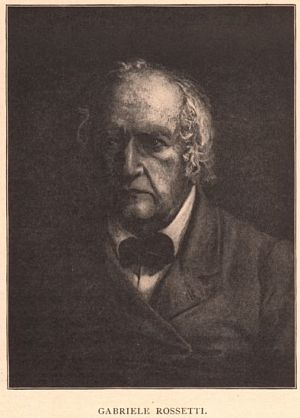

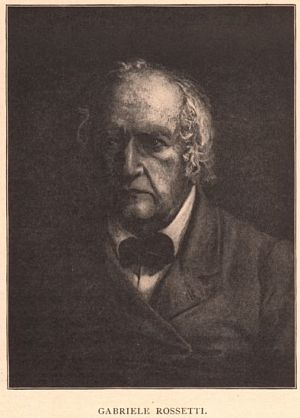

Gabriele Rossetti

Figure: Oil painting. Head and shoulders portrait of Gabriele Rossetti with

his head turned slightly to his right.

parentage and family life have been so copiously dealt with already in

the “

Memoir” compiled by his brother, Mr. William Michael Rossetti, that there is no

need here to do more than recapitulate the main facts. Gabriele Rossetti, the

father of Dante Gabriel, was a native of the city of Vasto, in the province of

Abruzzi, on the Adriatic coast of what was once the kingdom of Naples. He was a

man of superior literary ability and force of character, at one time custodian

of bronzes at the Naples Museum, who made himself obnoxious to the Bourbon King

Ferdinand during the suppression of the constitution in 1821, and was in

consequence proscribed and obliged to fly for safety. Assisted by a British

man-of-war in escaping to Malta, Gabriele Rossetti remained there for some time,

practising as an instructor in his native

language, until further annoyance drove him in 1824 to England. Here he settled,

and some years later obtained an appointment as Professor of Italian at King's

College. Meantime, in 1826, he had married a daughter of Gaetano Polidori, for

some while secretary to the notable Count Alfieri, and father also of that

strange being, Dr. John Polidori, who travelled with Byron as his physician, and

committed suicide in 1821. Gaetano Polidori's wife, Rossetti's grandmother, was

an Englishwoman, whose maiden name was Pierce. To his parentage the young Dante

Gabriel was indebted for much, but especially to his

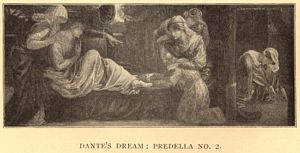

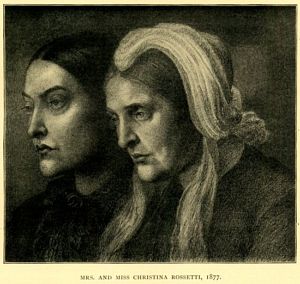

Mrs. Rossetti.

Figure: Chalk and pencil. Inscribed lower left: "Feb/62." Drawing of head

and shoulders, nearly in profile to right, wearing a white pleated muslin

bonnet; on either side a streamer falls forward over the

shoulders.Surtees, 187

mother. One can judge to this day of the latter's quiet sensible

character, and deep religious instincts, from the portraits left us by her son,

of which one is

reproduced here as typical. But,

besides these qualities, she possessed good literary and artistic judgment,

shrewd knowledge of human nature, and a fund of common sense which must have

effectually prevented the somewhat mystical spirit pervading the thoughts of her

young family from deteriorating into morbid and unhealthy channels. Between D.

G. Rossetti and his mother the warmest and most affectionate relations

prevailed, relations that were only severed by the former's untimely death on

April 9th, 1882. Mrs. Rossetti survived her son exactly four years

to the very day. Her husband

had died in April, 1854, honoured as a patriot in his native land with a

memorial statue

1 and a medal commemorating his

services. Their elder daughter, Maria, departed this life in 1876,

and in December, 1894, Christina Rossetti also died, leaving as sole survivor of

this brilliant family the younger son, William Michael, well known as a writer

of critiques on art and as the biographer of his more famous brother.

Albeit English in its main external features, the environment of the Rossetti

family in London remained essentially Italian during the lifetime of Gabriele

Rossetti. Their house was the resort of all classes of Italians passing through

or resident in town. Musicians and literary men met there with revolutionaries

fresh from the wasting struggle for Italian liberty. A romantic odour of

assassination hung round one at least of the regular habitués of the house, and

added spice to the somewhat fusty atmosphere of the father's own particular

studies. Gabriele Rossetti was a commentator on Dante, and himself a writer of

verse, mainly in a politico-satirical vein. He had a gift for declamation and

improvization, which is not so uncommon in men of his nationality as of ours;

but the exposition of Dante was his chief occupation, as well as the one by

which he is now best known. To the ears of the young Gabriel, familiarized by

habit with the sonorous metres of the “Inferno” and “Paradiso,” the name of Dante for many years conjured up no very stimulating

thoughts. It was not until he had begun himself in early life to read upon his

own lines, that the pictorial richness and splendour of the Florentine dawned on

him and seized him with its spell. There is a sketch by Rossetti of his father,

engaged upon his labours of interpretation, and surrounded, as Mr. W. M.

Rossetti has described him, by heavy folios in italic type, his “libri mistici,” full of the lore of Swedenborg,

alchemy, and Brahminism, with the aid of which he is devotedly burying the

poetry of his subject beneath unprofitable layers of teleological symbolism.

“The ‘Convito,’ ” says his son, “was always a name of dread to us,

as being the very essence of arid unreadableness,” an interesting

fact to remember when dealing, as we shall presently have to do, with the

influence which Dante was destined afterwards to exert upon two members at least

of the family.

Before passing to the early life of Gabriel Rossetti, a pair of independent

descriptions of the household and surroundings of No. 50, Charlotte Street,

whither the family removed from No. 38 in

Transcribed Footnote (page 3):

1The statue, I understand, has not yet been erected,

but is still in contemplation.

1836, may not be without interest, though to

some they will not be new.

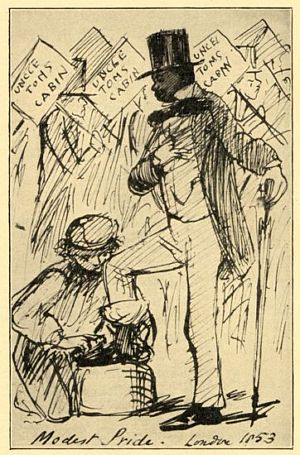

Mr. William Bell Scott, in his “Autobiographical Notes,” says, “I entered the small front parlour or dining-room of the

house, and found an old gentleman sitting by the fire in a great chair, the

table drawn close to his chair, with a thick MS. book open before him, and

the largest snuff-box I ever saw beside it conveniently open. He had a black

cap on his head furnished with a great peak or shade for the eyes, so that I

only saw his face partially.” This description tallies in a

remarkable way with the

drawing of his

father

just mentioned, done by Dante Gabriel in 1853, though

otherwise not remarkable for insight or fullness of detail. A more interesting

picture is one by Mr. F. G. Stephens, Rossetti's early associate, quoted from

his “

Portfolio” monograph:

“As might be expected of one possessing so many accomplishments, and

whose career was marked by so much courage, the professor was a man of

striking character and aspect. . . . To a youngster, such as I was, he

seemed much older than his years, and while seated reading at a table

with two candles behind him, and, because his sight was failing, with a

wide shade over his eyes, he looked a very Rembrandt come to life. . . .

Near his side, but beyond the radiant circle of the candles,—her erect,

comely, and very English form and face remarkable for its noble and

beautiful matronhood, sat Mrs. Rossetti, the mother of Dante Gabriel. He

too, leaning his elbows upon the table and holding his face between both

hands so that the long curling masses of his dark brown hair fell

forward, sat on the other side, his attenuated features outlined by the

candle's light.”

Reared in this studious atmosphere, it is not to be wondered at that the young

Rossettis early took to literature. Before they were six years old they had made

acquaintance with Shakespeare and Scott, in addition to the usual works of

childhood, and were steeped in romance of a more lofty kind than is common at

such an age. A healthy crudity of taste and strong boyish proclivities, together

with the influence of his mother, prevented this precocity from developing into

priggishness in the case of the youthful Gabriel, whose letters, even up to his

sixteenth or seventeenth year, are as remarkable for naïve simplicity as for

their rather florid style and sonorous diction. They are also marked by an early

sense of humour. How many children of fourteen are there who possess the power

of expression, to say nothing of the critical observation, shown by this

juvenile specimen of Gabriel's domestic correspondence.

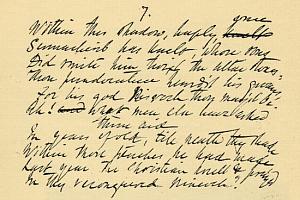

“CHALFONT ST.-GILES,

“

Thursday, 1

Sept.,

1842.

“MY DEAR MAMMA,

“We arrived safely at Chalfront at 12 o'clock yesterday. The village is

larger than I expected. The first thing we did on our arrival was to

demolish bread and butter, of which I at least was much in want. We then,

with considerable difficulty, opened Uncle Henry's trunks, and after

depositing a portion of their contents in a chest of drawers, sallied forth

to reconnoitre. I saw Milton's house, which is

unquestionably the ugliest and dirtiest building in the whole

village.

1 It is now occupied by a tailor. . .

.

“Yesterday I commenced reading ‘The Infidel's Doom,’ by Dr. Birch, which work forms part and parcel of Uncle Henry's

library. However, I have abandoned the task in despair. I then began ‘ The Castle of Otranto,’ which shared the same fate, and am now engaged on Defoe's ‘ History of the Plague.’ This morning we deposited Uncle Henry's books in a closet in Uncle

Henry's bedroom, which, in common with all the other closets in this house,

possesses a lock but no key.

“I do not think that I shall go to church on Sunday, for in the first place I

do not know where I can sit, and in the second place I find we are so stared

at wherever we go that I do not much relish the idea of sitting for two

hours the loadstone of attraction in the very centre of the aborigines, on

whose minds curiosity seems to have taken strong hold. . . . I ‘in

longing expectation wait’ the appearance of my dinner; for

which, however, I need not yet look, since it is now nearly three o'clock,

which is the nominal dinner hour, but, the fire having gone out, Uncle Henry

prophesies that it will not come till 4.

“I remain, dear Mamma,

“Your affectionate son,

“GABRIEL ROSSETTI”

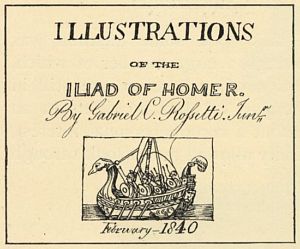

Of Rossetti's early literary efforts it is sufficient to mention two: “

The Slave,” a bombastic drama in blank verse, which occupied his faculties at the

age of five, and is chiefly remarkable in that connection (though the

correctness of spelling and versification is extraordinary), and “

Sir Hugh the Heron”, a legendary poem

Transcribed Footnote (page 5):

1For the credit of Chalfont it may be mentioned that

Milton's house has, since the date of this letter, been acquired for the

nation and put in proper order.

founded on a tale by Allan Cunningham. The

latter, a more ambitious effort, written when he was twelve, was privately

printed by his grandfather, Gaetano Polidori, and a copy exists in the British

Museum. This fact was in after years rather a source of dread to Rossetti, who

feared that some meticulous compiler might light upon the curiosity and include

it in his published works, as to which he was morbidly scrupulous. These two

productions do not sum up the juvenile work of Rossetti, of which a record has

been kept, but they are quite as much as it is fair to mention, and serve

sufficiently to show the romantic drift of his earliest ideas. In art he was scarcely less precocious, a pretty story

being told of a milkman, who came upon him in the passage sketching his

rocking-horse, and who testified his surprise at having seen “a baby

making a picture.”Drawings of this date exist,

and also later ones done when he was in the habit of preparing illustrations

for books he read and for his own romances.

1 In point of quality, however, these juvenile sketches are not to be

compared with those of many masters of the brush who began early, for example

with those of Millais, a veritable infant prodigy, and are chiefly interesting

in connection with a statement of his brother that “he could not remember

any date at which it was not an understood thing in the family that Gabriel

was to be a painter.”

In 1837, after a short preliminary training at a private school, Dante Gabriel

and his brother were admitted to King's College, where their father was Italian

professor. Here the former remained for four or five years, acquiring a fair

knowledge of Latin and French, with a smattering of Greek. German he learnt just

well enough to enter upon a study of the wonderful literature of that language,

and Italian, of course, came naturally to him. The drawing-master at King's

College was the celebrated Cotman, of Norwich, from whom, however, he derived

little or no instruction.His artistic training did not begin

until 1842, when he left school,

2 and entered himself at

a drawing academy known in those days as “Sass's,” and kept

by Mr. F. S. Cary, son of the translator of Dante.

As a schoolboy, Dante Gabriel is described by those who knew him as a boy of

gentle and affectionate nature, but singularly masterful as well. He himself

confessed to recollections of a want of hardihood and a dislike for active games

and exercise. The

Transcribed Footnote (page 6):

1Several of these relics of his childish days will

be found reproduced in a

supplementary

chapter

at the end of the book.

Transcribed Footnote (page 6):

2This is the date usually given. Mr. W. M. Rossetti

now thinks it should be 1841.

latter defect haunted him through life. He took

little exercise at any time but walking, and suffered in consequence, as he was

prone to admit, from some of the physical and mental disadvantages attendant

upon a sedentary habit.

To return to his artistic life, Gabriel Rossetti remained some four years at

Cary's Academy, during which period he seems to have acquired the bare rudiments

of his art and to have made a small reputation for eccentricity. In July, 1846,

having sent in the requisite probation-drawings, he was admitted to the Antique

School of the Royal Academy. His first appearance is thus graphically delineated

by a fellow-student, whose observant eye has preserved for us a probably

accurate conception of the fiery young enthusiast, impatient of ordinary

considerations in the matter of attire, burning with zeal to paint his already

vivid imaginings, yet scornful of the routine and drudgery by which it was

supposed that masterhood must be acquired. The description, from which the

following is an extract, has often been quoted before.

“Thick, beautiful, and closely-curled masses of rich brown

much-neglected hair fell about an ample brow, and almost to the wearer's

shoulders; strong eyebrows marked with their dark shadows a pair of

rather sunken eyes, in which a sort of fire, instinct with what may be

called proud cynicism, burned with a furtive sort of energy. His rather

high cheekbones were the more observable because his cheeks were

roseless and hollow enough to indicate the waste of life and midnight

oil to which the youth was addicted. Close shaving left bare his very

full, not to say sensuous lips, and square-cut masculine chin. Rather

below the middle height, and with a slightly rolling gait, Rossetti came

forward among his fellows with a jerky step, tossed the falling hair

back from his face, and, having both hands in his pockets, faced the

student world with an

insouciant air which savoured of thorough self-reliance. A bare throat,

a falling, ill-kept collar, boots not over familiar with brushes, black

and well-worn habiliments, including not the ordinary jacket of the

period, but a loose dress-coat which had once been new—these were the

outward and visible signs of a mood which cared even less for

appearances than the art-student of those days was accustomed to care,

which undoubtedly was little enough.”

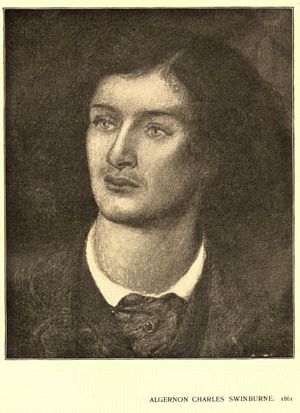

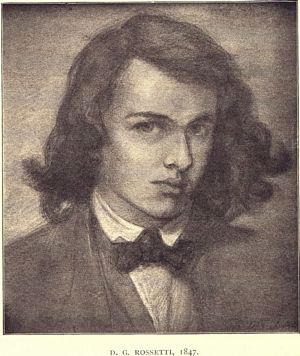

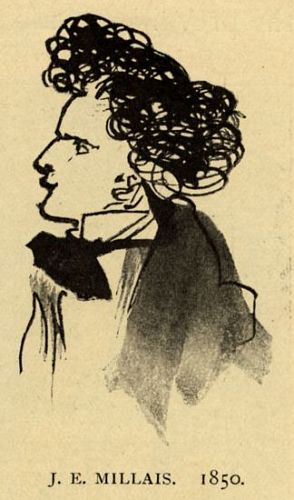

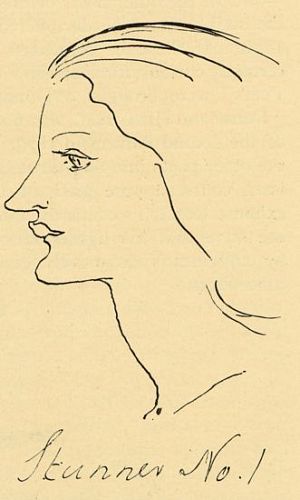

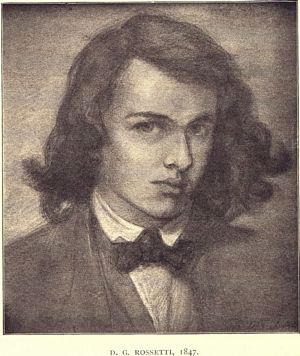

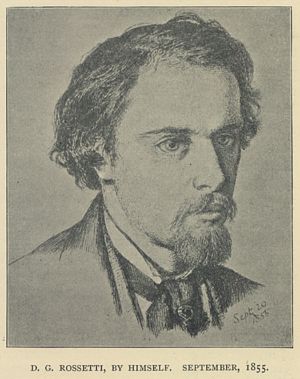

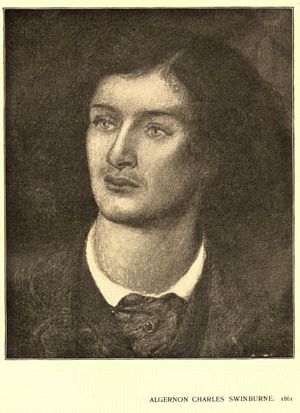

The clustering masses of hair are shown in the pencil sketch now at the National

Portrait Gallery, drawn by himself at the age of nineteen, and

reproduced here. The whole description is well

borne out by Mr. Holman Hunt, in an independent

description of Rossetti at about the same date, from which we get the additional

particulars that he was of “decidedly foreign aspect;” that he had staring,

dreamy eyes, and an aquiline but delicate nose, with a strongly marked

depression at the frontal sinus; and that his singularity of gait depended upon

the width of hip, which was unusual for a man. Mr. Holman Hunt also dwells upon

Rossetti's loud voice and rather blustering manner, which seem at first to have

jarred upon his retiring

D.G. Rossetti, 1847.

Figure: Chalk and pencil drawing of head and shoulders. A young D.G.R. with

long curling hair faces forward, with his head turned slightly to his

left.

disposition. He adds, however, that “anyone who has addressed him was

struck with a sudden surprise to find his critical impressions dissipated; for

his language was refined and polished, and he proved to be courteous, gentle,

and winsome, generous in compliment, and in every respect, so far as could be

shown by manner, a cultivated gentleman.” Those who have read Mr. Hunt's

affecting account of his own early struggles in the pursuit of art, and realized

the picture of himself there given, will easily perceive that there could have

been but slight affinity at first, as far as externals were concerned, between

himself and the buoyant Rossetti, bursting with animal spirits,

and carried away by the power of fascination and mastery which he exerted over

all who came into contact with him.

As a student in the dry atmosphere of the Academy Antique School Rossetti proved

a failure, and never passed to the higher grades of the Life and Painting

classes. Conventional methods of study were distasteful to him, and the

traditions of the Academy were especially arid and cramping to the imagination.

It will be necessary later on to give some description of the state into which

the art of painting had fallen in England before the fresh minds of the young

and romantic school, breaking away under Rossetti's leadership, caused such a

turmoil and revolution; but in the meantime, at the period we are dealing with,

it is probably correct to say that Rossetti grew tired of, rather than

disapproved of, the teaching in the school, that he was full of ideas craving

utterance on canvas, and that he wanted to paint before he could properly draw.

This impatience caused him to take a momentous and curious step, which certainly

entailed harm to him as a technical executant, though it may indirectly have

furthered his career as an artist. He decided to throw up the Academy training,

and wrote to a painter of whom not many people at that date had heard, but whose

work he himself admired, asking to be admitted into his studio as a pupil. This

was Ford Madox Brown, and for his own particular needs and line of thought

Rossetti could have lighted upon no man more absolutely suitable. Madox Brown

was only seven years Rossetti's senior, but he had studied abroad at Ghent,

Antwerp, Paris, and Rome, and had exhibited during the early forties some fine

cartoon designs for the decoration of the new House of Lords, which—especially

the well-known one of

Harold's body brought before William the Conqueror

—Rossetti had marked out from the rest of the competitive drawings when

they were shown to the public in Westminster Hall. The pictures by Brown which

Rossetti had seen, and which he mentioned in writing, were the

Giaour's Confession

, exhibited at the Academy in 1841,

Parisina

(1845),

Our Lady of Saturday Night

, and

Mary Queen of Scots

, of which he remarked “if ever I do anything in art, it will

certainly be attributable to a constant study of that work”. This,

and other rather florid compliments of the same sort, may well have impressed

Madox Brown, who was not accustomed to be complimented, with a shrewd idea that

he was being made fun of; and the story has been told how, in a suspicious frame

of mind, he armed himself with a stick and went forth to seek his unknown

correspondent. On arriving at the house he

was partly reassured by a door-plate; and the evident sincerity and enthusiasm

of the boy himself, when they met, overcame his generous warm-heartedness, and

made him agree to take Rossetti into his studio, and to teach him painting, not

for a fee, which he declined, but for the sheer pleasure of encountering and

training up a sympathetic spirit. So in March 1848, less than two years after

his admission to the Antique School, and with a clear two years more ahead of

him before he could possibly hope to learn painting by the ordinary course,

Rossetti quitted his

sicca nutrix, the Academy, and installed himself under Madox Brown's guidance at

his studio not very far from the paternal roof in Charlotte Street.

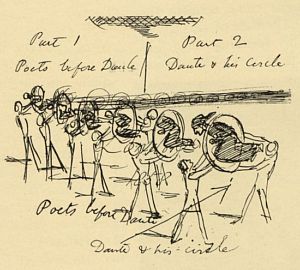

Before following his fortunes further in this direction we must go back over the

ground just traversed and note what Rossetti's activities in literature had

amounted to during the same period. These are no less than astonishing. To take

the greatest first, they include the bulk of the series of verse translations

from the early Italian poets, first published in 1861, and afterwards

republished under the altered title of “

Dante and his Circle.” Although worked on and revised from time to time, these translations

remain in all essentials much as Rossetti compiled them between the years 1845

and 1849, and they rank among the very finest work of the kind in the English

language, being no less remarkable for their high poetic qualities than for the

subtle dexterity of phrase by which the sound and sense of the originals have

been transplanted into a naturally colder tongue. Swinburne, most generous as

well as most far-sighted of critics, has expended himself in admiration of these

essays in an art in which he himself is so eminent; and they were mostly done by

a boy not out of his teens, thrown off in the intervals of a more absorbing

occupation, the study of painting. Rossetti's

translation of the “Vita Nuova” alone might stand as a monument of industry in such a case,

for it breathes a new spirit of language, a voluptuous and exotic style such as

has never been excelled for conveying the emotional mysticism and introspective

sentiment of a southern lover; but to this he added that great mass of verse

translations and sonnets, involving many days and many hours previously spent

over musty volumes at the British Museum in search of Italian poets. Even this

was not all, for between the same years he began a

translation in verse of the Nibelungenlied, the strong passion of which seized hold of him much as it seized hold

upon Wagner, and finished a

translation of Hartmann von

Aue's“Arme

Heinrich”

, which has been

thought worthy of a place amongst his

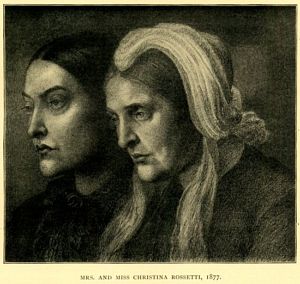

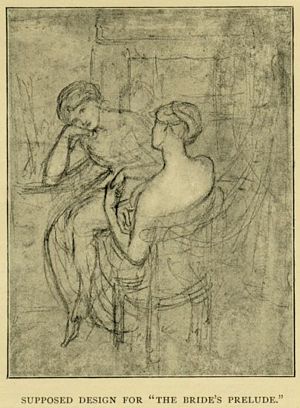

collected works. Besides these, in 1847, before he was nineteen years old, he

had written his best-known poem,

“The Blessed Damozel”, together with several others, including

“My Sister's Sleep”,

“The Portrait”, and considerable portions of

“Ave”,

“A Last Confession”, and the

“Bride's Prelude”. The performance of these literary efforts is so finished, the sentiment

so profound and mature, that one can hardly understand the ambition which kept

painting in the foremost place and made poetry the

parergon. The ease with which versification came to Rossetti may have blinded him

at first to the merits of his work in this art, as happened later in the case of

William Morris; but that he was not altogether ignorant of its value is shown by

the fact that when he was most in despair over his future he wrote to Leigh Hunt

asking for advice on the question of taking up literature as his profession and

inclosing some of his early poems. Leigh Hunt's reply is extant, and contains a

warm and evidently spontaneous eulogy of Rossetti's poetry, especially of its

thoughtful and imaginative qualities; but, it goes on to say,

“I need not tell you that poetry, even the very best—nay, the best in

this respect is apt to be the worst—is not a thing for a man to live upon

while he is in the flesh, however immortal it may render him in

spirit.” An inquiry made a little earlier into the prospects of

railway telegraphy (!) had proved hardly more promising, though very interesting

to record. Rossetti, therefore, was not encouraged to abandon painting as a

means of livelihood, and having made the arrangement already described with

Madox Brown, settled down with a characteristic mixture of enthusiasm and

despair to the pursuit of art. Brown at this time was engaged upon his

well-known picture of

Wiclif and John of Gaunt

. He was too conscientious a painter himself to suppose that anyone could

acquire the power of painting without previous drudgery, and shattered any hopes

that Rossetti might have cherished in this direction by coupling his permission

to copy a picture with insistence on a study of still-life,—tradition says a row

of pickle bottles.

Much as he owed to him in the way of instruction and sympathetic encouragement,

Rossetti did not remain long in Brown's studio, at all events as a regular

attendant, but left him after a few months to share a studio with Holman Hunt.

The beginning of this intimacy was curious and typical. On the opening day of

the Academy Exhibition (May 1848) Rossetti, says Mr.

Hunt,came up boisterously and in loud tongue made me feel very

confused by declaring that mine was the

best picture of the year. The fact that it was from Keats (the

picture was for

The Eve of St. Agnes) made him extra-enthusiastic, for I think no painter had ever

before painted from this wonderful poet, who then, it may scarcely be

credited, was little known. Rossetti begged to be allowed to visit

Hunt, for at the Academy schools they had barely been acquainted, and some time

later called and poured out his trouble about the pickle jars. Hunt considered

them sound, in the circumstances, but suggested as a compromise that Rossetti

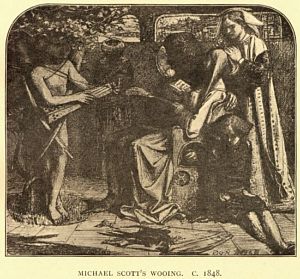

might try to paint one of his own designs, a subject recently contributed to a

sketching society,

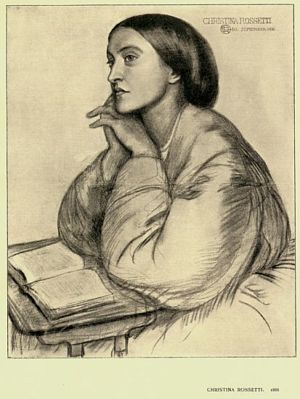

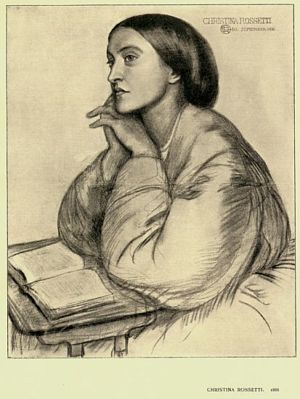

Christina Rossetti, 1852.

Figure: Pencil. Dated right: "Oct/52." 3/4 length oval drawing of Christina leaning her head on her right hand, seated in a chair reading

a book on her lap. The sleeves are flounced at the

elbows.Surtees, p. 184

and by way of practice might fill in all the still-life first. This

proposal was accepted at once, and so with apparent, but probably not actual,

fickleness Rossetti once more shifted his ground, and agreed to work for a time

with Hunt, sharing for this purpose a studio which the latter had just taken in

Cleveland Street, Fitzroy Square. Here (as well as later in a studio which he

took for himself at 83 Newman Street) Brown, whose staunch, unalterable

friendship continued to the end of Rossetti's life, visited him from time to

time, and gave him the benefit of his advice; and here, amid what Mr. Hunt has

described as the most dismal and dingy surroundings, Rossetti began to paint his

first picture. Up to this time he had done little beyond studies and sketches,

including a number of

portraits, some of which show excellent work.

The year 1848 marks his transition artistically from boyhood to adolescence, a

gracious adolescence adorned by many qualities that we too often look for in

vain in an age of tricky cleverness and pernicious skill; an adolescence in

which depth of feeling and height of aspiration transcended the power of

accomplishment, and no artificial or showy mannerisms obscured the honest

endeavour and deep-set seriousness of purpose that characterized, not him alone,

but the whole of the small band of workers with which he presently became

associated. The formation of this band, and the painting of Rossetti's first

picture, bring us to the story of the now famous Pre-Raphaelite movement, and

will more properly serve to begin a new, than to end a preliminary chapter.

IN relating afresh the history of the “Pre-Raphaelite” movement, one has many

precedents to choose from. According to the point of view selected one may see

in it the conscious expression of a great artistic revival, deliberately planned

by a body of zealots, and based upon a structure of lofty principles; or one may

go to the opposite extreme and regard it merely as an exuberant freak, an

irresponsible outburst on the part of a few impulsive youths linked together for

one brief moment by a mutual combination of enthusiasm and high spirits. For

both of these points of view ample authority might be quoted, and the truth as

usual lies somewhere safe between them. For the more emotional and serious

aspect of the case we have to thank Mr. Ruskin, who, finding in the work of the

men in question qualities and tentative aims such as he himself admired,

forthwith, as his manner was, read into it all the high morality of purpose and

principle that he conceived appropriate to ideal craftsmanship. On the other

hand, there have never lacked writers who from personal dislike, or, it may be,

a touch of jealousy, have tried to depreciate both Rossetti's work and his

wonderful influence over others. The facts of the case are, it happens,

abundantly in evidence. From Mr. Holman Hunt, Mr. F. G. Stephens, Mr. W. M.

Rossetti, and from others, who, if not so intimately connected with the movement

as these, were at all events in a good position to know about it, we have

received separate, and on the whole confirmatory accounts of its origin and

aims. No personal feeling or bias any longer obtrudes itself into the matter; we

can see the truth, if we will, in a clear perspective, and nothing remains to

obscure our vision but the amount of distortion that it may have contracted from

impressions formed on writers of the above-mentioned divergent opinions, or from

strongly developed artistic sympathies and prejudices.

The tendency has been on the whole, not unnaturally, to exaggerate the

significance, and to over-estimate the importance of the “Pre-Raphaelite

Brotherhood,” which after all was but the grain of mustard seed from which a

great tree sprung. Looking upon the tree, some are apt to magnify the seed,

forgetting what qualities of climate, soil, or accident may have assisted to

promote its growth. Those who do so, however, must either not have passed

through an impressionable youth themselves, or else have forgotten how naturally

at such a budding age men form romantic coteries based upon common friendships,

common ideals, and common habits of life. In such associations there is nearly

always one dominant personality which gives the tone to the set. A craving for

expression, and more particularly for expression in verse, is also a general

characteristic. The intellectual standing of the members of such a group is, no

doubt, a measure of the value of such expression, but not of its earnestness or

motive power, its romantic affinities, or its influence upon the men so brought

together. Dozens of “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoods” are formed every year, at the

great schools and at the universities, tracing lineal human descent from the

classical age which combined Platonic friendship with an enthusiasm for

philosophy. That few or none of them rise to celebrity is not so wonderful as

that one should have attained to

such celebrity. Accident and

circumstance, at least as much as the strong personal qualities of the members

of the group, combined to bring this about; and if argument were needed to prove

it, beyond the witness of the facts themselves, it would be found in the

deprecatory manner in which the leading “Pre-Raphaelites,” and none more than

Rossetti, were accustomed to look back on their turbulent, romantic, and on all

accounts most interesting past.

The formation of the “Brotherhood” came about in the following way. We have

noted the somewhat sudden alliance between Rossetti and Holman Hunt, and their

plan of sharing a studio to carry out work in common. Through Hunt, Rossetti had

become acquainted with Millais, and had joined, or helped to start, a

“Cyclographic Society,” numbering several members, to wit, Thomas Woolner, F. G.

Stephens, Walter Deverell, John Hancock the sculptor, James Collinson, William

Dennis, J. B. Keene, and some four or five besides. The scheme was for members

to contribute drawings to a portfolio which was sent round for all the rest to

criticise. Like other institutions based upon mutual candour, this society

enjoyed a very brief existence, and was mainly of service in weeding out those

who had no sympathy with the new ideas which

were ripening in Rossetti and his friends from those who had. The final

development of these ideas was brought about by a meeting in Millais's home in

Gower Street, where the three alighted upon a

volume

of engravings

after the frescoes in the Campo Santo at Pisa. Ruskin

has spoken scornfully of this work as “Lasinio's execrable

engravings,” but whatever their quality they at least served to show

that in the earlier men, who preceded Raphael, there was a feeling for earnest

work, a striving after lofty expression, which was worth more as an inspiration

than the rigidly mechanical fashion of painting stereotyped subjects which had

come into vogue in England. Why this mechanical cult should ever have become

grafted on to the ill-used name of Raphael, and shadowed by his stately fame, is

a difficult matter to explain, and requires an excursus into the history of

European art. Its effect on the teaching of the day, however, is summed up in

the following incisive passage by Ruskin:

“We begin, in all probability, by telling the youth of fifteen or sixteen

that Nature is full of faults, and that he is to improve her; but that

Raphael is perfection, and that the more he copies Raphael the better;

that after much copying of Raphael, he is to try what he can do himself

in a Raphaelesque, but yet original, manner: that is to say, he is to

try to do something very clever, all out of his own head, but yet this

clever something is to be properly subjected to Raphaelesque rules, is

to have a principal light occupying one-seventh of its space, and a

principal shadow occupying one-third of the same; that no two people's

heads in the picture are to be turned the same way, and that all the

personages represented are to have ideal beauty of the highest order,

which ideal beauty consists partly in a Greek outline of nose, partly in

proportions expressible in decimal fractions between the lips and chin;

but partly also in that degree of improvement which the youth of sixteen

is to bestow upon God's work in general.”

This canting and misdirected worship of Raphael by men who had discarded his

spirit, and the realization that before Raphael there were painters of lofty

aim, may well have determined the title under which the three enthusiasts

conspired to band themselves in revolt. From most points of view it was

unfortunate. It meant very little in actual fact, it was misleading so far as it

did mean anything, and it was responsible for much of the acrimony and abuse

which the devoted trio afterwards brought down upon their most meritorious

efforts. One curious feature

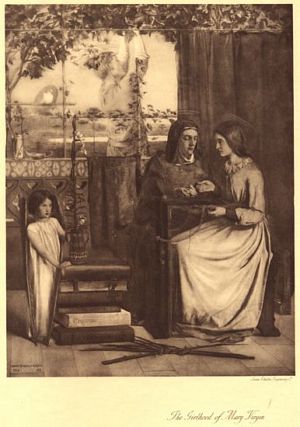

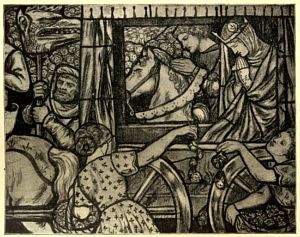

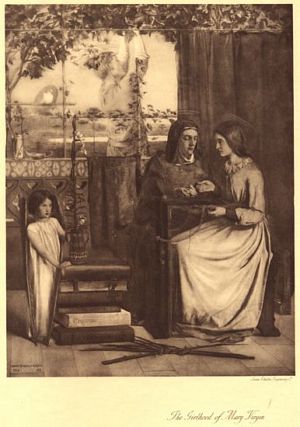

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin

Swan Electric Engraving C

o.

Figure: Oil. Signed and dated lower left corner: "Dante Gabriele Rossetti

P.R.B. 1849." The young Mary, facing to the left and seated in front of

her mother, St. Anne, embroiders a white lily on a piece of red cloth.

The lily she copies is placed a few feet away atop a pile of books, and

is held by a child angel. A trellis runs behind this scene, and behind

it St. Joachim reaches upward to prune a running vine. A Dove and the

lake of Galilee are behind him.

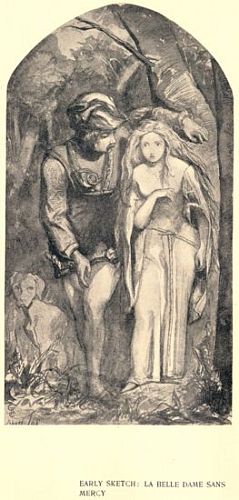

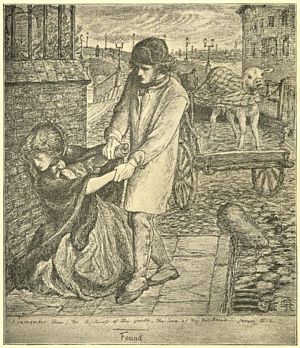

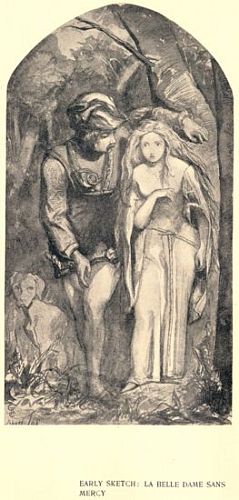

Early Sketch: La Belle Dame Sans Mercy

Figure: Pen and sepia with pencil, arched top. Monogram and date lower left

corner: "April/48." Two whole-length figures in a forest, facing to

front. The man stands on the left, looking at the girl while leaning his

left arm on the tree behind her. She looks to the front, with her long

hair unbound. A dog sits to the man's left.

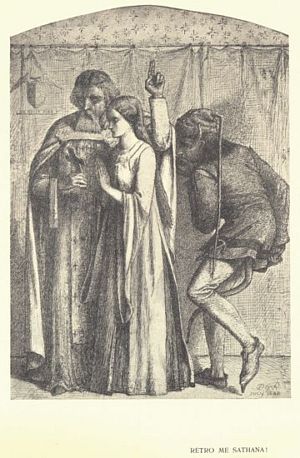

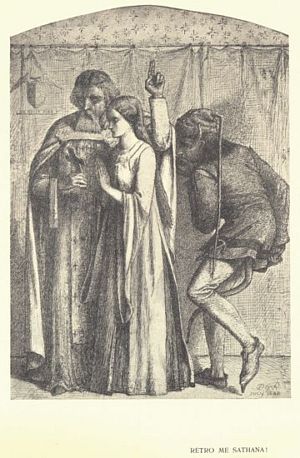

Retro Me Sathana!

Figure: Pen and ink, arched top. Inscription on shield: "Ex Nocte Dies."

Initialled and dated lower right corner: "July 1848." Three full-length

figures before a curtain. On the left, a priest gazes at a cross held in

his right hand, raising his left hand in blessing above the head of a

young woman, who also gazes downward at the cross. A shadowy figure with

horns and a tail sneaks up behind them.

of the matter is that they appear to have possessed between them

at this time a comparatively slight acquaintance with pre-Raphaelite pictures,

not more, perhaps, than the average intelligent visitor to the National Gallery

to-day. Scarcely anywhere in their writings (we must except one article by Mr.

F. G. Stephens) do we find praise, or even mention, of most of the great

pre-Raphaelite painters. Nothing of Mantegna, Botticelli, Bellini, Orcagna, Fra

Angelico, Melozzo, Lippo Lippi, or Piero della Francesca. At a slightly later

date Rossetti visited Bruges, and fell in love with Memling; but his letters

even then reveal some very crude preferences in art. Whatever was perceived or

imagined in the work of the men they decided to follow must have been largely a

matter of instinct, backed up by a strong sympathy for the naïve and simple

charm of the few early Italian pictures which they had seen. Perhaps the fact

that Keats too praised the early painters had something to do with it, for Keats

was a beloved idol with all three, most of all with Rossetti, who had

rediscovered him on his own account when his poetry was practically dead. In

addition, a bond of sympathy may be traced in the fact that the ancient

pre-Raphaelites, like these new ones who took their name, had established a

revolt from the effete and degraded classicism into which Byzantine art had

lapsed. They too had had to seek out nature afresh, by the light of their own

genius, and to invent new laws and new styles as a protest against the

mechanical system enforced upon them. The precedent showed to our reformers a

golden age of painting, crowned with the names of glorious painters, not perhaps

held so glorious then as they are to-day, when many persons outside the ranks of

art have learnt to love their quaint simplicity and to draw from it the noblest

inspirations. It is a mistake to suppose that what Rossetti and his companions

admired or sought to imitate in these old masters was the mediæval and primitive

style of painting. The mediæval quality proved infectious, no doubt, and may

have influenced all more or less at first in the direction of angularity and

awkward composition. But there were other causes which also contributed to this.

Amongst them may be mentioned an idea that for every scene an actual unidealized

room or landscape must be painted, and the figures grouped without reference to

arrangement; as well as another that for each figure a definite model must be

taken and followed even to the extent of blemishes. This counsel of perfection,

if it was ever seriously accepted, was certainly not followed even from the

first; but the fact of its proposal shows the austere lines upon which these

youthful painters proceeded, and helps to

explain what many people have found a stumbling-block, the lack of grace and

harmony in some of their earliest compositions. What they sought to follow in

the old Italian models, however, with all their archaism and immaturity of

skill, was the honest striving after nature, sincerity of style, decorative

simplicity, and, by no means least, the pious selection of worthy subjects. It

is this last quality, exhibited alike by all the members of the Brotherhood,

that more plainly than anything marks the cleavage between their

“pre-Raphaelite” work and the commonplace painting of the day. They set

themselves to paint great and ennobling subjects, often greater than they could

achieve, out of their imagination, when the rest of the world (always excepting

men like Madox Brown, who belonged to them in spirit) were painting what Ruskin

calls “cattle-pieces,” and ‘sea-pieces,’ and ‘fruit-pieces,’ and ‘family

pieces;’ the eternal brown cows in ditches, and white sails in squalls, and

sliced lemons in saucers, and foolish faces in simpers.”

In the inauguration of the Brotherhood Rossetti took a specially

active part, and the title itself was invented by him. One would not be far

wrong in saying that the whole idea was his, and that the two companions who

share the honour of its conception were dragged, enthusiastically enough without

doubt, not for the first or last time at the glowing wheels of his fervid

chariot. “Rossetti,” says one of them—Mr. Hunt, of course, for Millais was

remarkably reticent about those early days—“Rossetti, with his spirit

alike subtle and fiery, was essentially a proselytiser, sometimes to an

almost absurd degree, but possessed, alike in his poetry and painting, with

an appreciation of beauty of the most intense quality.” Millais is

credited in the same sentence with a rare combination of artistic faculty and

British common sense. “He was,” says Mr. Hunt, “beyond

almost anyone with whom I have been acquainted, full of a generous quick

enthusiasm; a spirit on fire with eagerness to seize whatever he saw was

good, which shone in every line of his face, and made it, as Rossetti once

said, look sometimes like the face of an angel.” His whole

after-career shows how completely thisBrother was fascinated and

dominated at the time by the imaginative natures round him, and with what

wonderful results for art. Though younger than his companions in age, in

painting he was already their superior, and his brilliant reputation as a

student was invaluable in the hour of strife; but in imaginative and poetic

qualities he was, compared with Rossetti, deficient, and such poetic

charm as breathes from his early pictures,

and from an occasional later one like

The Vale of Rest

, is unquestionably owing in part to the influences under which he fell,

and to that “spirit on fire with eagerness to seize whatever he saw was

good.” Of the third member of the trio, the writer of the foregoing

appreciations, a fair impression can be got from the autobiographical sketch

which he contributed to the “Contemporary Review” (April, May, June, 1886), in which with almost anatomical minuteness he

lays bare the secrets of his early struggle to win a way betwixt art and

commerce, and his heroic sacrifices for the former. At the time of the formation

of theBrotherhood he was twenty-one years old, and practically

out of his studenthood, his style being already formed on the almost painfully

laborious lines from which it has never deviated. In the sense in which the

“Brotherhood” professed to be pre-Raphaelite,i.e., in adherence to nature and in choice of great subjects,

Holman Hunt was, if the phrase may be permitted, the most eminently

pre-Raphaelite of them all. And he has remained so. The long series of journeys

undertaken in the East for the purpose of acquiring the proper setting and the

true local colour for his scriptural subjects prove that to him at least the

profession of “seeking nature” in its extreme sense was a real one, and not a

passing whim begotten of youthful enthusiasm. Mr. Hunt says, nevertheless, that

the title of “Pre-Raphaelite” was adopted partly in a spirit of fun, and, like

other names which have acquired honour, was originally a term of reproach

invented by their enemies. On this account they prudently decided to keep it

secret, and to let no outward symbol of their union appear beyond the mystic

initials P.R.B., which were to be used on all their pictures and in private

intercourse.

The next step was to enroll sympathetic fellow-members. Besides the three

founders of the Brotherhood, four more or less active adherents were enlisted.

Holman Hunt introduced Mr. F. G. Stephens, who at that time was a painter, but

very soon abandoned art for criticism. Woolner, the afterwards well-known

sculptor, whose contributions to the movement were mainly poetical, was

introduced by Millais, or possibly Rossetti; and the latter certainly was

responsible for the remaining two recruits, his brother and James Collinson.

Collinson, a torpid member at the best, and elected apparently on the strength

of one picture which Rossetti thought “stunning,” was mainly

useful as a butt to the others, who used to make fun of his sleepy nature and

drag him all reluctant from his bed to go for midnight walks. Shortly

afterwards, being seized

with religious propensities, he vacated his

membership and retired to Stonyhurst. Several other intimates and associates

have at one time or another been credited with membership of the “P.R.B.,” but

erroneously, as the survivors declare. Two men who were much in sympathy with

the movement, one of them its more than putative father—Madox Brown and William

Bell Scott—might well have joined it; but the former disapproved of anything

resembling an artistic clique, and the latter had somewhat similar reasons for

not being personally associated with the organization.

For the doings of the Brotherhood, sane and otherwise; for their weekly

meetings; their code of rules; the serious way in which they regarded their

mission, and the jocular way in which they customarily discussed it: for these

and many other interesting details of its career, including the gradual decline

in enthusiasm for its maintenance as the individual qualities of the members

began to develop upon divergent lines, the curious reader will do well to

consult Mr. W. M. Rossetti's “

Memoir.” Mr. Rossetti, not being an artist, was himself elected secretary to

the Brotherhood, and with businesslike care he has preserved in a diary all the

daily and weekly occurrences that came under his notice. These have not yet been

published in a complete form; but no doubt they will be some day, and then there

will be nothing left to tell. Such particulars, however, do not properly come

within the scope of this record, interesting as they may be from a personal

point of view. It is sufficient to say that the weekly attendances of the

Brethren, at first a constant source of pleasure and mutual help, had become

very irregular by December, 1850, that an attempt was made to revive them in

January, 1851, but without effect, and that Millais's election to the Academy in

1853 gave a final quietus to the organization, which for some time previously

had ceased to exist save in name. The ranks of the Brotherhood had not even

remained intact. In addition to Collinson, it had lost Woolner, who went to

Australia when the emigration craze was at its height. To replace the former a

young painter, Walter Howell Deverell, had been nominated, but his election was

regarded by some as invalid. Deverell, whose painting of

Viola and the Duke in

Twelfth Night remains an almost solitary testimony to his genius, unhappily died

young. He possessed many graces of appearance and manner, and was in all

respects a fascinating personality. Behind the Brotherhood, and hitherto

unmentioned, we seem to catch a glimpse of another very gracious, but very

retiring figure, that of Rossetti's sister Christina, who in addition to her deeply

religious and poetic gifts possessed a quiet

fund of humour to be expended on the events that occurred within her little

circle. The decay of the “P.R.B.” is thus recorded by her in a sonnet of

appropriately irregular form.

- “The P.R.B. is in its decadence:

- For Woolner in Australia cooks his chops,

- And Hunt is yearning for the land of Cheops;

- D.G. Rossetti shuns the vulgar optic;

- While William M. Rossetti merely lops

- His B's in English disesteemed as Coptic.

- Calm Stephens in the twilight smokes his pipe,

- But long the dawning of his public day;

- And he at last the champion great Millais,

- Attaining Academic opulence,

- Winds up his signature with A.R.A.

- So rivers merge in the perpetual sea;

- So luscious fruit must fall when over-ripe,

- And so the consummated P.R.B.”

We left Rossetti, in order to describe the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite

Brotherhood, at the point where he had just settled down in a joint studio with

Holman Hunt to paint his first picture. In an enthusiasm for community of

action, and a spirit of devotion to Keats, it had been proposed that each of the

Brethren should illustrate, by an etching, a scene from that poet's “Isabella”. Hunt, however, was already engaged upon his picture of

Rienzi swearing Revenge over his Brother's Corpse

; Millais had work of a less than Pre-Raphaelite character to finish off,

and Rossetti himself was seized with desire to paint a subject which much

commended itself to his intensely mystical and symbol-loving mind,

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin

. The only one of the three, eventually, who touched Keats that year

(1848) was Millais, who achieved a real triumph with the striking picture,

Lorenzo and Isabella

. He had been engaged to the last minute upon his old work, when

suddenly, in the graphic words of Mr. Hunt, about November, the whole

atmosphere of his studio was changed, and the new white canvas was installed

on the easel. Day by day advanced, at a pace beyond all calculation, the

picture now known to the whole of England, which I venture to say is the

most wonderful painting that any youth still under twenty years of age ever

did in the world. Whether posterity will support so overwhelming a

verdict as this may, without disrespect either to the critic or the picture, be

questioned.

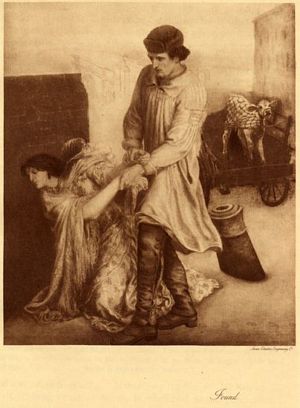

Rossetti's picture, as can well be imagined, gave him endless

trouble, and was a source of the most violent

fits of alternate depression and energy. During the painting of it his kindly

mentor, Brown, frequently visited the studio occupied by the pair of Brothers,

and assisted them impartially with advice and technical knowledge. At the same

time, Brown's diary, a document full of dry sardonic humour and quaint touches,

to say nothing for the moment of its pathos, contains many anecdotes of

Rossetti's exasperating changefulness and want of consideration, which show that

kindness did not blind the painter to his pupil's foibles. To Brown's

description of Rossetti, “lying, howling, on his belly in my

studio,” and, at another time, reduced by struggles with impossible

drapery to an almost maudlin condition of profanity, we may add Hunt's

description of how he had solemnly to take his companion out for a walk and

explain that if the interruptions of temper and multiplication of difficulties

did not cease, neither of them would have a picture finished to show alongside

of Millais's—a remonstrance which he says was effectual and taken in perfect

good part.

So by the following spring (1849) all three pictures were ready for exhibition,

and were hung, Millais's and Hunt's in the Academy, and Rossetti's either from

choice or necessity in the so-called Free Exhibition held in a gallery at Hyde

Park Corner. Here it was bought for £80 by the Marchioness of Bath, in whose

family an aunt of Rossetti's was acting as governess; and on her death it was

bequeathed to her daughter, Lady Louisa Feilding. It is now in the possession of

Mrs. Jekyll, one of the daughters of the late William Graham, by whose courtesy

it is reproduced here.

The picture has lately become well known by its re-exhibition at the New

Gallery, and is on many accounts a favourite one with lovers of Rossetti's work.

For delicacy and charm of sentiment there are few to be preferred to it, even

though the work, and especially the colouring, may not be in all respects of the

strongest. Considering the painter's age and want of proper training, it is a

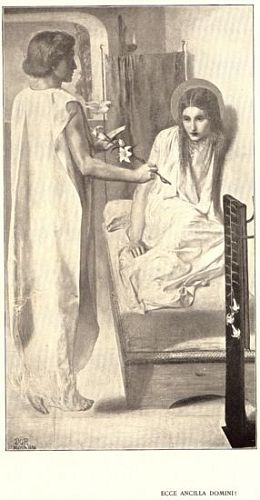

masterly performance. The scene shown is a room in the Virgin's home, with an

open carved balcony at which her father, St. Joachim, is tending a symbolically

fruitful vine. On the right of the picture, shown against an olive-green

curtain, are the figures of the Virgin and her mother, St. Anna, seated at an

embroidery frame. The latter, clothed in dark green and brown, with a nun-like

head-dress of dull red, sits watching with clasped hands the work before her,

whilst the young girl, a most untypical Madonna, in simple grey dress with pale

green at the wrists, pauses with the needle in her

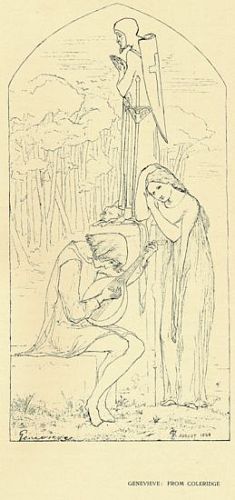

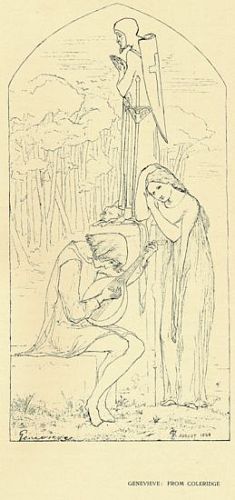

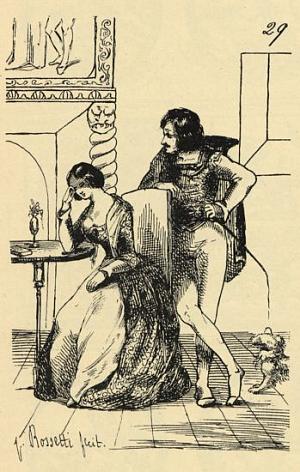

Genevieve: From Coleridge

Figure: Pen and ink, arched top. Inscribed lower left corner: "Genevieve."

Monogram and date inscribed lower right: "August 1848." Two full-length

figures near a statue of a praying knight and his hound. On the left, a

young man seated before the statue plays a lute, gazing downward, while

a young woman faces him, leaning her right side against the back of the

statue's base while she listens to his song.

hand, and gazes with a rapt ascetic look at

the room before her, where, as if visible to her eyes, a child-angel is tending

a tall white lily. Beneath the pot in which the lily grows are six large books

in heavy bindings, bearing the names of the six cardinal virtues. These, and a

white dove perching on the trellis, are amongst the peaceful symbols of the

picture, whilst the tragedy also is foreshadowed in a figure of the cross formed

by the young vine-tendrils and in some strips of palm and “seven-thorned

briar” laid across the floor. Each of the figures, and the dove,

bears a halo, the name being inscribed within it. Rossetti painted the calm face

of his mother for St. Anna, and his sister Christina for the Virgin, giving her,

however, in contravention of the rule mentioned above, golden instead of dark

brown hair. The picture was signed with his name in full and the letters P.R.B.

after it, and the frame bore as legend two sonnets, of which the first, the

well-known one beginning

- “This is that blessed Mary, pre-elect

- God's Virgin.”

was printed in the catalogue. The sestet which follows is explanatory of

the picture:

- “So held she through her girlhood, as it were

- An angel-watered lily that near God

- Grows and is quiet; till, one dawn at home,

- She woke in her white bed, and had no fear

- At all,—yet wept till sunshine and felt awed,

- Because the fulness of her time was come.”

Coincidently with the

picture of

Mary's girlhood

, Rossetti began and finished the oil

portrait of his father, which is

reproduced on page 1. He also drew, one night in 1848,

sitting up till six in the morning to finish it, an exquisite

outline design of a lute-player and

his lady, from Coleridge's “Genevieve.” This was given to his friend, Coventry Patmore, who many years later

exchanged it for some studies by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. On the death of the

latter it was presented by Lady Burne-Jones to Mr. Fairfax Murray, in whose

possession it remains. Other interesting drawings of about this date exist,

among which may be mentioned a curious one done in

pen and ink on green paper as an illustration to Edgar

Allan Poe's “Ulalume.” This, which I have not seen mentioned or catalogued before, was sold

at Foster's in 1888, under the somewhat misleading title of “Welcome,” an auctioneer's blunder for the real name, which is

written on the drawing. Mr. Fairfax Murray

bought, and is the owner of this rarity, as

well as of another

design for “The Raven.”

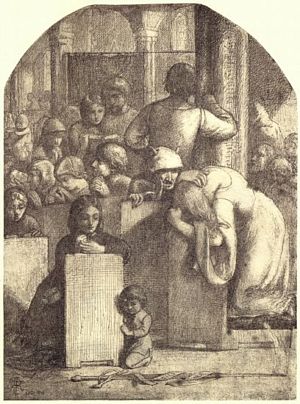

Two or three other pen-and-ink drawings of 1848 belong to Mr. J. A. R. Munro,

having been originally given to Rossetti's friend, Alex. Munro, the sculptor.

They include

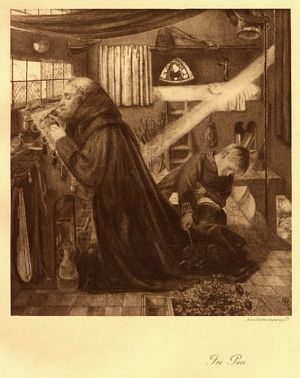

Gretchen in the Chapel

, with Mephistopheles whispering in her ear, and

The Sun may shine and we be cold

, a sketch of a girl with clasped hands, crouching in the embrasure of a

window, apparently a prisoner. Both of these were exhibited in 1883 at the

Burlington Fine Arts Club.

Although 1848 is intrinsically the year of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, much of

the work of the next two years comes within the scope of its influence. As an

example may be given here the

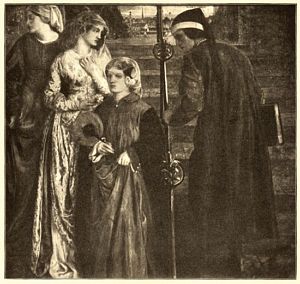

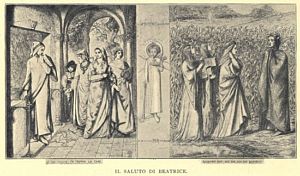

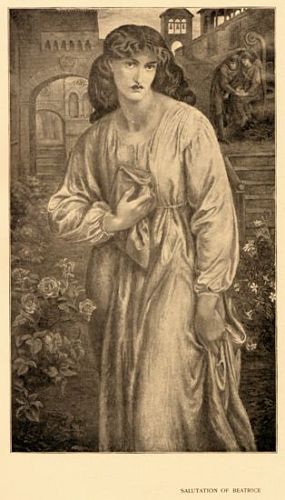

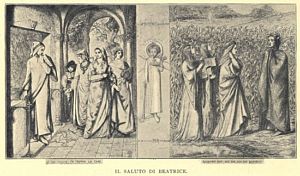

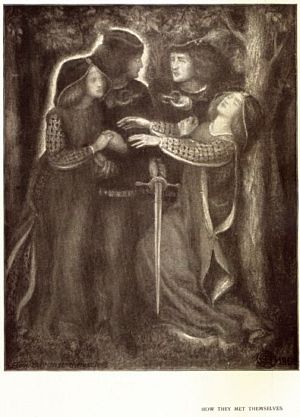

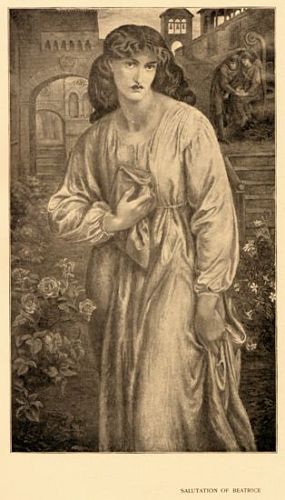

Il Saluto di Beatrice

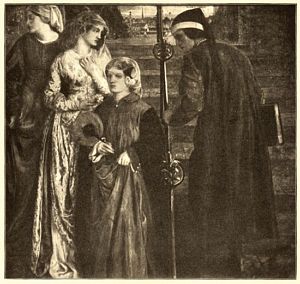

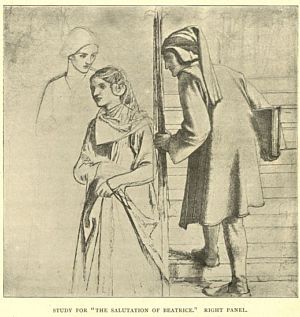

Figure: Pen and ink, three compartments. Text in left compartment: E cui

saluta fa tremar lo core D.G.R. 1850. Text in center compartment: 9

Guigno 1290 Ita n'e Beatrice in alto ciel Ed ha lasciato Amor meco

dolente. Text in right compartment: Guardami ben; ben son, ben son

Beatrice D.G.R. 1850. A full-length Dantis Amor stands in the central

compartment, holding a sundial and a down-turned torch. In the left

compartment, Beatrice and two women pass through a portico, to the right

of Dante and his servant. Beatrice and Dante look at one another. In the

right compartment, Beatrice followed by two women meets Dante before a

field of lilies. The women approach from the left and appear in profile,

Dante faces 3/4 front towards Beatrice. An angel is seen in the

distance.

important pen-and-ink drawing called

Il Saluto di Beatrice

, representing in two compartments the meeting of Dante and Beatrice,

first in a street of Florence and secondly in Paradise. The left compartment

(from the spectator's point of view) is dated 1849, and bears the legend from

the “Vita Nuova”—

E cui saluta fa tremar lo core. It represents Dante standing in the doorway of a cloister or portico,

overcome by the sweetness of the salutation given him by his lady, who is

passing with her arms linked in those of two girl-friends. In the background is

a statue of a mænad with cymbals. At the feet of Dante is a slab carved with the

outline of a mounted knight. In his hand the poet bears a volume of Virgil, and

through the half-open doorway is caught a glimpse of frescoed walls. The second

compartment is dated 1850, and shows Dante crowned with

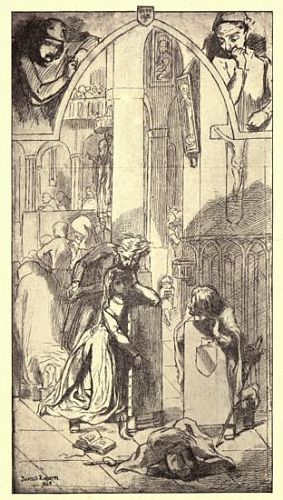

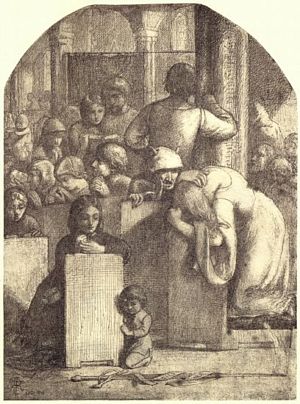

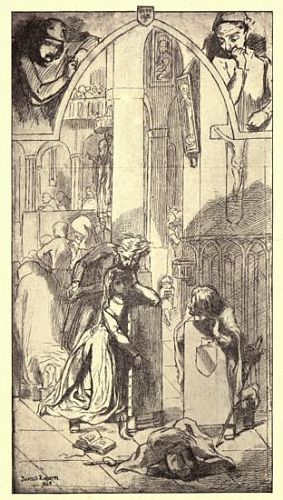

Gretchen and Mephistopheles in the Chapel. Two Designs

Figure: Pen and ink, rounded upper corners. Text in lower left corner:

G.C.D.R. July 1848. Numerous background figures pray in church pews. In

the foreground, a young woman facing forward kneels behind a short dias,

her eyes closed in prayer. A child kneels the right of the dais, and a

sword wrapped in a banner lies before them both. To the right behind

this pair, a devil with horns crouches behind another dais, over which a

woman leans, her hair unbound and her face concealed.

Figure: Pen and ink. Text in lower left corner: Dante G. Rossetti 1848.

Numerous background figures in church pews pray facing backward, while

in the foreground a young woman slouches over a small dais, and a man

with horns stands behind her, bending down towards her ear. To the

right, a second man kneeling behind another dais leans forward, looking

at the woman. The scene is enclosed within an arched architectural

frame, on the outside of which two half-length male figures watch the

scene, one in each of the upper corners.

laurel advancing to meet the forms of Beatrice and her two maidens

in the garden of Paradise. The latter are carrying instruments of music. Behind

the group is a field of swaying lilies, and in the distance a flying angel is

seen. Between the two compartments is a winged figure of Love, with bow and

quiver slung behind his back and a down-turned torch in his hand. Above this

figure is inscribed: “

Ita n' è

BEATRICE in alto

cielo

;” and below: “